One wouldn’t have needed to be in Wrigleyville on the early morning of November 3, 2016—when the Chicago Cubs won the World Series, igniting a citywide celebration more than a century in the making—to know that Chicago loves baseball. That championship team was notable not only for its Series victory but also for the four African-American players who played major roles throughout the 2016 regular season and playoff run. In an era of a well-documented dearth of Black players in Major League Baseball (MLB) compared to previous decades, center fielder and leadoff hitter Dexter Fowler (now with the rival St. Louis Cardinals), right fielder Jason Heyward, shortstop Addison Russell, and relief pitcher Carl Edwards Jr. represented a noteworthy exception to a sport-wide trend. In many ways, it’s fitting that a roster with four Black players—tied with the Boston Red Sox for the most in the MLB—took part in bringing a championship back to Chicago, a city that has played such a major role in the history of baseball in the African-American community, and that is spearheading the MLB’s efforts to revive baseball participation in inner cities nationwide.

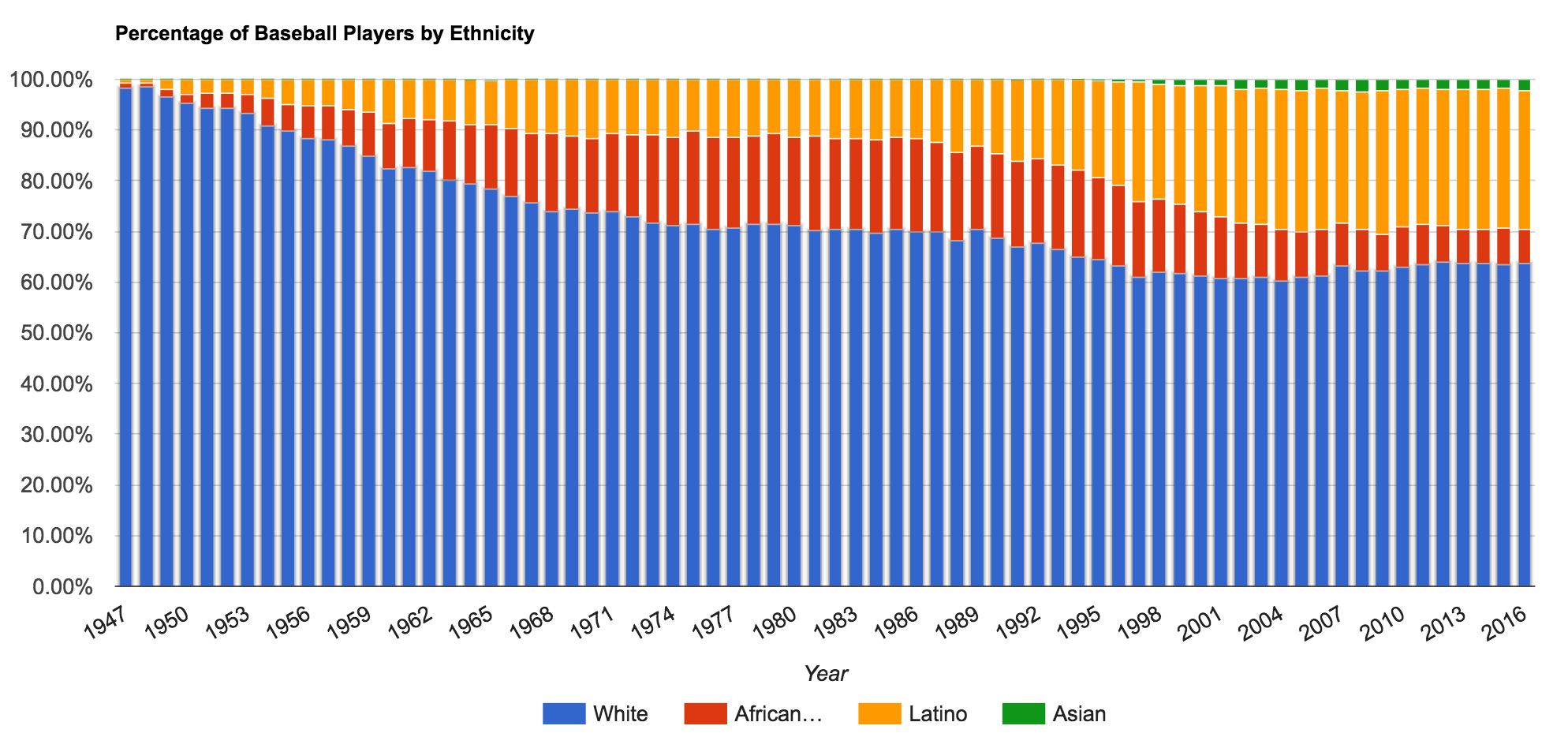

April 15 marked seventy years since Jackie Robinson started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Although it would take until 1959 for every MLB club to integrate, the following decades would see many Black players ascend to superstardom. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, African-American players consistently made up at least seventeen percent of all players in MLB, and players such as Darryl Strawberry, Willie Stargell, George Foster, and Joe Morgan were among the most-feared hitters of their eras. Even through the 1990s, a steady stream of African-American stars—like Barry Bonds, Ken Griffey Jr., and former White Sox first baseman Frank Thomas—anchored strong Black participation in baseball from the majors to Little League.

