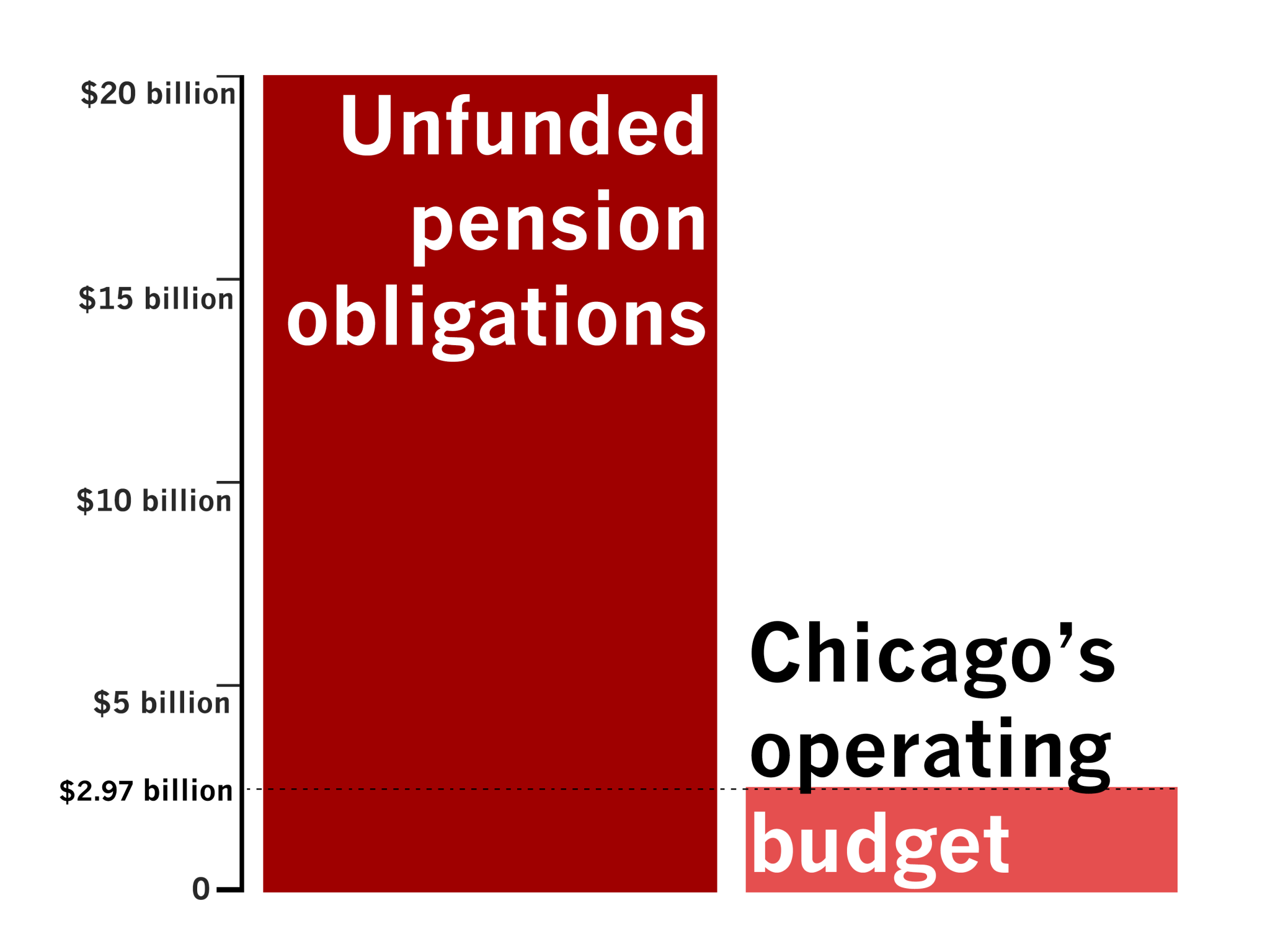

On October 28, the Chicago City Council approved a 65% property tax increase proposed by Mayor Rahm Emanuel to head off the city’s looming police and fire pension crisis. The hike is expected to bring the city $543 million for those funds by 2018, an amount that will put only a modest dent in the city’s $20 billion in unfunded pension obligations.

