But when them red lights came on in the recording studio, it was like a bell ringing in a boxing match and I did it.” Eleventh grader Robert Upton’s eyes grow as if those red lights line the back wall of Kenwood Academy’s drama classroom. “I reached down inside of me, and I pulled out whatever was there. I did my best, and I figure nobody can fault me for that.” As Floyd from August Wilson’s “Seven Guitars,” Upton begs the invisible Vera for another shot. “Try me one more time, and I will never jump back on you in life.”

Robert and two other Kenwood students have a week to prepare for the Chicago Regional Finals of the August Wilson Monologue Competition. On March 10, twenty students from all across the city will compete at the Goodman Theatre for three places in the National Finals in New York. Cree Rankin of Court Theatre, who sits in front of Upton carefully coaching him, has facilitated the program at South Side schools since Chicago first entered the competition three years ago. This year, students from Harper High School, Simeon Career Academy, Sullivan House Alternative School, and Kenwood Academy were among the 390 to prepare monologues and compete, but only three Kenwood students have made it to the final round. No student from the South Side has ever made it to the New York finals.

Upton is having a rough rehearsal, asking for a lot of breaks. Rankin lets the eleventh grader take the time he needs, but forces him to stay focused. In addition to serving as Court’s Casting Director, Rankin is also in charge of the theater’s Artists-in-the-Schools program. He coordinates a cadre of teaching artists who work with each participating student to prepare a two or three-minute monologue from August Wilson’s “Century Cycle.” Also known as the “Pittsburgh Cycle,” after the city where most of the action is set, the ten plays each take place in a different decade, and are intended to tell the story of the African-American experience over the course of the twentieth century.

The monologues present snapshots of Wilson’s complex yet archetypal characters. Wilson’s female characters speak of the challenging men that they can’t stop loving, of their regret or refusal to have children for fear of violent realities. His male characters beg their women to believe in them, and deliberate on what they have to do to believe in themselves, to support their families, and to survive.

“Floyd may be fighting for the words, but he’s not fighting for the inspiration,” Rankin explains to Upton. “He’s still coming from that point of strength. Something about robbing a bank, and getting away with it…”

When asked if he’s ever felt that kind of power, Upton dramatically raises his hand to his chin to think. “I think when I was thirteen and getting a girl’s number. That made me feel powerful. I was like, ‘Yup I can do it…I did it.’”

