On December 6, 1928, an army regiment fired machine guns into a crowd of United Fruit Company workers on strike for a six-day workweek and an eight-hour workday in Santa Marta, Colombia. Somewhere between eight hundred and three thousand workers were murdered in cold blood. Jorge Franklin Cardenas, the cartoonist and painter whose work is currently on display at Uri-Eichen Gallery, was eighteen years old.

“That’s when he started off his life of being in the wrong place at the wrong time,” said Stephanie Franklin, Cardenas’s daughter-in-law, who compiled and curated the collection currently on display at the Pilsen gallery. As the grandson of a prominent family in the Santa Marta community, Cardenas was deeply affected by the cataclysmic culmination of the month-long labor strike. “It affected everyone at the time,” said Franklin. “Without that experience, he might not have encountered the need to fight for freedom.”

“Joe Hill 100 Years Part 4” is the fourth in a series of shows dedicated to the centennial anniversary of the unjust trial and execution of Joe Hill, an International Workers of the World organizer and the voice behind some of the most influential songs of the early twentieth-century labor movement. The show reflects on the legacy of the mythologized labor activist, honoring his death and the power of radical art. More than simple examples of political art, a series of paintings by James Wechsler and the Jorge Cardenas collection provide a commentary on history, remembrance, and the role of the radical.

The intensely personal and political work of radical artists like Joe Hill and Jorge Cardenas allows for historical perspective on the present. Wechsler’s “Freedom of Information” series comments on complications of remembering a radical individual. The series is inspired by censored Cold War-era FBI profiles of left-leaning artists like Alice Neel, Diego Rivera, and William Gropper. The works are impressionistic representations of the files released by the Freedom of Information Act, each with a colorful background marred by stamps, type-written text, black bars covering redacted information, and other hallmarks of government bureaucracy.

Wechsler’s series serves as a kind of dissenting voice to Cardenas’s bold, playful optimism. The wall of raw, splattered depictions of bureaucratic files stands directly opposite from a wall of bright, cartoonish depictions of familiar public figures. Cardenas’s caricatures let the viewer look back on history through the eyes of a participant, while Wechsler’s obscured FBI files comment on the suppression of speech and the alienated and estranged relationship between the artist, the historian, and the audience.

Cardenas’s caricatures, paintings, and political cartoons tell the intensely personal story of an outspoken artist in constant critique of his surroundings. “He was always drawing cartoons for the wrong side,” Franklin commented. While in school in Madrid, Cardenas worked for an anarchist union newspaper, drawing cartoons criticizing the totalitarian tendencies of Francisco Franco. When Franco came to power in 1939, Cardenas was imprisoned and sentenced to death for his political cartoons, only eventually released after the intervention of the Colombian Consul General.

