In late February, the National Public Housing Museum (NPHM) and Red Line Service, an organization that helps provide arts access to Chicagoans experiencing homelessness, hosted painter Nathaniel Mary Quinn to share his experiences growing up in the Chicago Housing Authority’s (CHA) Robert Taylor Homes. The artist talk and dinner was held at the NPHM’s temporary River North location as part of the opening of Quinn’s exhibit “Soil, Seed, and Rain,” which was on view at the Rhona Hoffman Gallery in West Town through March 28. The event was open to all, especially those who have or continue to experience homelessness, and was supported by a $40,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Quinn welcomed the attendees, who were crossing the room’s rows of chairs to get plates of warm food provided by the event. He began by providing a grounding of his artwork’s roots, which “harkens back to my upbringing in Chicago, growing up with Robert Taylor.… Residents living in that community were not seen—particularly as viable citizens of Chicago, as human beings.”

Quinn paused before adding, “But we were human beings. We had dreams. We had aspirations, there were things that we wanted to achieve. So, I was able to understand that. I feel very fortunate that, fast forward to today, that I’m in a position to make works of art that can highlight the underpinnings of one’s humanity.”

The Robert Taylor Homes was at one time the largest public housing project in the country, and was inadequately planned. Systemic inequities and disinvestment led to its infamous reputation of overcrowding and a lack of basic resources and safety. However, Quinn reminded the audience that these inequities cannot overshadow the individual and communal lives within these homes and their resilient connections.

Quinn described an early childhood memory about his brother Charles, with whom he no longer has any contact. “[Charles] says, ‘Nate, you know, mom used to whoop you all the time for drawing on the wall. One day, you made a drawing on the wall, and she’s going to spank you to teach you a lesson, right? And he stops her and says, ‘Wait, before you spank him, look at the drawing.’ And my mother and him looked at the drawing, and they both realized that there was some evidence of talent there. And ever since, my mom would let me draw on the walls of the apartment. The walls of the project apartment became my first drawing pad. And from that point on, I loved to draw.”

He continued, “My father would also sit with me at the table which at the time was like a piece of wood on top of milk crates. You know, this is real project living. This is the crème de la crème of the project living,” to which laughter burst into the room.

Quinn continued, “He would take the brown grocery bags from Super Jet. He ripped them in half and made them flat… and he ripped the erasers off my pencils. He would say, ‘Never erase a mark, for every mark that you make, you make for a reason. If you make a mistake, there are no mistakes. Find the way to use the mark.’ He also taught me how to draw from my shoulder. Most artists draw from the wrist, but my father said, ‘There’s no real mobility here. Use your entire arm as your tool.’ He was my first real teacher. And this is someone who could not read or write and had no formal education. I still use those tools to this day to make my work.”

Quinn lived with his mother, father, and brother until he accepted a merit scholarship to attend Culver Academies boarding high school in Indiana, about a two-hour drive away. Unfortunately, his mother unexpectedly died the month after he started classes, and his remaining family left their former home later that year.

To honor her, Quinn independently adopted his mother’s name into his before graduating high school. “My mother never had an education,” he said. “She never graduated from anybody’s school. And I thought if I use her name, like her first name as my middle name, they will have to print that on my high school diploma, and it will say Nathaniel Mary Quinn. So, I kept it up the rest of my life.”

Earlier in the talk, he discussed the history of education in his family and the importance of that diploma: “Having two parents who were illiterate, couldn’t read or write, and who had no formal education, I [went] to the local public school, which was a good school, but a school that in fact was absent of many other resources that more affluent communities enjoy.”

Quinn’s desire to honor his childhood continues to breathe its own life through his art. Each piece is deeply connected to people’s humanity. He grew up witnessing “addicts of all kinds, drug addicts, alcoholics, hustlers,” and his friends as “all gang members and drug dealers.” However, at a young age, he recognized that these circumstances and “things of that nature were also just a shadow of no form, no solidity, and no concreteness—that no one seemed to have cared about them over time” was the reality shaping their lives.

