In February, the Hyde Park Herald reported that 4th Ward Alderman Sophia King had floated the idea of forming a community land trust in Bronzeville. Created in partnership with GN Bank, the land trust would provide a way for nonprofits to cheaply acquire and develop vacant lots in Bronzeville. “We’re not [averse] to developers developing, but we want to make sure that money stays in the community first and we harness the equity that’s in the land,” she said. (When reached for comment, King’s office said the proposal is still in its early stages.)

In her losing campaign for the 20th Ward aldermanic office, Nicole Johnson also suggested the creation of a community land trust, intended to combat displacement as Woodlawn feels the effects of Obama Center–related investment and speculation. And the newly elected 25th Ward Alderman, Byron Sigcho-Lopez, is the former executive director of Pilsen Alliance, a neighborhood organization that has advocated for community land trusts as part of its affordable housing plan.

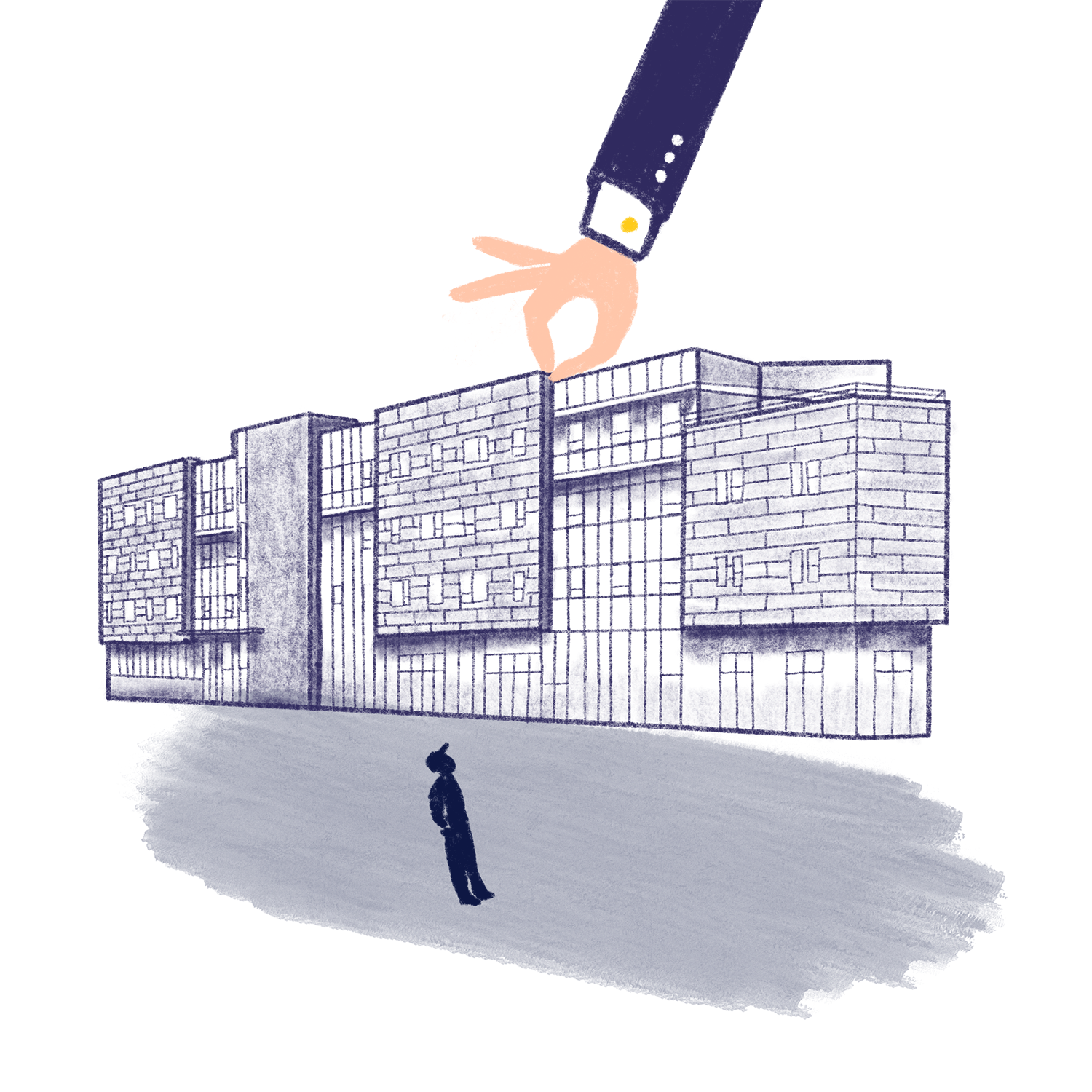

All of which is to say, community land trusts—nonprofits that buy land and lease it out to low-income homeowners—are, at least rhetorically, increasingly popular among politicians eager to signal their commitment to fighting for affordability in the face of rapid neighborhood change.

The last few decades have seen the formation of several community land trusts (CLTs) in and around Chicago, including the controversial citywide Chicago Community Land Trust. However, there are currently no CLTs focused solely on the South Side. That will soon change: over the next couple months, a group of nonprofits and community organizations will begin acquiring property in Chicago Lawn and, later, Woodlawn, taking over vacant and foreclosed homes and leasing them to community members. Over time, they hope to expand to four or so neighborhoods in total, with about fifty homes in each area.

Community land trusts have a long and complicated history, stretching back through the urban crisis of the second half of the twentieth century, the Civil Rights Movement, and back-to-the-land optimism. It’s been a contentious evolution, one that some critics argue has resulted in a kind of institutionalized toothlessness. What started as a radical and democratic movement has given way to an affordable housing policy tool that, for all its benefits, fails to truly empower Black and brown communities.

This new land trust was formed in part by progressive housing organizers who rose to prominence for their militant activism in the wake of the foreclosure crisis. Whether it can restore the concept to its roots remains to be seen.

The new Chicago initiative’s lead organization is the Chicago Community Loan Fund (CCLF), a nonprofit lender that has been around since 1991. “The land trust is trying to accomplish a couple of things. As property values do increase in neighborhoods, we’re trying to maintain economic diversity, and trying to promote homeownership,” said Bob Tucker, the CCLF’s chief operating officer.

