Leer en español. This story was produced by City Bureau.

On a Sunday afternoon this April, Elaine Olszewski, a lifelong parishioner of St. Adalbert Church in Pilsen, walked down the church stairs to the rectory basement. As president of the Mothers Club, she was ready to decorate the tables with matching paper cutlery and placemats for the club’s weekly meeting. Instead, she was shocked to find the usually tidy room in disarray.

Strewn about the room were dirty mattresses, empty beer bottles, pizza boxes and small bags of marijuana. The walls were covered in graffiti and the windows had been taped over with brown paper bags.

“Nobody knew anything about it,” says Olszewski. “At least the priest could have called and let us know that the meeting was canceled.”

Another parishioner eventually informed her and others that the basement had been rented out as a set for an upcoming television show. The small bags of marijuana and graffiti were fake. This was news to the small group of eighty-year-old women who were forced to reschedule their Mothers Club meeting.

When the Archdiocese announced in February 2016 that it would be consolidating Pilsen’s six churches into three, parishioners at St. Adalbert could not have imagined how messy that would look. Canceled classes and events meetings became more and more common. There was a failed real estate deal, several preservation societies and a legal challenge that went all the way to the Vatican. Through it all, St. Adalbert’s most dedicated worshippers say they’ve been let down and left out by the institution in which they placed so much trust. Those who are still fighting are running out of options.

They’re not alone. In September 2015, the Archdiocese of Chicago announced the Renew My Church initiative, which purported to strengthen the existing church community while encouraging the faithful to bring others into the fold. But the most visible and controversial part of the plan is the “parish grouping” process, which organized Chicago’s nearly 400 parishes into ninety-seven groups. Each group shares a priest, a budget, a finance council and a parish council.

In the process, the Archdiocese has moved to close ten churches—including St. Adalbert’s. This year alone, it announced eighteen new parish mergers, which entailed eight church closings. Recently, another Renew My Church merger in Chicago has drawn ire in Bridgeport, Canaryville, and Chinatown.

Some Chicagoans, like St. Adalbert parishioner Anina Jakubowski, refer to the program as “Ruin My Church.” She says, “There’s nothing positive about it. It’s very much decimating any church that has any bit of congregation there.”

By many measures, the Catholic Church is in crisis. Mass attendance has dropped thirty-five percent since 1990, according to its own numbers. The number of priests has also declined, and too few are being newly ordained each year. With fewer parishioners comes fewer donations—and the Church has also spent millions settling lawsuits in the priest sex abuse scandals that have swept the globe.

For an organization facing less demand with fewer financial resources, consolidation can make a lot of sense. But as the parishioners at St. Adalbert have seen, and as the Archdiocese of Chicago is finding out, closing a church can be just as difficult as keeping one open.

Founded in 1874, St. Adalbert is located in the heart of Pilsen on 17th Street between Paulina Street and Ashland Avenue. Its towers, built brick-by-brick by Polish immigrants, are visible no matter where you are in the neighborhood. Inside, the marble columns, 100-year old Kimball organ and stained glass windows are modeled after the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome.

The church, once worship site for a largely Polish base of parishioners, now serves a diverse community of Mexican and Polish worshippers as well as new residents of Pilsen.

When Mexican immigrants began to settle in Pilsen throughout the 1960s, the churches were some of the first organizations to welcome them to the neighborhood. St. Adalbert’s, for example, added Spanish-language Mass to its rotation in the mid-1970s.

It took nearly 150 years to build St. Adalbert into the community it is today, and about ten months to decide to close it.

In April 2015, priests, representatives from the Dominican and Jesuit religious orders and archdiocesan officials met to begin the planning process to consolidate or close Pilsen parishes. These meetings continued through the summer and in September, a brief presentation about the process was given at a prayer service at St. Adalbert, open to the entire community. The Archdiocese says non-leadership parishioners from each church joined a “newly developed steering committee” which met regularly in the fall, before the final recommendation was made.

family has been a part of the St. Adalbert community for two generations. (Max Herman / City Bureau)

The Archdiocese solicited feedback through “multiple meetings that parishioners could attend at their individual parish” and a survey distributed at Mass, according to Anne Masselli, director of communications.

“I don’t think they involved the community. From what I understand, the ones in charge of the church were the ones more involved in the process but I don’t think, I’m not sure, but I don’t think they ever asked us if we wanted [our church closed] or not,” says Ofelia Andrade, a parishioner for fifteen years.