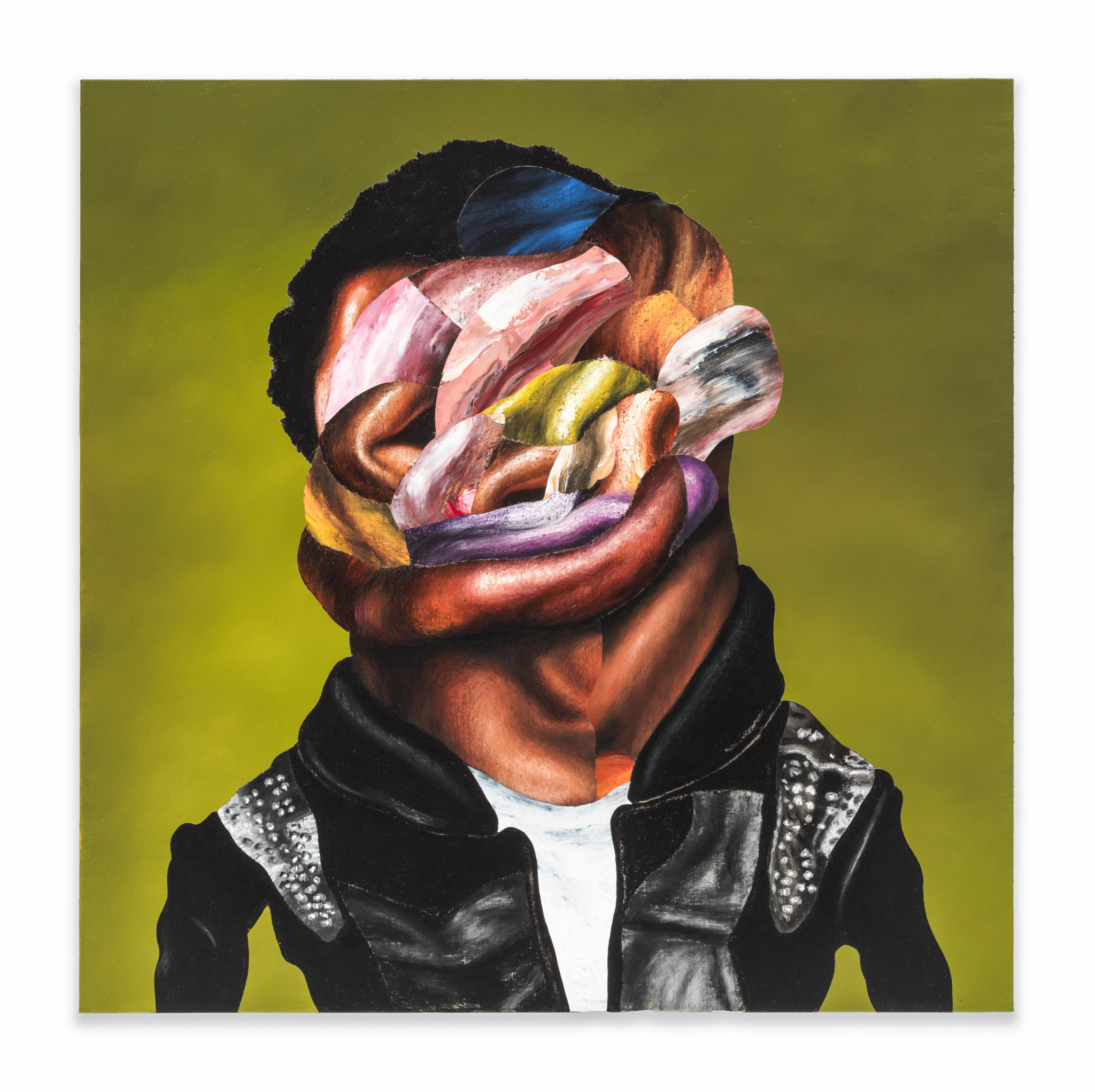

The final pieces presented that night represented his last living family member: his nephew, whom he is no longer in contact with. “Through [this painting], my nephew will live forever,” he said. The painting reflects his lost relationship to his unnamed nephew who broke his trust and lied. Quinn introduced him as “blood without commitment.” Then, Quinn turned to the audience and explained, “I imagined that…the pain of this betrayal is made permanent. So, this is really a true visual reflection of how I feel.” In describing his painting, Quinn speaks with humbled compassion about its subject.

Quinn’s work engages in realities without judgement, reflecting “another world that expresses real complexity and the rainbow light spectrum of humanity.”

He encouraged the room to accept that “when you look at this work, you’re not just looking at a reflection of this guy that none of you have ever met. You are, in fact, looking at a reflection of you. This is what you look like as well. Your identity is as complex and jarring and confusing and crude as this.” In sight, each portrait is a map from Quinn’s artistic and human dimensions.

Quinn emphasizes that complexity with his choice of materials. “I found these ways to combine these wet and dry materials together, which is not a particularly easy thing to do,” he said. It also allows him to connect to his childhood. “I love to draw. When you work with a paint stick, it’s a tool that you hold. There’s no brush, but it feels like drawing. That allows me to do the sort of things I’ve enjoyed doing ever since I was a child.”

Despite his paintings’ visual complexity, Quinn stressed they are not collages. He explained that this was how his childhood experiences and memories artistically present themselves, and encouraged the audience to carefully listen to each painting—his life experiences in that present moment.

Memories of growing up in the Robert Taylor Homes continue to influence Quinn’s artistic impulses. Quinn explained, “I just operate from the vision that is from my upbringing. Because growing up in the Robert Taylor Homes, you couldn’t really make plans every day because the violence was so high. So, the moment you stepped out your door, you had to be able to think fast on your feet. That is evident in my studio practice and it works for me.”

He went on, “and while that history is behind me, while it may seem that on some level that I am indeed disconnected from it, I am still at the same time very much connected to it.”

A final question perfectly ended the night. An audience member asked if he ever felt that he “needed to leave Chicago to find his voice, to find his [place],” leaving Quinn in deep reflection.

After pausing, Quinn concluded, “No, I did not feel that way. But when I left Chicago, that’s when I felt like I [was escaping] from poverty.”

“But you can’t run away from yourself.”

Images from Nathaniel Mary Quinn’s “Soil, Seed, and Rain” are available for view on the Rhona Hoffman Gallery’s website, rhoffmangallery.com

Jocelyn Vega is a contributing editor to the Weekly. She last wrote in March about census outreach efforts by the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights.

I lived in the Cabrini-Green Housing Project’s Myself, The Exhibition taught me how to Appreciate Life has You go through trails and tabulations, Nathaniel Mary Quinn’s Art taught me you can conquer anything in Life. And live your Dreams and make them come True.