In one sense, then, the land trust is intended as a preemptive strike against the displacement that can follow gentrification. But it’s also part of the ongoing attempt to clean up after the housing crisis. Between 2007 and 2012, for instance, Chicago Lawn saw more than 500 foreclosure filings each year, according to the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul. And many of those buildings are still vacant, often because mortgage lenders hold them in a kind of administrative limbo, refusing to claim “official ownership.” Within the neighborhood, the land trust is one part of an ongoing effort by a number of Southwest Side community organizations to rehabilitate and restore those properties. (The project is also tied to the foreclosure crisis in another sense: some of the land trust’s initial funding came from Bank of America, money from its $17 billion settlement with the Department of Justice over the sale of bundles of risky mortgages to investors.)

The CCLF is working with the Greater Southwest Development Corporation (GSDC), as well as Action Now and the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign, all community organizations or nonprofits that work on housing and development on the South Side. “Because there’s so much available, there’s already investors buying properties who want to flip them,” said Christine James, the director of operations at the GSDC. “How can we think about displaced families and what would actually work in a rapidly changing neighborhood?”

The trust will acquire the property from a couple of different places—some of it will come from the city, while other lots will be bought on the private market. Tucker also mentioned that they’ve been working with the Cook County Land Bank Authority, which owns dozens of properties, most of it vacant land, in West Woodlawn. Once the CLT owns the land, it will lease it out to local residents looking to buy a house. (Not all of those people will necessarily be renters; some might be looking to downsize to smaller and more manageable houses.)

Tucker says that the land trust will be “real sensitive to the neighborhoods” it’s in. To that end, Woodlawn and Chicago Lawn, and any other new area the land trust expands into, will have their own community advisory boards, composed of residents from the area, that will offer guidance on outreach, expansion, and other issues pertaining to the neighborhood.

Attempts at communal ownership of land, usually animated by utopian hopes, have existed for centuries, but historians locate the roots of the community land trust in Southwest Georgia in 1968. There, activists affiliated with the civil rights movement’s Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—after taking a trip to Israel to study kibbutzes, the collective farms first organized by Labor Zionists—started New Communities, Inc on 5,700 acres of farm- and woodland. There, they raised cattle, and grew corn, peanuts, and soybeans.

