Divvy—North America’s largest bike-sharing service by number of stations and coverage area—operates 476 stations in Chicago. Since 2013, the stations have been a characteristic feature across the city, their rows of gleaming blue bikes marking street corners across the Loop and the North Side. For the last two years, Divvy has been moving to expand service to neighborhoods farther from downtown, particularly areas with less foot traffic on the South and Northwest Sides. This summer, Divvy plans to add at least forty stations in Englewood, Burnside, Chatham, Greater Grand Crossing, and Brighton Park. Although this investment is encouraging, an analysis of ridership data suggests that Divvy may need many more expansions on the South Side to replicate its successes in Lincoln Park, Lakeview, Uptown, and the Near North Side, where there is a much denser, more established network of Divvy stations.

Over the final three months of 2015—the most recent dates for which Divvy has released ridership data—the most used Divvy station in the city was Station #91, located on the Near West Side, with 9501 total rides, more than a hundred each day. Station #91 is located at the corner of Clinton and Washington, centrally located in the city, where it can capture a diverse array of traffic: commuters heading to office buildings in the Loop, workers heading home to apartments west on Ashland Avenue, and suburban visitors arriving at the Ogilvie Transportation Center on their way into the city. Although Station #91 is unusually successful, there were hundreds of stations boasting thousands of riders during the fourth quarter of 2015—the most successful of them concentrated in a small area of downtown Chicago.

That’s one side of Divvy. On the other hand, there are stations #384, #386, and #388, added during Divvy’s expansion last spring into previously unserved parts of the South Side. These three stations, all situated along Halsted Avenue in Back of the Yards and Englewood in a much less central and densely populated area than Station #91, collectively boasted over the same three months exactly twenty riders. They are, like Station #91, extreme examples, but not unusual. The average Divvy station in Englewood boasted seventeen riders, an average of one every five days or so. These numbers are very low not merely in comparison with the far denser and more tourist-inundated neighborhoods surrounding downtown but also in comparison with largely residential neighborhoods along the farther reaches of the North, Northwest, and West Sides: neighborhoods like Irving Park, Rogers Park, Avondale, and Logan Square, where Divvy also just recently arrived.