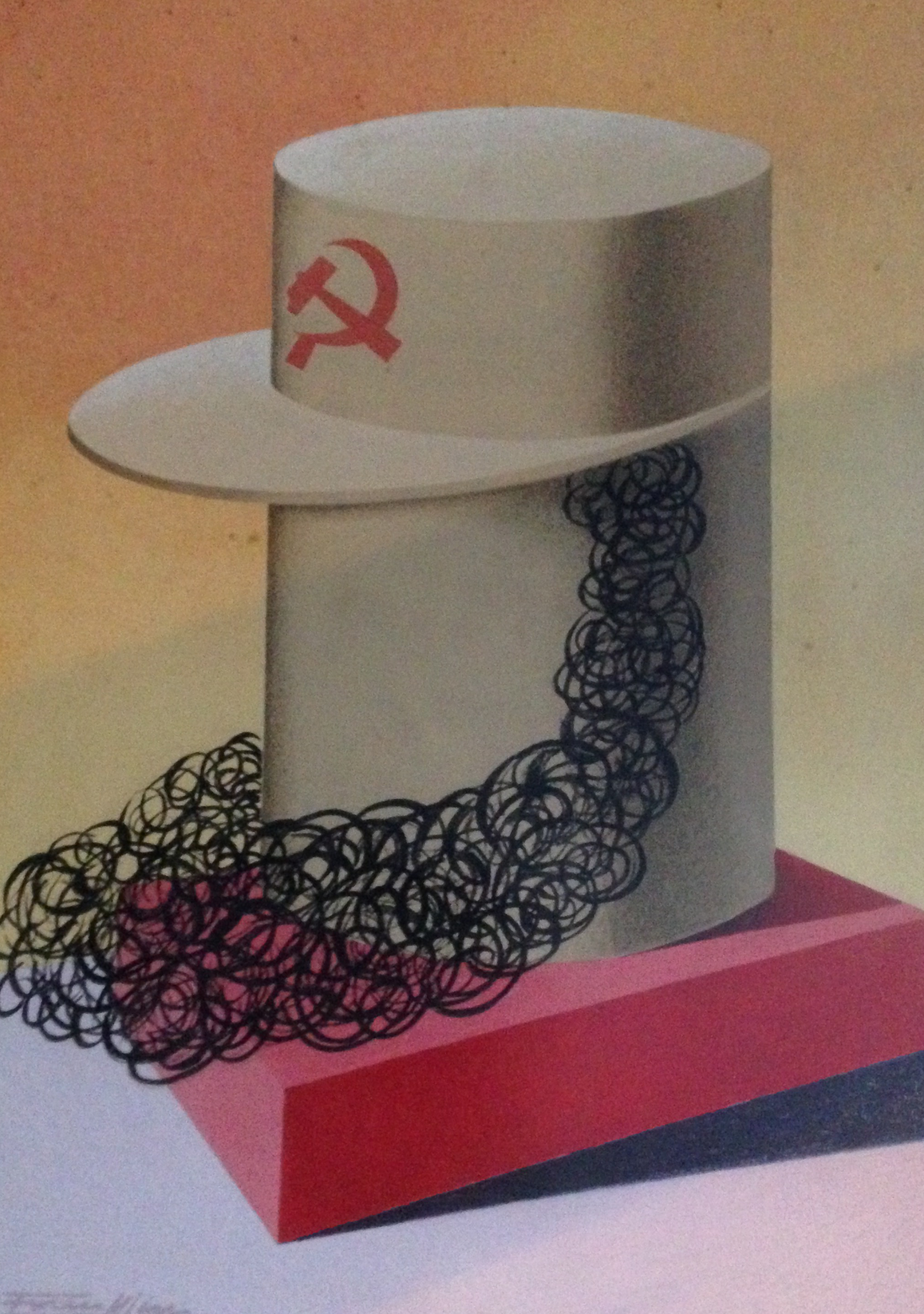

A collection of muted, monochromatic, paintings of Cardenas’s time as a prisoner prove to be the most emotionally striking part of show. The paintings of slumped, captive figures and corporal punishment show a personal experience of intense brutality and oppression. The most visually appealing and distinctive part of the collection is the wall of brilliantly colored, geometric, cartoonish caricatures of historical figures, ranging from union leader John C. Lewis to Che Guevara to Pablo Picasso, originally published as covers of the Colombian news magazine Semana.

Franklin framed the Cardenas collection as a lesson on the importance and contradiction of historical memory. “Living through history, you feel it—intensely, emotionally,” she said, referencing her own memory of the Kennedy assassination. At the same time, she emphasized the limiting scope of personal experience, and the perspective that history lends the individual. “History shapes the world we live in,” she said. “We don’t always think of it as history at the time, but ten or twenty years later we learn that it shapes everything.”

Rather than simplifying Joe Hill’s legacy or relying on the appealing visuals on display, “Joe Hill 100 Years Part 4” revels in the subtleties and contradictions of its subject material. At the opening of the show, Uri-Eichen hosted a panel to discuss the role and importance of the satirist in political expression. The panel emphasized the influence that a single dissenting voice could have on political discourse. In the words of panelist, historian, and journalist Rick Perlstein, “The court jester was the most powerful man in the kingdom because he could look the king in the eye and insult him.”

The legacy of Joe Hill and Jorge Cardenas, paired with the contemporary work of James Wechsler, furthers the discussion of the power of the radical artist. The art on display varies—colorful caricatures, paintings evoking government bureaucracy and censorship, pithy black and white political cartoons, political campaign posters, raw depictions of captivity—but it all conveys an immediacy and vibrancy crafted in opposition to oppression or injustice the artist found worthy of opposing.

Uri-Eichen Gallery, 2101 S. Halsted St. By appointment through May 1. Closing reception May 1, 6pm-9pm. Free. (312)852-7717. uri-eichen.com

Excellent article! It explains very well the relationship of the various artists, who are apart in time and mode of expression but relate in theme. And it zeroes in on the emotions engendered by the paintings.

Are you the same Shannon that was friends with my Parents Lou and Patricia Gothard when they were living on Dorchester in Hyde Park? My name is Jeffrey and my sis in Jennifer. We all live in southern CA now, but I’m here to set up my own son Noah Bear Gothard who starts at Loyola UC this fall.

Is that David’s wife? My old Chi friend Is Stephanie your sister? My son and his family are visiting Chicago right now I remember going to that park near your sister’s place on Kenwood on the /63 eclipse and the metal of the slide was cold Now at 57 Jeff has brought the family there as his son Noah is going to Loyola for college

I spelled my name incorrectly

Yea, Patricia, Jeffrey and Noah…it’s us! Since they don’t publish emails or phone numbers here, it’s hard for us to get in touch with you. But do call. We’ve had the same phone number and address in Evanston for the last 44 years. Love to you all.

Shannon and Dave