Charles Sherrod, one of the founders, argued at the time that the land trust would give Black people a way to fight back against the terror of everyday life in the South. “Land is the source of power, the source of all power. It’s the source of life. And with land a man holds in his hand the mechanism to control his destiny,” he said. “If a people is going to rise, it must have land.”

New Communities broke up after sixteen years, undone by drought and debt. (In 1999, the land trust was part of a successful class-action lawsuit alleging that the Department of Agriculture’s failure to provide proper loan assistance to thousands of Black farmers reflected racial bias at the agency.) In the early seventies, however, some of the people affiliated with New Communities wrote a book in which they coined the phrase “community land trust,” and described how the Southwest Georgia experiment provided a model for community-controlled development.

“The community land trust is not primarily concerned with common ownership,” they write. “Rather, its concern is for ownership for the common good, which may or may not be combined with common ownership.” The book goes on to sketch a vision of property that’s essentially decommodified, removed from the market through long-term leases with heavy restrictions.

Importantly, the authors also emphasize that the idea of community—“an overused, imprecise, and confusing word”—extends not just to residents living on the land, but also to others near the land, or those who have some vested interest in it. In the case of New Communities, that included local civil rights organizations tied to the land trust, businesses that bought from the trust, and Georgians living in the surrounding counties. In a broader sense, the authors add, the community encompasses “the community of all mankind.”

Concretely, this meant that CLT advocates suggested the formation of a tripartite structure within any individual land trust’s board of directors, one that would represent three distinct groups: leaseholders, residents of the land trust’s service area who didn’t live on the land, and the general public. There were other characteristics sketched out too—the land trust was to be a nonprofit open to anyone living in the area it covered, and the board of directors should be democratically elected by CLT members.

In the late seventies, a couple of community land trusts—one in Tennessee, another in Maine—formed along the lines of this model. Like New Communities, both were rural; it wasn’t until 1980 that the first urban community land trust was established in Cincinnati. When it formed, the organizers behind it realized that the model created a decade earlier needed some adjustments to work in a city. In particular, activists in Cincinnati emphasized the need for land trusts that maintained affordable housing and helped disadvantaged, low-income people beyond simply providing them with cheap access to land. “In the vocabulary of the liberation theology of that period, there should be a ‘preferential option for the poor,’” writes historian and CLT advocate John Emmeus Davis.

Throughout the rest of the 1980s, other urban land trusts formed, some of which still exist today. Much-lauded success stories include Dudley Neighbors, Inc in Boston, and the Champlain Housing Trust in Burlington, Vermont. A few decades later, after the onset of the housing crisis, land trusts—which, remember, primarily exist in low-income communities—gained attention because they were about eight times less likely to be in foreclosure than all other mortgage types combined. (That stat is obviously slightly skewed, since it includes subprime loans, but land trusts still went into foreclosure about seven times less often than loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration.) That finding sparked even more investment from large-scale philanthropic groups, like the Ford Foundation that had already taken an interest in CLTs. A 2016 report from the Center for American Progress estimated there are about 220 community land trusts in the United States.

But during that time, some people have also noted a shift in the way land trusts have been employed, away from their beginnings as radically democratic community organizations. In a 2018 academic paper, James DeFilippis, Brian Stromberg, and Olivia R. Williams argue that the CLT has become a “tool for policy elites looking to create a subsidy-efficient stock of individualistic, owner-occupied homes.” In interviews with CLT executives, and through examinations of board statements, the authors note that the focus of most CLTs now seems to be on providing affordable housing, as opposed to creating a community of people in a neighborhood or city. “I’m not drinking the Kool-Aid, you can’t make me, I think you’re all nuts. That you’re taking the commune kind of approach to life. That’s not what we’re about. We’re about getting people into homeownership,” said the executive director of one land trust.

“There’s nothing radical about community, there’s no inherent political content in any kind of geographic scale of anything. The most durable expression of community control we have is rich white suburbs, [which] have spent last seventy-five years keeping Black and brown people out,” James DeFilippis, a Rutgers University urban planning professor, told the Weekly. “But if you’re talking about poor people and people of color, and at least working-class people, that is much more radical, because that’s not a set of people in a position to control much—full stop.”