Who will the hike hit the hardest? As it stands, most South Side homeowners will be unaffected, while landlords and their tenants could feel more of a pinch. Emanuel’s proposal increases the “homestead” exemption offered to all homeowners from $7,000 to $14,000, making the tax more progressive than it currently is—for those with property worth much more than $250,000, the increased tax rates will outweigh the increase in exemption. Because there are only a handful of South Side neighborhoods where most homeowners own properties worth that much—Hyde Park, Kenwood, Bronzeville, and most of Bridgeport—most South Side homeowners won’t be paying any more in property taxes.

But the “homestead” exemption doesn’t apply to business owners and landlords. As a result, those two groups will actually pay a bit more in taxes next year given increased tax rates elsewhere in the budget.

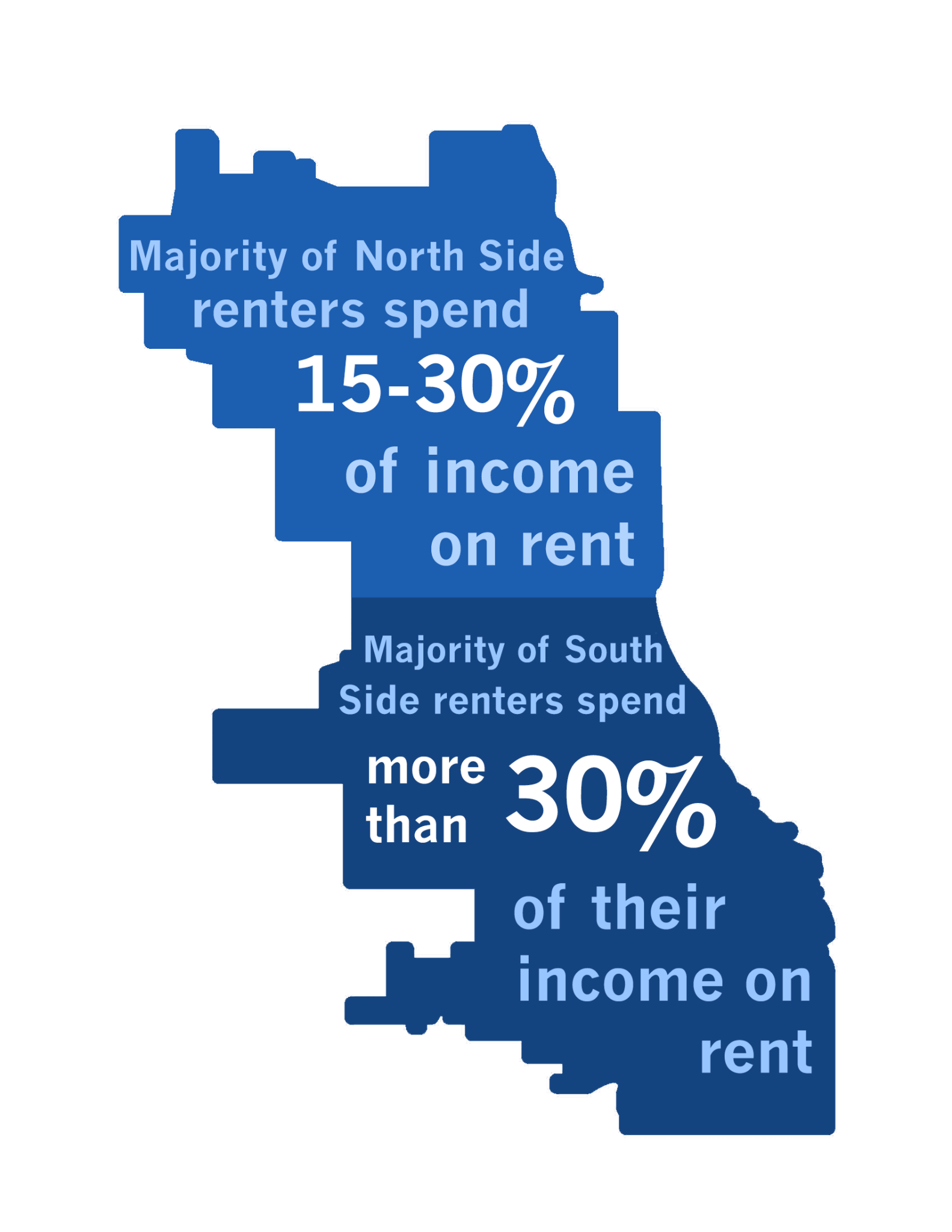

One big worry for South Siders is that landlords will pass these higher tax rates on to their tenants. Most South Siders are renters; over two-thirds of the South Side’s community areas have populations in which a majority of households rent. And most of these neighborhoods have an affordability crisis: the overwhelming majority of South Side census tracts see renters spending more than a third of their income on rent. This isn’t the case on the North Side or in the more affluent areas of the West Side. If property taxes cause rents to rise across the city, renters in Washington Park and Englewood will find it harder to pay their bills than renters almost anywhere else in the city, and the South Side as a whole will be disproportionately impacted.