Father Michael Enright, priest of St. Adalbert’s, declined to comment on this article. But some parishioners feel that their parish was not adequately represented in these planning meetings. At the time, St. Adalbert did not have its own dedicated priest to advocate on its behalf, as Father Enright was in charge of both St. Paul and St. Adalbert, and only a select group of individuals were allowed to attend the meetings.

“We’re not sure why certain parishioners feel they were not aware of the decision-making process, as it lasted nearly a year and was designed to include input from all of the affected parishes,” Masselli wrote in an email.

When asked if the Church had changed its approach to church closings after hearing from parishioners upset about the St. Adalbert process, Maselli wrote, “As for lessons learned, we now have a formalized process and we have additional, experienced resources to accompany the parishes through the decision-making process and to provide guidance and to help implement the new operating plan post-consolidation, when necessary.”

Once the decision has been made to close a church, the Archdiocese begins a process not unlike selling any other large building. It hires brokers, who assess the value of the property and put it on the market.

Eric Wollan, director of capital assets at the Archdiocese of Chicago, describes the decision to sell a church as a matter of maximizing its value to the parish it serves. When church attendance is low, he says, “ultimately we recognize that we have facilities that aren’t central, aren’t critical to the church’s mission or the parish’s mission going forward.”

If the St. Adalbert property is sold, the proceeds will follow its parishioners to St. Paul, Wollan says.

But selling a church has its own unique challenges. Unlike other properties, a former church needs to be deconsecrated, or stripped of its spiritual designation, before it can be repurposed. The process involves an official decree from the church, in this case from Archbishop Blase Cupich of Chicago, saying the property is no longer a house of worship but still cannot be used for “profane” purposes.

Other church stipulations can be enforced in perpetuity through deed restrictions, explains Angelo Labriola, vice president at SVN Chicago Commercial and one of the lead brokers for St. Ann and St. Adalbert. The St. Adalbert deed includes a long list of restrictions, including prohibition of human cloning, contraception, Satanism, palm-reading, porn, auto body shops and anything that “portrays unlawful activity or lifestyles in a favorable light.”

The Archdiocese entertains a range of suitors, but most commonly deals with residential developers and educational institutions, according to Wollan. A few high-profile church conversions in Chicago have included luxury condominiums, event spaces and even a school for circus performers.

Labriola estimates that a property like St. Adalbert’s—with its 100,000 square feet across four buildings, on top of a 2.14-acre lot—could sell for a range between forty-five to seventy-five dollars per square foot. The buyer also needs to consider the rehabilitation costs, the construction costs to transform the building and the time it takes to secure a zoning change if needed. Depending on the buyer, the property may not retain its tax-exempt status, so property taxes are also a factor.

SVN has had St. Adalbert on the market since September 2018. In that time, Labriola estimates twenty to thirty groups have reached out to tour the property.

Potential buyers have come forward with plans that involved demolishing all the buildings on the lot, says SVN vice president Paul Cawthon, who is the other lead broker working with Labriola on the sale. But the church will not accept those bids, he says, even though those developers could likely offer a higher price than someone looking to preserve the buildings.

“St. Adalbert’s first and foremost is a stunning church, so the intent is always to save the church [building],” says Labriola. “[The buyer] needs to be able to come up with a viable plan, for the future of the church and for the property.”