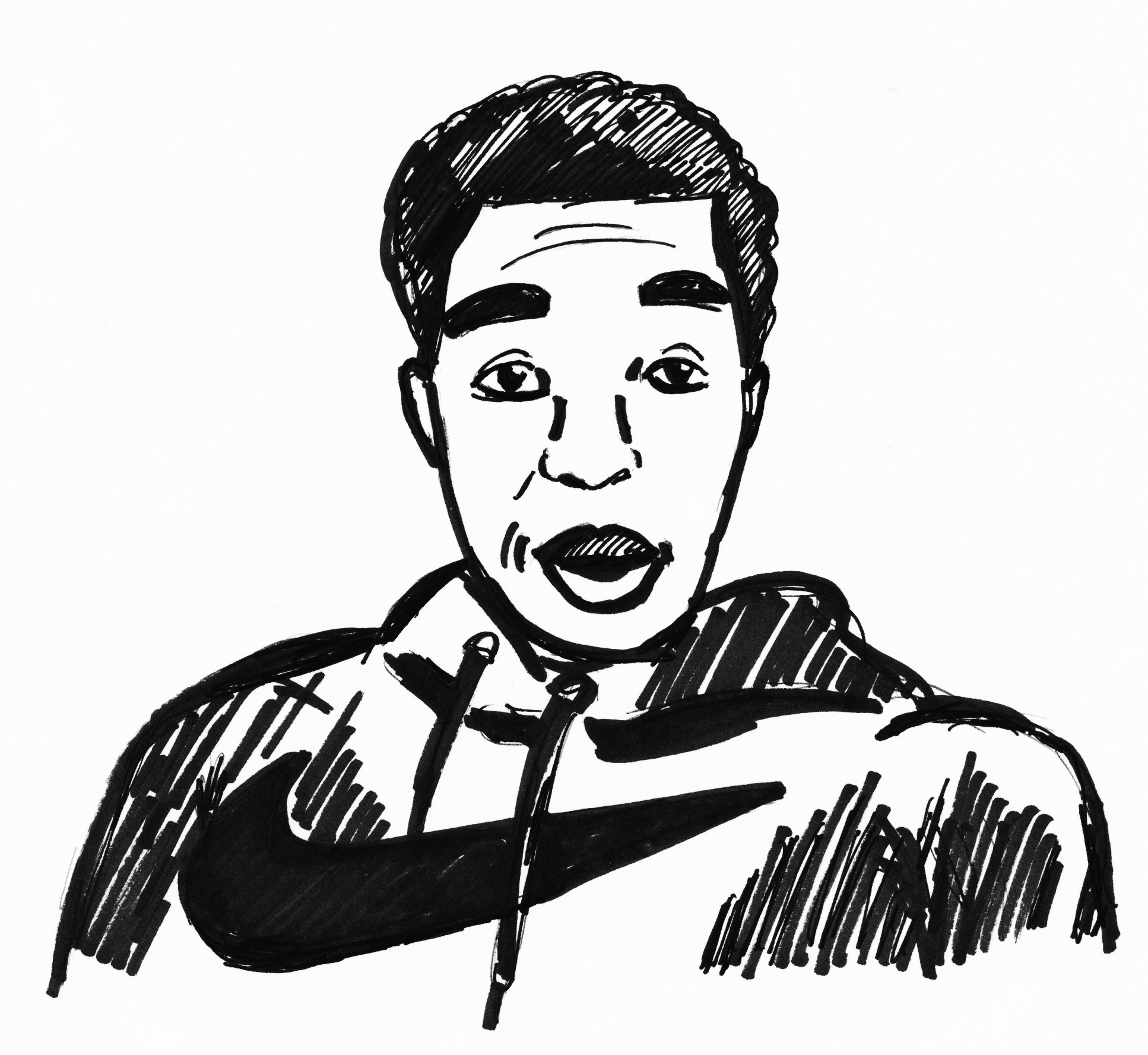

When Sejahari Saulter-Villegas arrives at the Court Theatre to practice with Rankin on a Saturday afternoon, the Kenwood freshman is all smiles and has a seemingly permanent bounce in his step. His Nike sweatpants are tucked into the bottom half of cut-off jeans, a fashion innovation of his own.

Saulter-Villegas sinks into a chair to begin King’s monologue from “King Hadley II,” and his bright eyes fade as he falls into a character that Rankin describes as a “cocktail of desperation.” An ex-convict in Pittsburgh, King is black, poor, and uneducated.

“My fifth grade teacher told me I was gonna be a good janitor, say, she could tell by how good I erased the blackboard.”

It doesn’t take long to realize that Saulter-Villegas is not new to the stage; his poetic cadence and controlled choreography creep into his execution of this monologue. His mother founded and runs a hip-hop arts organization, called Kuumba Lynx, and Saulter-Villegas is an active participant in the group’s performances. Of performance he says, “I was raised in that.” Last year, his team won Louder Than a Bomb, the annual Chicago slam poetry competition. This year he will compete in the semifinals again, a day before the final round of the August Wilson Competition.

“I know which way the wind is blowing. And it ain’t blowin my way,” he concludes. After taking a moment for the wind to take this last line, he bows slightly, and when his head comes up his dimples return.

Though Saulter-Villegas seems an old hand at performance, he is one of 180 Kenwood students in six drama classes who studied and performed these monologues. At Kenwood, the monologues are incorporated into the curriculum by drama teachers Mr. Nemeth and Ms. Bolos. Students study in depth the plays from which their monologues are chosen before Rankin and other actors come in to work with them one-on-one. The students also attend plays at Court as part of their course of study.

“Kids come back to visit you, and they don’t remember the play you taught them or the activity they did in class, but they remember being taken to plays,” said Nemeth. “Kids are never going to experience this…if they don’t have the chance to, and I would say that, for the most part, over my twenty-five years of teaching, kids typically rise to the occasion.”