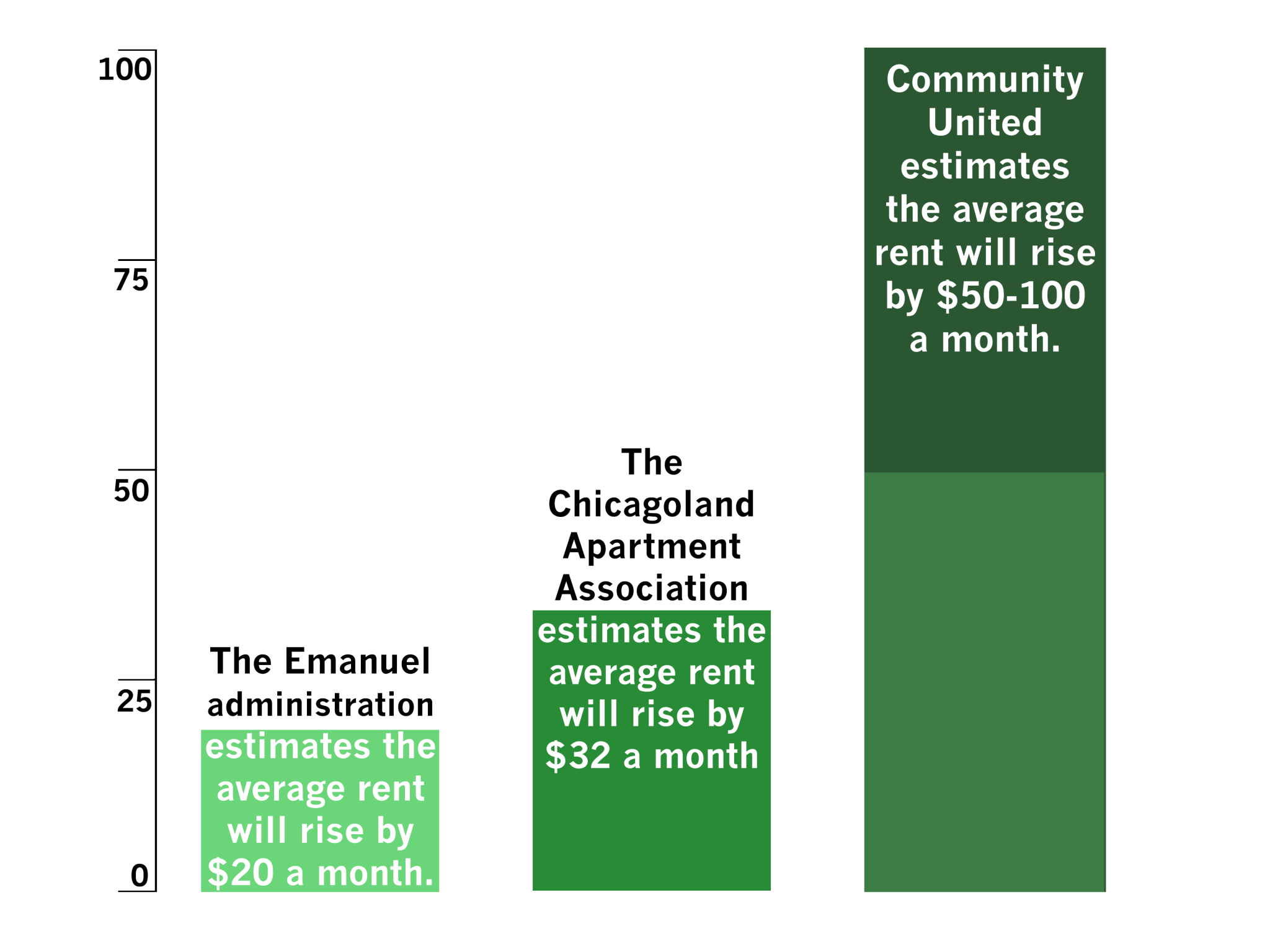

Estimates differ on how much the tax hike will produce higher rents. The Emanuel administration estimates that an average apartment unit will see an increase in rent of about twenty dollars a month, or $240 a year. The Chicagoland Apartment Association contested these figures, predicting the cost would be closer to thirty-two dollars more per month.

It is also not clear how applicable these estimates are to the South Side. Unlike the North Side, South Side neighborhoods tend to have vacancy rates much higher than the city average, and the Emanuel administration has claimed that high rates of vacancies will make it hard for landlords to pass the cost of the tax hike on to their tenants. But Christopher Berry, a professor of public policy at the University of Chicago, is doubtful. “It would be very surprising if the renter paid nothing,” he says. “As for the exact fraction the renter pays and the landlord pays—there are papers at both extremes. You can pick whatever result you want out of the literature. The city is right to emphasize the fact that there seems to be a lot of excess supply.”

“The more of the tax that is borne by the landlords, the more we expect landlords to adjust in the long term,” he continues. “The city may say that’s not such a problem because we have an excess of supply. But it seems hard to reconcile an affordable housing shortage with excess supply.” Additionally, the fact that low-income renters may find it harder to switch to a new apartment than higher-income renters—especially given that some at the bottom of the market might not be able to find apartments that are cheaper than the ones they already live in—might give landlords more leeway to increase rents.

The concern that landlords and their tenants would bear the costs of the exemptions provided to other homeowners was among the reasons behind the critique of the exemption advanced by the nonpartisan think tank the Civic Federation, which endorsed the tax plan overall. “[Homestead exemptions] should be limited and targeted to the lowest income homeowners and renters,” the Federation wrote in a report on a proposed budget last month, “because property taxes in Cook County are a zero-sum game, meaning that tax relief provided to one property owner must be paid for by all other owners.”