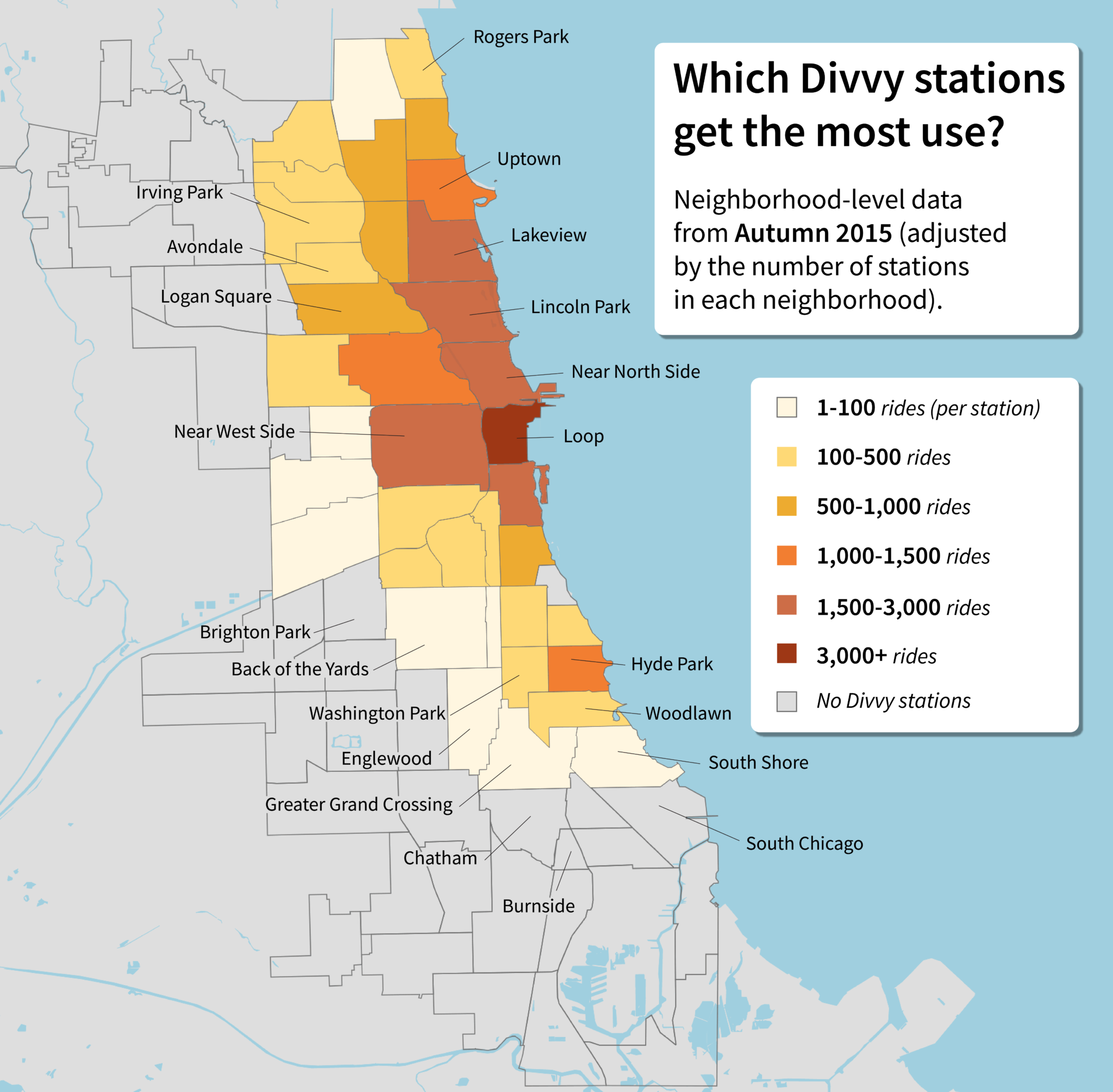

Divvy is currently much more of an established presence on the North Side than the South Side: its expansion into most of its coverage area on the South Side is scarcely a year old, and entire neighborhoods, particularly on the Far South Side and the Southwest Side, still lack a single station. More than seventy percent of Divvy’s ridership comes from the Near North Side, the Loop, the Near West Side, Lincoln Park, and Lakeview, where a little under half of its stations are located, even though these five neighborhoods comprise only about twelve percent of Chicago’s population. On the other hand, the enormous geographic space of the entire South Side—occupying just over half of the total area of the City of Chicago—accounts for only about a fifth of Divvy’s stations and less than one-twentieth of its total ridership. If Hyde Park is excluded, the latter number goes down to 2.7 percent. The South Side is underserved in terms of Divvy stations, and those stations are underused in terms of the number of riders per station—factors that might be directly related to each other, given the way in which Divvy riders likely take advantage of a dense network of stations to travel short distances.

Considering that Divvy aims to be an affordable, citywide service and expand into a vast and underserved portion of the city, the expansion makes a lot of sense: Burnside, Chatham, and Brighton Park are not at all served by Divvy as it currently stands, while Greater Grand Crossing and Englewood boast only seven stations to service a population of almost sixty-five thousand. According to Mike Claffey, the Director of Public Affairs for the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT), “We are continuing to push out the network in all directions as funding for new stations and bikes becomes available,” in order to achieve Divvy’s goal of “a citywide bike share program.” As it currently stands, hundreds of thousands of residents on the South Side live outside of Divvy’s coverage area and tens of thousands more live in neighborhoods with only a few stations. In order for Divvy to function at a citywide level, it will need to vastly expand its coverage on the South Side. The question then, remains: what are the factors motivating Divvy ridership? And what can the city do to successfully market the service to those regions that currently have low ridership?