But in today’s land trusts, Charles Sherrod’s bid for emancipation—the hope that a people’s ownership of land might allow it to “rise” and rebel against oppression—has in many cases been gutted of its most radical content.

One example DeFilippis and his co-authors cite disapprovingly is the Chicago Community Land Trust (CCLT), a city program created in 2006. The CCLT provides low-income homebuyers with subsidies and property tax reductions if they purchase a home through the trust, but, as DeFilippis’s paper describes it: “Its board consists entirely of members appointed by the mayor, and its meetings are held at City Hall. Though many community groups were initially involved in the creation of the CLT, there is not even a pretense of community control in its operations.” (The trust’s website notes that once the CCLT acquires 200 houses, a third of the board will consist of homeowners in the trust; at the moment, thirteen years since its inception, there are ninety-nine houses in its portfolio.)

A 2017 report from the Office of the Inspector General also found that the land trust was never given enough money from the city to fulfill its mission, and the city should either fully fund it or “sunset” the organization altogether. In response, The Department of Planning and Development promised that it would expand its operations and begin to fundraise more actively; it also said it would change the CCLT’s name, no longer classifying it as a “land trust”—a request the inspector general made because the organization does not actually acquire land.

A follow-up report from the inspector general, released this past February, praised the trust for hiring an executive director and making efforts to fundraise from outside philanthropic sources. But it also noted that it had failed to implement other recommendations, such as leasing deeds for ninety-nine years. (And in the end, DPD elected not to change the name of the land trust, “because its board was unable to find a name that correctly and adequately described CCLT activities and was sufficiently different from similar organizations in Chicago.”)

There have been other, more successful community land trusts in Chicago and the surrounding suburbs, though. The first CLT in the state was founded in 2003, in north suburban Highland Park. (Buzz Bissinger once described it as a place that “would look familiar to the creators of The Truman Show.”) Amy Kaufman, associate director of the nonprofit that runs the land trust, said the land trust was started as a way to provide housing for the “people who have lived there for decades…seniors, people who raised their families, policemen, firemen, teachers, people who work in schools and hospitals.” At the moment, it has about ninety properties in it. The Highland Park trust seems to have become something of a model for other land trusts; the CCLF’s Tucker, for instance, said it was a good example of what his organization had in mind.

It didn’t, however, manage to prevent Highland Park from finding itself on a December list of statewide communities required to submit affordable housing plans to the Illinois Housing Development Authority because less than ten percent of their housing stock is affordable—though, at 9.3 percent, it was the best of the forty-six towns named. Of course, it would be slightly unfair to blame the larger lack of affordable housing in a wealthy suburb on a land trust that only contains approximately ninety properties. But it does show that CLTs aren’t primarily designed to create affordable housing at larger scales, which may only make it more important to focus on preserving their radical potential.

Will the CCLF’s land trust do that? One possible reason for optimism is the participation of the Anti-Eviction Campaign. Earlier this decade, the organization came to prominence for its work to protect “the human right to housing,” including its takeover of vacant homes on the South Side, which it would fix up for people to squat and live in. “There’s a wealth of understanding about relationship to land and indigenous communities and how nomadic society has become,” said J.R. Fleming, the group’s co-founder. But on the South Side, there were no mechanisms to ensure people could remain in their neighborhoods—“communities were being uprooted.”

The Anti-Eviction Campaign’s interest in land trusts had its basis in the goal of creating more permanent housing for the vulnerable. But according to Fleming and Toussaint Losier, the other founder, it also emerged out of thinking about another problem they sometimes faced—how to ensure that neighbors were invested in the group’s work. “Something that was really important not only to our members, but also people who were neighbors who were asking questions, like, ‘What’s the neighborhood benefit of the work that you’re doing?’ ” said Losier.

Either way, Fleming said he hopes the land trust can involve other residents of the neighborhood. “Once the homes start selling, other board members will take position of homeowners, and [become part of the] decision-making body,” he said. “[We want to get people] invested in community to the degree where there is concern about the type of commercial development that is happening…. When you have people invested in community, you tend to have a good community.”

Christian Belanger is a senior editor at the Weekly. He last wrote about the 20th Ward election.