The Federation recommended an income-based “circuit-breaker” solution: a tax relief program run by the state through the state income tax “designed to provide relief when a person’s property tax liability exceeds a certain percentage of their annual income.” This would target relief specifically at low-income homeowners on the South Side and across the city and potentially reduce the burden on landlords and renters by preserving revenue from the tax hike. The Chicago City Council’s Progressive Caucus, which includes seven South Side aldermen, also advanced an alternative: a program that would, like the Federation’s “circuit-breaker”, target relief at low-income homeowners by giving a tax rebate to households earning an income under four times the federal poverty line.

Even though the budget has passed City Council, the city may have to look to these and other alternatives to increase the homestead exemption, given that the measure is unlikely to pass in Springfield, where it requires both a vote in the legislature and Governor Bruce Rauner’s signature. Rauner, who strongly opposes a property tax hike in Chicago, has already suggested he will veto any component of Emanuel’s plan that requires state approval.

The city is also awaiting the passage of another piece of crucial fiscal legislation in Springfield. Current city projections assume that state government will approve Senate Bill 777, which extends the timeframe of the city’s requirement to adequately fund pensions by fifteen years. If the bill isn’t passed, the city will owe $843 million more over the next five years than it has currently budgeted. Governor Rauner opposes that bill as well. Additionally, the Illinois Supreme Court could overturn recent reforms to municipal worker and laborer funds. Both that and the failure of Senate Bill 777 would mean that the city’s pension funds would face solvency issues even with the property tax increase.

Between the dim prospects of the homesteader’s exemption and Senate Bill 777 in Springfield, the city’s finances are murky. The same can be said of the finances of the South Side’s renters, who may or may not face rent increases as a result of the tax hike. Amid the chaos, one thing is clear: the burden of the hike will not be felt equally across neighborhoods.

Simply, cool!