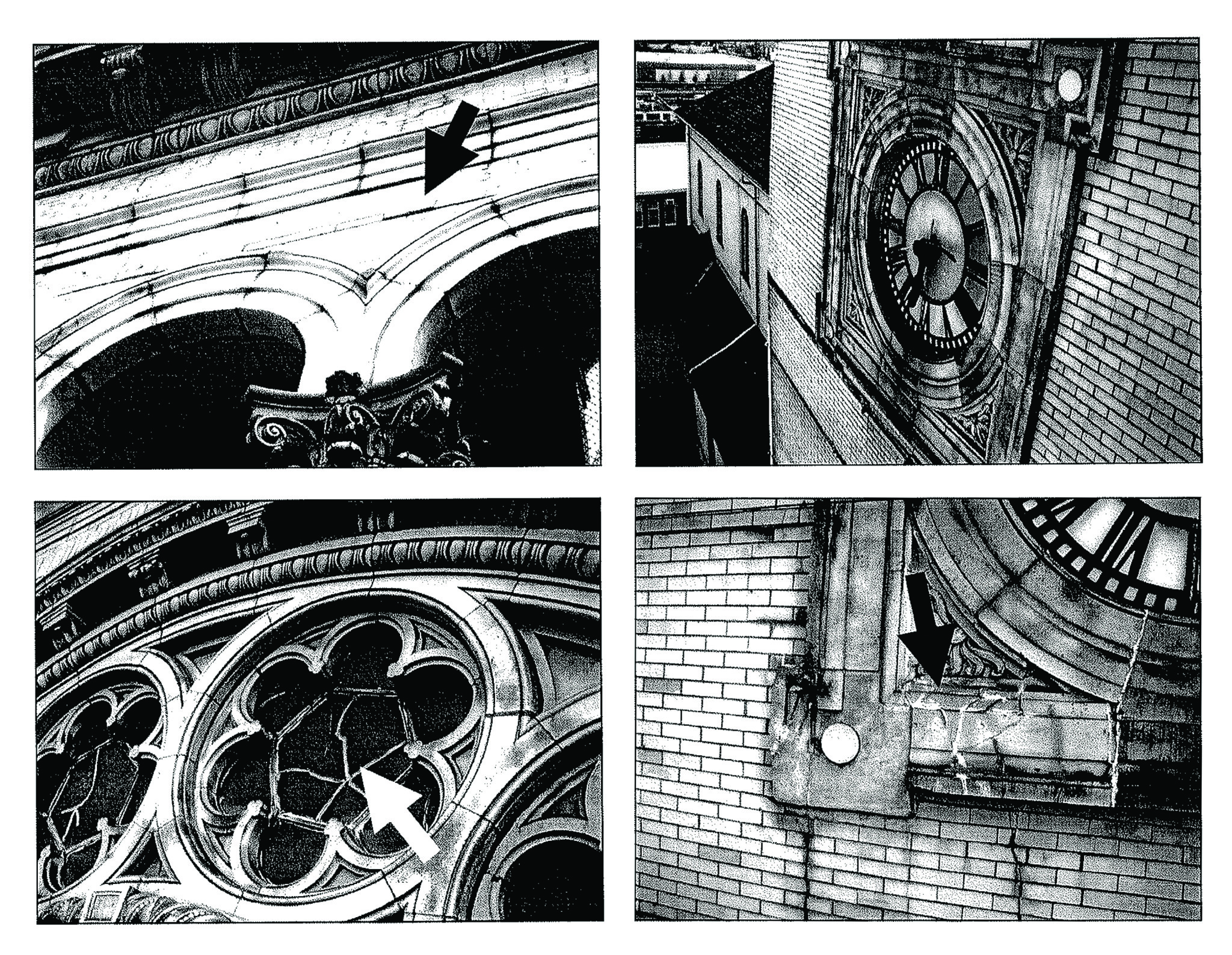

Cawthon and Labriola estimate that repairs to make the convent safe for use would be between two to three million dollars. As for the actual church structure, Cawthon estimated repairs to the towers would cost another two to five million.

And those millions of dollars in repairs are before a developer can turn the building into anything else. That’s all to say, anyone ready to buy St. Adalbert needs to have at least a few million handy. And both brokers made clear that there are developers who have that kind of money and could take on a project like St. Adalbert’s—it all just depends on the plan.

“You can’t repurpose a church—it’s hard,” Cawthon explains. “What do you do with a church with 70-foot ceilings and one bathroom and, you know, needs millions of dollars in repairs?”

Blanca Torres was with her fellow St. Adalbert parishioners at the Valentine’s Day dance when she heard her church was closing.

Torres grew up across the street from St. Adalbert’s. She went to grade school there, and her parents were some of the people who first petitioned for a Spanish-language Mass in the early seventies. Her dad was as an altar server and her mom taught catechism classes on the weekend. When they grew older, her sister was married and even baptized her kids there.

“I was crying and stuff, and my mom was, too,” Torres says of the moment they found out St. Adalbert would shutter its doors. “I said, well, OK, get that out of your system—cry, whatever—but then we need to formulate something that we need to start doing.”

Soon after the announcement, Torres and eight other parishioners created the St. Adalbert Preservation Society (SAPS), which incorporated two months later as a nonprofit and started fundraising. Guided by Brody Hale, a lawyer from Massachusetts who started the Catholic Church Preservation Society, SAPS was able to navigate the process of becoming a non-profit. Blanca says Hale was able to teach parishioners how to slow the process of closing their churches and how to preserve their churches.

SAPS held street fairs and collected money to repair the towers. They even received a one million dollar donation from an anonymous former parishioner.

The group also embarked on the years-long appeal process within the Catholic Church, challenging Archbishop Cupich’s decision to close St. Adalbert and bringing the case all the way to the Vatican—though that effort didn’t halt the sale of the church.