But by the turn of the century, it was clear that something had changed. The percentage of African-American players in MLB was down to twelve percent by 2001 and falling fast; according to the Society for American Baseball Research, only 6.7 percent of MLB players were African-American during the 2016 season. Some of that decline can be explained purely through numbers: as the percentage of African-American players was halved, the percentage of Latino players was doubled. In 1989, thirteen percent of MLB players self-identified as Latino; that proportion was over twenty-seven percent in 2016. As MLB expanded their talent searches southward to the nations of Cuba, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic, scouts were able to find thousands of players, many as young as sixteen, who could be signed cheaply under league rules as international free agents. Statistics at least somewhat illustrate that MLB and other baseball officials have shifted their recruiting efforts away from African-American communities.

To David James, however, those numbers don’t tell the whole story. As Vice President of Youth Programs for MLB, James oversees the league-administered Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) initiative. Founded in 1989, RBI now sponsors programs in some 200 cities across the United States through partnerships with all thirty MLB teams, serving 200,000 children annually. According to James, the cost of playing baseball—especially when compared to basketball—“is the number one issue” that hinders kids in underserved communities. “The game has not become too expensive; it’s the whole travel ball, pay-for-play that has,” James said, explaining how the rise of the travel baseball industry impacted overall youth access and participation. “Grassroots, local league play got hit hard by the better kids who felt that the competition wasn’t where it should be, so if they had the means, they went and played for another program, and ultimately the grassroots community-based local leagues started to diminish.” Also citing shrinking parks and recreation department budgets as a barrier to access, James notes how RBI prioritizes providing affordable opportunities to play baseball to what he calls “underserved kids, underserved communities” across America.

James is aware of the uphill battle faced by MLB and other proponents of youth baseball. As he said with regard to the decline in the percentage of African-American players in MLB, “It took a long period of time for the number to drop, we’re not going to be able to turn it around overnight.” But pointing to recent successes of the RBI initiative—ninety RBI alumni have been drafted in the MLB first-year player draft over the past nine years, and established players CC Sabathia, Yovani Gallardo, and Justin Upton all count themselves as RBI grads—James said, “I’m confident that there is an upswing in participation of African-American youth in locations across the country.”

Chicago, in particular, “is one of the best-kept secrets in the country with regard to African-American kids playing,” said James. Lauding the White Sox and the Cubs for their model efforts in promoting youth participation through league-sponsored programs, James said that opportunities provided to Chicago youth over the past decade are beginning to show dividends. Referencing South Sider Corey Ray, who played for the White Sox Amateur City Elite (ACE) team as a teenager and collegiately at the University of Louisville before being selected fifth overall by the Milwaukee Brewers in the 2016 MLB draft, James said that “over the next four, five, six years, you’re going to see a lot of kids that potentially are Major League-caliber players that are going to come out of the city of Chicago.” Still, James maintains that the primary intention of RBI and other league efforts is to instill positive values and teach life skills through baseball. “Our first responsibility is to create major league citizens. If we get Major League players out of it, that’s a bonus.”

To Coach Kenny Fullman, his job is “to try and get more inner city and African-American players from the city of Chicago playing baseball at a high level.” Fullman says he began his career in youth baseball at the age of fourteen, when he started coaching his younger brother’s peewee league team at the request of the president of the Washington Heights-based Jackie Robinson West Little League. In the years since, Fullman, who played baseball at Mendel Catholic High School in Roseland and at Kentucky State University, has become a leading figure in the revitalization efforts of youth baseball in underserved parts of Chicago. In his twenty-five years of coaching at Harlan Community Academy High School in Chatham, thirteen of his players have been selected in the MLB draft. In addition to working as a scout for the White Sox since 2003, he also recently became the second Black person to be inducted into the Illinois High School Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame.