Hyde Park ridership presents one of the most encouraging examples for Divvy expansion on the South Side. Divvy has more per-capita usage in Hyde Park than in Uptown or Logan Square—neighborhoods that are both substantially more densely populated and closer to downtown—and Hyde Park may soon surpass West Town, the bustling West Side neighborhood that contains Wicker Park. The busiest Divvy station on the South Side is #423 in Hyde Park, opposite the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library on 57th Street. Moreover, ridership in Hyde Park is increasing—between the second and fourth quarter of 2015 it increased by more than ten percent—while ridership across the city decreased by about thirty percent (probably due to a seasonal decrease in ridership during the winter months). The popularity of Divvy in Hyde Park has even increased ridership in neighboring Woodlawn and Washington Park: about sixty percent of rides beginning in those neighborhoods end in Hyde Park, and stations in these neighborhoods have been substantially busier than stations in many other South Side neighborhoods. Hyde Park, then, may suggest that Divvy can catch on in the South Side, if given a bit of time and a denser network of stations: Hyde Park has thirteen stations, whereas Englewood, which is almost twice as large geographically, has only four.

But if the numbers in Hyde Park are an encouraging development for Divvy, the numbers in the neighborhoods surrounding Hyde Park suggest otherwise. Over the last quarter, Woodlawn and South Shore have seen much lower ridership than Hyde Park. One possible factor may be the density of bike lanes: bike lane maps provided by the City of Chicago show that the network of bike lanes is far denser in Hyde Park than in surrounding neighborhoods on the South Side. Woodlawn and South Shore are both about as densely populated as Hyde Park but lack the presence of the UofC and the bike lanes and other cyclist-friendly infrastructure of the neighborhood.

The results from Woodlawn and South Shore are counterexamples to Divvy’s success in Hyde Park, but they should be taken with a bit of caution, too—Divvy’s network is less dense in these neighborhoods, and far less dense or nonexistent in the neighborhoods to the west and south of Woodlawn and South Shore. It may be that Divvy’s middling numbers in Woodlawn and South Shore could be remedied with more stations in neighboring South Chicago and Washington Park and more bike lanes throughout.

In addition to increasing service coverage on the South Side, Divvy might be able to increase ridership and become an “affordable transportation option everywhere that it reaches,” according to Claffey, by further marketing their Divvy for Everyone (D4E) program. In order to address financial barriers and increase access to Divvy, CDOT offers a one-year membership for a one-time fee of five dollars to first time riders making under three hundred percent of the federal poverty level—about 60 percent higher than the Chicago minimum wage for a single person, and up to $72,750 for a family of four. And unlike the other Divvy membership options, riders can sign up in person without a credit or debit card. A huge portion of Chicago, in fact, is eligible for the D4E program: around forty-five percent of the city makes under two hundred percent of the federal poverty line, so the three-hundred-percent cutoff could almost certainly capture a majority of the city’s residents. Only “about eleven hundred people have signed up through D4E,” according to Claffey, however, which may suggest vast untapped potential for limited-income Divvy riders, who could be unaware that they are eligible for the program.

Divvy aims to be a program that serves the entire city of Chicago, but it is currently far from doing so, particularly on the South Side, where large stretches are either outside of Divvy’s coverage area or unserved by the system. Divvy’s proposed expansion may do a great deal to change this disparity, particularly if combined with further outreach to a greater number of limited-income residents through the D4E program. Currently Divvy is a nonentity for hundreds of thousands of Chicago residents across the South Side who are outside its coverage area and or in underserved Divvy neighborhoods such as Englewood, Greater Grand Crossing, and Back of the Yards. This summer’s expansion may be able to bring more of those residents into the program, but it is likely that many more expansions will be needed to create a dense network of Divvy stations on the South Side and make Divvy a viable transportation alternative.

[jsfiddle url=”https://jsfiddle.net/jeancochrane/kqjk2ww2/” height=”500px” include=”result,html,js,css”]