In the meantime, SAPS backed a November 2016 proposal by The Resurrection Project, a Pilsen-based nonprofit that works on community development and affordable housing, which would convert the complex into a mixed-use project including a worship space, theater and administrative offices.

The fight to save the church drew the attention of Julie Sawicki. Growing up, she remembers that when someone in the Polish community hosted a wedding, communion or baptism at St. Adalbert’s, that was something special.

“St. Adalbert’s was… the first Polish church to be built on the South and Southwest Sides of Chicago,” she says, noting the importance of the grand cathedral style. “The fact that our ancestors were able to achieve this feat in a foreign country was something very special for us.”

Sawicki joined the St. Adalbert Preservation Society in January 2017, but after several months, decided to create a splinter group when she and several other members from the Polish community had a different vision for the church—they wanted the majority of the property to remain a religious complex.

“That’s what our ancestors sacrificed for,” she says. “They didn’t come to this country to make a better life for themselves and their families and then sacrifice and work for free and raise money for, years later, for this to be sold to a developer to make money.”

So Sawicki created the Society of St. Adalbert’s, and the group created a plan to convert the convent behind the church into a forty-room bed and breakfast. The B&B income could help pay for long-term upkeep of the church, Sawicki says, as well as help pay off the loans needed to repair the church.

Eventually, the plan backed by SAPS was rejected by the Archdiocese. Now, Torres and her group are preparing their own plan, which resembles Sawicki’s but is open to using more of the property to generate revenue. The group is considering leasing out the convent and the rectory to house office space for nonprofits, pop-up shops and local startups, she says.

A third route is being proposed by Ward Miller from Preservation Chicago, an organization that advocates for Chicago’s historic architecture and neighborhoods. “We should be looking at a Chicago landmark designation of the building, and using some of the city’s adopt a landmark funds to help preserve these buildings,” he says.

But, according to Masselli, “No viable plan has been presented to the Archdiocese during this period that would have provided for the preservation of the property and its continued operation, particularly considering the significant investment required to repair and stabilize the buildings.”

Though she did not comment on any particular proposal, she says, “The parish and the Archdiocese have been very open about the process and have spoken directly to many groups interested in the property. All potential proposals will be, and have been, considered.”

It’s been about three years since the consolidation of Pilsen churches was first announced, and St. Adalbert’s is still offering weekly Mass in English and Spanish, plus a mass in Polish on the first Sunday of every month.

There’s been a lot of uncertainty along the way. In fall 2016, the church was briefly under contract to be sold to the Chicago Academy of Music Conservatory, to become a concert hall and student housing. The deal abruptly fell through the following year. At the time, Masselli told South Side Weekly that though “there were many aspects of Chicago Academy of Music’s plan that were attractive, the plan proved ultimately not to be feasible.”

In late April 2019, word quickly spread that there was a new, serious buyer for the church. Father Enright told a few parishioners to start preparing for changes because by September 2019, after more than a century, the church might belong to someone else. Labriola and Cawthon, the brokers for the property, denied that any buyer was in place, and said that the church was still on the market.

Torres’ family has been at St. Adalbert’s for two generations, Jakubowski’s for three, and Olszewski’s for four. There are hundreds of people like them who, driven by their faith, have devoted their time and labor to make St. Adalbert’s what it is today.

“I don’t want to say that I’m not going to be a Catholic anymore…but at the same time the hierarchy is not making it easy for us to maintain our faith and I just think that’s a shame,” says Torres, reflecting on her experience fighting for her church.

Whether the building is open or not, parishioners say the church they remember has already closed. Weddings, quinceañeras, and other important events don’t take place at the church anymore. According to staff at St. Paul, they can’t plan events months in advance because they don’t know if the church will be sold by then. Occasionally, funerals still occur at St. Adalbert because they only require a few days to plan.

Maria Elida “Eli” Sanchez, started coming to St. Adalbert after another Pilsen church, St. Vitus, was closed in 1990. She remembers the day she was barred from celebrating el Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe, an important day of celebration for Mexican Catholics who honor the Virgin Mary.

“The saddest was on December 12 when they didn’t let us sing at 5 a.m. at the church,” says Sanchez. “We came to the nine rosaries and the day of the mañanitas they didn’t let us be in the church…It was Father Mike who didn’t let us. It was under his orders and if he says no, it’s no. If he says yes, then it’s a yes.”

When Jakubowski’s mother passed away she says she had to beg to have her funeral at St. Adalbert. Her mother was involved in helping to save the church from being closed in 1974, Jakubowski says, and up until her last moments, prayed for it to remain open.