However, it is arguably Fullman’s work with the White Sox’s ACE program—the crown jewel of Chicago’s youth baseball revival—that will prove most influential to the resurgence of youth baseball in Chicago. Alongside Nathan Durst, Fullman founded the ACE program ten years ago in response to what they saw as a troubling lack of access and exposure to college and pro scouts for Black players from underserved neighborhoods. With the blessing and support of the White Sox, the ACE program has offered an opportunity for hundreds of kids—at least seventy percent of whom live in low-income areas—to play elite, travel baseball year-round, with professional-caliber facilities and instruction. To Fullman, who serves as director, the ACE program has a simple objective: “We’re leveling the playing field.” Fullman mentioned many of the same hurdles to participation as James, cost being chief among them. “Money is a big thing about baseball now. The grassroots programs are getting watered down and travel baseball has become big. A lot of times, our kids didn’t have accessibility to the tournaments, or the equipment, or the uniforms that a lot of the affluent kids did. Baseball is becoming an affluent kid’s sport.”

Since the program began in 2007, over 130 ACE alumni have received college scholarships to play baseball, said Kevin Coe, Director of Youth Baseball Initiatives for the White Sox. Fullman notes with pride how many of his ACE players have gone on to “schools we would never have imagined them going to…in the SEC, the ACC, the Big Ten…all across the country, we’ve got kids playing baseball from the inner city of Chicago.” This is no small feat, considering that the declining numbers of African-American players in the major leagues have extended to the college ranks as well; in 2015-2016, only 3.3 percent of Division I baseball players were African-American. One ACE alumnus, Corey Ray, already has a clear path to the majors, and according to Coe, others shouldn’t be far behind. “We have several young men that are playing in our program right now that…have the potential to play some high level baseball. We have several [players] who are playing in college right now that might have the opportunity to play professional baseball.”

The current renaissance of baseball programs in African-American communities in Chicago has deep historical roots. In the decades before the integration of the major leagues, Chicago was a hub for Black baseball in America. African-Americans on the South Side played on “industrial league” teams operated by Black-owned businesses throughout the 1910s and 1920s, and some of the first attempts at establishing a formal Negro League came out of Chicago, according to Dr. Leslie Heaphy, history professor at Kent State University at Stark. When the Negro National League was founded in 1920, it was due to the efforts of Rube Foster, a longtime Chicago resident and “the father of Negro League baseball.” Foster’s newfound league would include two Chicago-based teams, the Chicago Giants and the Chicago American Giants, both of which played on the South Side. Further demonstrating this connection, Schorling’s Park—now the site of Wentworth Gardens in Bronzeville—hosted the 1924, 1926, and 1927 editions of the Colored World Series, while throughout the 1940s, Comiskey Park hosted the East-West Negro League All-Star Games, which regularly drew upwards of 45,000 spectators.

Certainly, Chicago’s relationship with Black baseball has at times been fraught. The White Sox wouldn’t debut an African-American player until 1951, four years after Robinson’s first appearance with the Dodgers; the Cubs would even more stubbornly resist integration, as an African-American player would not wear a Cubs uniform until shortstop Ernie Banks made his debut in 1953. (Banks, “Mr. Cub,” would have an illustrious career and is now regarded as perhaps the greatest Cub of all time.)

Even after Banks had established himself as a franchise player, both internal and external barriers to further racial integration persisted. Buck O’Neil, himself the Cubs’ first African-American scout, was responsible for the signings of many black players throughout the 1960s, including promising outfielder Lou Brock. Reflecting on the difficulties still faced by African Americans in baseball nearly two decades after Robinson broke the color barrier, O’Neil wrote in a 2002 essay, “There was an unwritten quota system… They didn’t want but so many black kids on a major league ballclub.” One only needs to look to Brock to see evidence for O’Neil’s claim. Brock was traded to the Cardinals in 1964 amid rumors of racial discontentment among the Cubs’ largely white fanbase, as part of a package that netted the Cubs pitcher Ernie Broglio. Brock and the Cardinals would go on to win the World Series that year, and over the next fifteen seasons, he would play his way into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, while Broglio would be out of the league by 1966.

The recent accomplishments of the White Sox ACE program, the MLB-sponsored RBI initiative, and young players like Corey Ray all represent a citywide renewal and rejuvenation of baseball. And there are signs of progress on a wider scale, as well: over twenty percent of first round draft picks over the past five years have been African-American players, and three African-American players—Hunter Greene, a high school shortstop and pitcher from California; Kentucky high school outfielder Jordon Adell; and Jeren Kendall, a Vanderbilt University outfielder—are among the top prospects for the 2017 MLB draft. Through it all—through the decades of outright segregation, the long and difficult path toward integration, and, now, the declining numbers of African-American players at all levels of the game—baseball has survived in the underserved and African-American neighborhoods of Chicago.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.