Just north of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal is an ashen, defunct funeral parlor. At Oakley and 24th, the nineteenth-century, two-story building—still marked by a sign for “West Town Funeral Home”—is simple but striking, its stone exterior split by skinny lancet windows.

Inside are not crematoria and empty caskets, but a fully-working press. The building is now home to Hoofprint Workshop, a collaborative printmaking studio that can claim the title of southernmost printshop in Chicago.

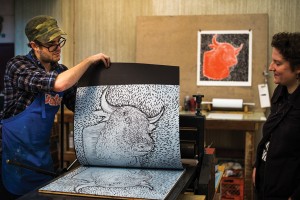

The two twentysomethings who recently founded Hoofprint, and also live in the building, are Liz Born and Gabe Hoare. Born specializes in relief and screen-printing techniques; Hoare focuses more on lithography and intaglio. Together, they’re combining their printmaking expertise to repurpose the old building into a studio, workshop, and teaching and collaborative space.

Inside is a spacious workroom, its walls hung with artwork that surround the room’s centerpiece, a Dickerson Combination Press that can be used for intaglio, relief, and lithography. In the unfurnished backroom is a large assortment of prints, woodcuts, lithographs, and raw materials; during a tour of the building in late October, there’s also a conspicuous, nearly-completed chupacabra piñata.

“We’ve had a number of piñatas at the shows that we’ve curated,” says Born, smiling. The papier-mâché veneer is yet to be applied to the figure, making it look like an avant-garde sculpture.

“This,” Born says, “is for our Halloween party tonight.”

The building wasn’t always this colorful.

“When we moved in,” Born wrote in a note, “the place was in full mourning-mode. Dim, rose-colored lamps illuminated a patchwork of shag carpeting, smelling of stale flowers and dust.”

As anachronistic as it might be, a sense of old-world glory is still preserved in the building. The notion that a one-time funeral parlor has been tactfully repurposed for the sake of printmaking—an art form that so readily lends itself to re-creation and preservation—seems fitting. “It’s such a specific place,” Born says about the building. “We can’t help but let it guide our direction.”

Hoofprint is, at its core, a collaborative space: the pair publishes prints in tandem with artists who may not necessarily share the same artistic backgrounds.

The workshop’s mid-October grand opening, a celebration entitled “Snap Roll,” featured a bluegrass trio and an exhibition of some of Hoofprint’s more recent collaborative work.

Some of those collaborative prints, including two recent works with artists Polly Yates and Sandra Perlow, still line the walls of the shop’s central room. “We like to work with artists whose backgrounds may not be in printmaking, because it lets them explore a completely different medium,” Born says.

“When we choose to work with an artist,” she continues, “it’s because we’ve crossed paths with them and we really respect what they’re doing. But we feel like we could help them branch out and expand their studio to the printmaking aspect.”

Typically, the artist covers the basic costs of supplies while Born and Hoare handle the actual printing process. In the end, the total number of prints produced is split between the artist and Hoofprint.

If publishing prints with outside artists is the duo’s primary goal, they also foresee other avenues of possibility—teaching private classes, working with youth arts programs, and expanding the space as a gallery. Currently, the press is open only by appointment, but beginning in December, Hoofprint will be open to the public on Fridays from noon to six.

The applicability of the printmaking technique means there’s always room to expand to mediums like comics and book arts. Born mentions Chicago’s lively underground comic scene as a way of potentially working with other media, and hopes that the Chicago Alternative Comics Expo, held every June, will allow them to collaborate with creators who are interested in the printmaking arts.

Born and Hoare emphasize that there is a fine distinction between a print and a copy—the former made by a series of complex processes, the latter merely a mechanical reproduction. “Even between prints [of the same image],” Born says, “there is some amount of variation.”

“Some people call them multiple originals.” The collection of these “multiple originals,” so to speak, is what forms the edition of a certain print.

Usually, once the pair have produced the desired amount of prints, they will mark or disfigure the original image. “It’s a way of protecting the artists’ interests if some of their prints or original artwork are ever exhibited,” Born explains. “It’s an issue of rarity.”

Nothing made at Hoofprint is a giclée, which Born explains is “a fancy word for an inkjet print.” The prints are handmade and therefore bound by the dimensions of the original image. There’s always an awkward exchange, she says, when a potential buyer points to a print and asks, “Can I get this in an eight-by-ten?”

“Images are so widely available—they’re everywhere and I think they begin to lose what makes them special…The Internet provides free content to our eyes.”

The old embalming room is located in the basement—what Born calls “The Lodge.” (“It’s like stepping into the basement of the fictional Great Northern Hotel from Twin Peaks.”) Though funeral services were held in the building as recently as last year, the embalming room hasn’t been in use for over fifteen years. Born and Hoare plan to retrofit the space, which by design is amenable to working with toxic fumes, as a kind of working space and storeroom for the acid-dipping process required for intaglio.

In this technique, the intended image is etched onto a copper plate that is treated with acid before being applied with ink.

“You put ink all over the plate and then you wipe it off, so ink stays only in the valleys. And then you apply it to the canvas,” Born says. The technique is the direct opposite of the relief process, where the actual incised image holds no ink, like a negative.

The Perlow pieces on display at Hoofprint—one called “Sitting Down,” another called “Strong Assumption”—are a good example of the physical dimensionality that mixed-medium prints can achieve. Whereas most painting is conceived in gradients of color and shading, printmaking is based in the study of contrasts. Think, for instance, of the negative image of a photograph. The same concept applies to printmaking.