Torres and other parishioners also describe being prohibited from making church repairs.

“They wanted to repair some issues in the rectory, and yes sometimes [Father Enright] allowed us to repair dire things, but hasn’t allowed us to make other repairs because it’s going to get sold,” Torres says.

Severing the ties people have to the church alienates them from their community, and without the community it becomes easier to justify the church’s closing, parishioners say.

“Cupich says these buildings can be done away with, that we need to concentrate on people,” says Torres. “I’m concentrating on keeping my community of faithful together as well, and if we could do it in our church it would be so awesome. When I see St. Adalbert, I see the beauty of the church but I see the beauty of my own community reflected back in there.”

For those who fear their own churches may be headed down the same road, Torres says, “We need to be working together to make certain that no harm comes to any individuals anymore, and that we work to make the parishioners—the community of faithful, the actual people—the most important part of the Catholic Church.”

Clemente Murillo has been a part of the St. Adalbert parishioner community since he was five. Now at twenty-seven, he volunteers every Sunday at the church selling candles, saint cards and prayer books in the lobby. He’s behind the counter during the 2019 Via Crucis, a massive performance and procession that takes place each Easter. (See photo essay.) He likes when Mass is full on days of celebration like this one, though he wishes he saw more of these faces every Sunday.

“But of course, with the whole talking of closing…I mean with anything, whether it’s a church or anything, [if] it’s closing, it doesn’t motivate you to come, because you’re thinking, ‘why am I going, there’s nothing that’s going to be gained from it,’” Murillo says.

The arguments about the financial hardships of keeping open Pilsen churches that have high-priced repair make sense to Murillo, but it can still be frustrating to hear talks of closing his childhood church.

“It’s a mix of emotions. You’re sad, angry, uncertain of course of everything else. But at the end you just come, you help because if it’s still open, you still need to come and help,” Murillo explains.

Murillo jokes that he is biased, and believes that of all the churches in Pilsen, St. Adalbert is the nicest one. More seriously, he notes that from most places in Pilsen, you can see the church’s iconic towers. He calls it a landmark.

When asked what he’ll do if the parish closes, he says he’ll probably just find another parish closer to where he lives in Little Village. But he understands why it would be the end of the road for some parishioners if St. Adalbert closes.

“It’s really like they’re closing your own home,” says Murillo. “Me personally, I know I could still go anywhere else, but this is what I know. I’ve gone to other parishes, they’re beautiful and everything, but it never feels like the one that you go to.”

This report was produced by City Bureau, a civic journalism lab based in Woodlawn. To learn more and get involved, go to citybureau.org.

To hear a radio version of parts of this reporting, visit southsideweekly.com/ssw-radio or subscribe to SSW Radio wherever you get your podcasts.

As President of the Society of St. Adalbert (SOSA), I would like to clarify that our plan is to maintain the religious character of the church and entire complex, as was intended by our immigrant ancestors who sacrificed to build St. Adalbert. In the perfect world, the Archdiocese of Chicago would keep this church open but since it has made the decision to close it, then our mission is to maintain it as close as possible to its intended purpose.

SOSA’s plan is a “shrine” plan and also relies on converting the convent into a retreat house (not just a B&B). Given St. Adalbert’s proximity to downtown Chicago and an L-stop nearby, we think it is an ideal location for a religious oasis in our urban environment. The retreat house would serve as our primary revenue generator to maintain the entire complex, instead of relying on donations from Holy mass as the Archdiocese currently does.

It is also important to note that the Pilsen community has resisted real estate development and newly-elected Alderman Byron Sigcho is also against real estate development at St. Adalbert’s. SOSA had the opportunity to meet with Alderman Sigcho several weeks ago. For these reasons, we are not sure why the Archdiocese would consider real estate development as the only solution for St. Adalbert’s. It is against the community’s wishes.

Most importantly, Pope Francis has stated that there is a “crisis of faith around the world”. We see that especially here in Chicago with our unprecedented violence, much of it perpetrated by our youth. St. Adalbert’s was once a vital part of the Pilsen community during its “golden age”. It seems to us that instead of shuttering our churches, we should be finding creative solutions to keep our church doors open and become relevant once again.

Baptized went to school at Saint Adalbert for 8 yesrs. Grandparents were active Parishioners almost from conception of the church. Priests were great people absolutely no kids were taken advantage of…Father Novak started a softball leauge we played other churches in the area. He paid for equipment and treated the players at Sam’s Malt Shop under the L on 18th Street next to Goldblatts Dept Store. Was a great neighborhood to grow up in . What happened ? Obvious isn’t it.