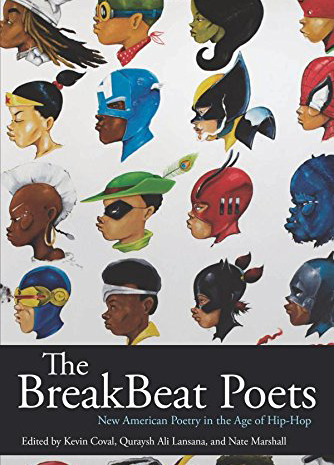

The Breakbeat Poets bills itself as an anthology “by and for the Hip-Hop generation.” In some poems hip-hop is the central object of meditation, while in others its beat pulses unobtrusively in the background. But its influence is inescapable. Hip-hop’s rhythm is in the meter, and its language is in the diction. Prominent Chicago emcee Chance the Rapper has gone so far as to call The Breakbeat Poets, edited by Kevin Coval, Nate Marshall, and Quraysh Ali Lansana and published by Haymarket Books, “a cool & diversified version of a mixtape.”

And diversified it is. Though the anthology’s hip-hop influence is especially evident, it also intersects with the cultures of slam poetry, academia, spoken word, and social justice activism. The published poets are variously rappers, professors, playwrights, and high school students, all arranged by year of birth, from 1961 to 1999. Coval asserts in his introduction, “There are established and highly decorated poets with several publications and there are poets whose first time appearing in print is this collection. All dope and equally relevant.”

Yet there can be no doubt that the older poets carry the anthology, and the best poems mostly reside in its first half. Their experience is evident both in technique and thematic weight. Lansana is himself a clear frontrunner, depicting life in a crack house in vivid sensory detail: “parched bones / silently akimbo / peel of burn / gray of skin / he sizzles / cooks.” LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs, another exceptional talent, specializes in boisterous absurdity. Her most successful poem, “who you callin’ a jynx?”, borrows Japanese cultural images and vocabulary in a characteristically American statement of defiance.

The older poets are also some of the most daring when it comes to form. Roger Bonair-Agard’s “Honorific or black boy to black boy” presents a word cloud of oft-heard greetings, with no evident beginning or end, while his manic, rambling, prose-poem “Fast—how I knew” explores youth through the lens of Muhammad Ali, blurring the distinction between poetry and storytelling.

Still, not all such experiments are as well executed. Douglas Kearney’s “Quantum Spit” employs a cacophony of varying fonts, sizes, overlapping lines, tilted phrases, and odd punctuation. While there may be something to be said for the poem’s sense of disorientation, it creates confusion rather than meaningful uncertainty.

In the work of the younger poets, hip-hop’s influence is felt more directly; rather than borrowing theme or style, songs, artists, and lyrics are referenced by name. Borrowing so explicitly is risky; it’s all too easy to coast on the many strong ideas and images already established by hip-hop. The very best work filters these ideas and images through fresh perspective.

The younger poets are also more political. Almost all the work in the anthology is at least implicitly political, but the younger slam-influenced poets are especially unafraid to say what they mean. At worst, things can get a bit facile; “I Have a Drone” is dedicated to “Barack-George-W-Bush-Obama.” But the activist zeal yields some of the anthology’s most powerful images, as in Camonghne Felix’s “Police”: “my word pales cocktail pink against his.” And Sarah Blake’s “Adventures,” the collection’s most memorable political poem, examines Hurricane Katrina through the eyes of Kanye West. The connection to hip-hop is direct without being derivative, while the political slant is explicit without sacrificing depth.

Outside of the poems themselves, The Breakbeat Poets consists of Kevin Coval’s lengthy introduction as well as a collection of short essays. Regrettably, the framing material doesn’t quite live up to the poems. Coval’s obvious disdain for the mainstream poetic tradition (“dead white dudes who got lost in the forest”) is a bit brash, given that many of the featured poets engage with this tradition and try to reconcile its problematic racial foundations with its artistic value. The essays are generally sincere, straightforward appreciations of hip-hop, but they don’t have much to say that wasn’t already covered by the poetry itself, the one exception being Patrick Rosal’s outstanding essay on dance and accident, an examination of the spontaneous emergence of meaning from chaos. In this sense, it’s a rather apt metaphor for hip-hop, a renaissance of beauty and expression emerging from oppression and disenfranchisement. Though their styles, influences, and backgrounds diverge, the Breakbeat Poets are bound together by this shared hip-hop ethos, even as they filter it through a new medium.