This year posed a new difficulty for the program at Kenwood. The Chicago Public Schools instated a new policy that includes drama as a way to fulfill the high school arts requirement. This meant that the same allotments of time, money, and resources had to stretch to cover twice the previous number of students at Kenwood. “We cut our coaching time in half,” Rankin says. Expanding the program also meant that more students were taking the drama class simply to fill the district’s requirement, not necessarily because they wanted to learn about theater. When a student hasn’t learned their lines, for example, “you can’t just say ‘I’m sorry I’m not gonna work with you today,’ because it’s an academic class and there are requirements that go with it,” Rankin said.

It also means, however, that freshmen and sophomores, like Saulter-Villegas and Kenwood’s third finalist, Kenneth Hastings, can participate in the theater program earlier on in their high school careers.

“Once they start learning these monologues and feeling successful about presenting them,” Nemeth says, “that’s where, I think, that motivation develops.” But he admits this isn’t always the case. “Like Robert, he just wants to win the contest.”

On the night of the Regional Finals, Rankin navigates the lobby of the Goodman Theatre in the same way that he navigates the halls of Kenwood Academy. Clad in his White Sox cap, he knows as many professional actors at the Goodman as he does students at Kenwood, greeting each with a compliment or a joke at his or her expense.

Accompanying him is Patrese McClain, the lead teaching artist at Harper High School. When working with the Kenwood students before the competition, she led the boys through warm-up exercises with an infectious energy. McClain—a native of the South Side—is passionate, she says, about working in the “schools that face the most challenges.”

“I’m really excited to be able to give these kids exposure to August Wilson, to professional theater, things that are not really an everyday occurrence on the South Side.” She says that when coaching the finalists, she focuses on basics of performing, of starting from a neutral stance, of breath support. But also, she says, “At this point, we’re nurturing young artists…giving them tools for life…and being a positive influence on what they choose for their life.”

McClain attended St. Francis de Sales High School and went on to study theater at Penn State and Howard University. “When I was growing up, I did not have any professional connections, I was just a kid who was dramatic.” She thinks it unfair that students from arts schools like Chicago High School for the Arts (ChiArts), where drama students train extensively, compete with those whose schools may not have the same resources to put toward the program.

Both Rankin and McClain have disagreed with the judges’ decisions in past years. They point out a young man walking around the lobby, a 2013 graduate of Kenwood who they think should have been a finalist in last year’s competition. His name is Barton Fitzpatrick, and in addition to being Upton’s uncle, he’s now a freshman studying theater at the University of Illinois-Chicago. “I used to play basketball actually, but after being involved in the competition, I took up acting. So I guess you could say that the competition has changed my life.”

“If I could speak to the contestants going into the competition, I would tell them not to go into the competition expecting anything,” he says. He worked with his nephew on his monologue and was excited to see how it turned out. When Fitzpatrick’s sister, Upton’s mother, walks in, she passes Rankin to ask, “Are you as nervous as we are?”

Presented en masse by the twenty finalists, the stories of Wilson’s characters weave together, demonstrating that they are all part of a single history, a community whose common, private difficulties form a shared, public experience in Wilson’s words. Indeed, all of these students have worked tirelessly to tell these stories. However cohesive this narrative, though, after the last performance Master of Ceremonies and competition organizer Derrick Sanders calls all of the students to the stage to announce the three winners. The winners receive cash prizes and a spot in the New York competition. The first place winner will receive a scholarship to UIC.

In third place is a ChiArts student, Shea Glover. Applause.

Second place: Robert Upton.

Rankin jumps from his seat, as do the twenty Kenwood students who took a school bus to the theater with Mr. Nemeth. They comprise the loudest contingent in the audience and spend the bus ride back to Hyde Park in celebration.

When asked for her reaction to her son’s win, Gloria Upton had to take a second to think. “What’s a big word that means super excited?” Then she expanded. “I’m just happy that we get a chance to look at a young, black man in Chicago that’s doing something positive.”

Upton accredited his confidence on stage to seeing both of his parents, who are not together, in the audience cheering for him. “Seeing them both there made me proud.”

In early May, Upton (and first place winner Candace Spates of Lincoln Park High School) will compete in the Finals Round in New York City. It will be Rankin’s first time coaching a finalist in the competition.