Printmaking, Born and Hoare both concede, is an art form that naturally lends itself to collaboration, both in terms of the physical process and the necessity for space and equipment. Take the lithography technique, for instance, in which ink is applied to an aluminum plate. It’s a planographic process, meaning the surface remains flat throughout, unlike in other printmaking techniques. Instead, Born says, “It’s about hydrophobic and hydrophilic substances. The water is important to maintain the blank or non-printed parts of the plate.” So, often you need two people to print a lithograph: one person to apply the water with a sponge; the other to roll the paint on.

“It’s one thing to have your own press, but it’s another thing to share it,” Born says. “We’ll rent our press out to people who already know how to.” In the meantime, the duo will continue to grow the workshop into a space that involves classes and workshops.

“A lot of our mission is about educating people [about printmaking],” Born says.

An oft-impervious art form, printmaking is necessarily labor-intensive, requiring multiple processes that have to be repeated until the desired number of prints has been created. Similarly, many printmakers rely on communal or shared workspaces due to the expense and size of some of the equipment involved. The fact is that most artists and printmakers can’t afford to buy a press or have the space and the other materials required for their own workspaces.

David Jones is the head of Anchor Graphics, which he founded in 1990 in Wicker Park with his wife and partner, Marilyn Propp. The press moved to Columbia College Chicago in 2006 and is now a nonprofit—“We were just priced out,” Jones says—and still functions as a publishing press, but also as a teaching and collaborative space.

“When Marilyn and I started our printmaking workshop, there were only two other printmaking workshops that I knew of in the city,” Jones says. Landfall Press, founded in 1970, has since relocated to Santa Fe. Plucked Chicken Press was operated by its founder, Will Petersen, in Evanston until his death in 1994. But Jones insists that the community is a growing one.

In the nineteenth century, Chicago was something of a publishing giant—hence, historic districts like Printer’s Row, which was a fulcrum of the industry in its heyday. Even until the late 1970s, Dearborn Street was home to many printing shops, though most of the buildings along this area have now been converted into residential spaces.

Farther south was the Goes Lithographing Company, which for just over a century made its home in a 75,000-square-foot building at 61st and Perry. Goes left for Delavan, Wisconsin in 2010 due to issues with the building: the owners realized that the vibrations from passing trains would disturb new electronic printing presses. Norfolk Southern bought the building, which was demolished in February, and plans to build a truck depot on the site.

With the rise and fall of the printing establishment in Chicago, printmaking today has become something of a niche art. Hoare, for one, compares his art form to another, similarly archaic one: letter writing. “It’s like when you get a [hand-written] letter in the mail—you’re just like, ‘Holy shit. Someone actually took the time to write this by hand.’ ”

“It becomes a lot more meaningful,” Born echoes—whether it be a hand-written letter or a handmade lithograph. Printmaking nowadays, she says, is not so different from what analog tape has come to mean with music recording.

Jones, too, thinks printmaking is something more and more people are finding themselves interested in. “There’s a real desire to get your hands dirty,” he says, and “a wonderful sharing of ideas.” Due to the fact that printmakers are so heavily reliant on communal workspaces, the result is “a community that revolves around the locus of the print shop.”

Today, most of Chicago’s presses are heavily concentrated on the North Side. There is Spudnik Press, off Hubbard—where Born has worked and taught classes—and also the Chicago Printmakers Collaborative, in Ravenswood.

On the South Side, until recently, the Southside Hub of Production (SHoP) had a printmaking studio but lost its space. SHoP head Laura Schaeffer says that the organization is looking into having one again. “If we had space,” she says, “we’d like to have a kind of DIY community print shop.”

Not far from SHoP’s former location, the Hyde Park Art Center offers printmaking classes and is currently showing an exhibition titled “Oli Watt: Here Comes a Regular” that spans the career of another Chicago printmaker.

Back in 1966, a series of exhibitions at the Hyde Park Art Center inspied a group of artists to call itself the Hairy Who. The group is considered a part of the larger Chicago Imagist movement, which developed in reaction to the New York art scene of the 1960s.

Born, who had a stint at Bard College in New York before transferring to SAIC, recalls attending a retrospective exhibition of one of the Hairy Who’s early members, Karl Wirsum, while in high school. Wirsum was known for his inventive, large-scale prints.

“It blew me away, and that’s part of the reason I decided to study at the School of the Art Institute,” she says of the exhibit. “I took Karl’s drawing class for three consecutive semesters.”

“The Imagists were working at a time when it wasn’t necessarily in vogue to paint recognizable things,” Born says. “Abstract Expressionism in New York still dominated when the members of the Hairy Who were in school. It was rebellious to do what they did—and it’s still exciting, fifty years later.”

For Born though, the central draw of printmaking remains its revelatory experience. “I like the process of discovery involved in printmaking,” she says. “The moment that the print is revealed…it’s different from, say, painting, which is an additive process, so there’s not that same surprise.”

When Born and Hoare show me the original images—whether carved on wood or etched on metal—of some of the prints on display, this notion of transfiguration becomes a little clearer. You try to imagine the series of processes of woodcutting, image transferring, and ink layering that took place before the work is finally put through the press. The result is a singular image—often transfixing—formed by these multiple processes.

“Every single process involves some kind of transformation,” Born says. And then, there’s that final reveal of what she calls an epiphany.

“I’m addicted to that feeling,” she says.

Great article! This is such an amazing new art space, I’m really excited to see what the future has in store for Hoofprint.