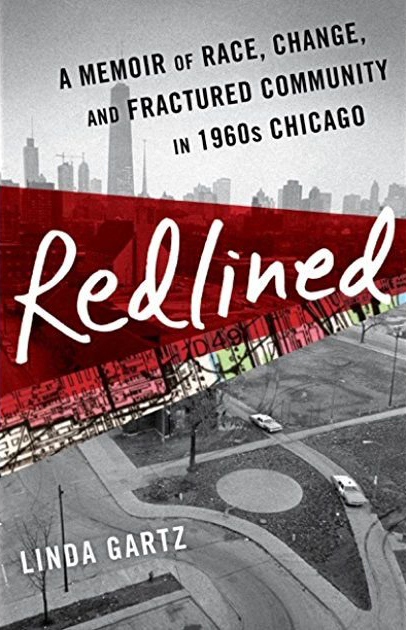

Linda Gartz’s family lived three generations in West Garfield Park, from the time her father was born in 1914, when it “was a neighborhood of wooden sidewalks, dirt streets, and butterflies fluttering above open prairies” to her senior year of high school in 1966. By the time the family moved away, racial riots had destabilized the neighborhood, and white residents were fleeing for the suburbs. Gartz’s new memoir, Redlined, combines recent scholarship on redlining with the intimacy of a treasure trove of diaries her parents kept throughout the years. The result is a compelling chronicle of both a neighborhood’s journey and a personal one, as Gartz pieces together her past and works to place the events of her childhood in historical context.

The memoir’s title refers to the discriminatory practice of denying access to housing based on race, which was prevalent among banks and government agencies that dealt with housing issues in response to the Great Depression. Agencies like the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and Federal Housing Administration (FHA) created color-coded maps to determine the perceived risk of insuring mortgage loans in different neighborhoods, with racially homogeneous white neighborhoods deemed low-risk and colored in green, and neighborhoods with Black residents considered high-risk and colored in red.

The memoir gives readers a front row seat to what it was like when, during the Second Great Migration, the practice of redlining combined with ordinary racism led to remarkable changes in neighborhoods like West Garfield Park. Gartz weaves narratives from her parents’ diary entries and her own recollections together with historical research data to tell the story of the changing city demographic in an engaging, multi-faceted way.

An early indication of coming neighborhood change is documented in a 1953 letter between her parents, Fred and Lilian (Lil). They discussed an observation from a neighbor that within the span of three years, the block on 14th and Pulaski in North Lawndale, two miles south of the family’s home, had changed from majority white to majority Black. Gartz uses census data to show that the demographic of North Lawndale in 1950 had been eighty-seven percent white, a drastic difference from the demographic perceived by their neighbor just three years later.

This news added urgency to her parents’ anxiety over the investment in their home, in which they had placed a great financial stake. To supplement the income Fred made as a traveling fire inspector, the family kept on the previous renters in the first home they purchased in 1948, a two flat located in West Garfield Park that they bought with four years of Lil’s secretarial salary savings. In 1951 they took out a large loan, worth almost half the cost of the home itself, to subdivide the second floor and basement levels in order to take in additional renters. This additional investment meant that the wealth of the family—and their debts—were further tied up in the fate of the neighborhood.

“My parents were undoubtedly clueless about the racist policy of redlining an area when Blacks arrived, but they knew the outcome,” Gartz writes. “If even one African American moved into West Garfield Park, property values would plummet for whites who wanted to sell, threatening the money, sweat, and marital harmony my parents had sacrificed in creating and maintaining our rooming house.”

Unlike her parents, Gartz does not come across as clueless about the racist consequences of redlining in her memoir, pulling from a variety of research, including Richard Rothstein’s acclaimed 2017 book on government-sanctioned residential discrimination, The Color of Law. The book describes how although by the 1930s there already existed integrated neighborhoods across the United States, the practice of redlining reversed this trend and instead spurred the growth of aggressively segregated communities.

Though the FHA was created to help families afford homeownership by insuring mortgage loans and new housing construction, the agency considered insuring homes for Black Americans too financially risky. In the Underwriting Manual, a guide for FHA appraisers, the FHA instructed appraisers to assign less value to property in areas that were not all-white, saying that “important among adverse influences…are infiltration of inharmonious racial or nationality groups.” The manual also encouraged segregation, saying that “all mortgages on properties protected against unfavorable influences, to the extent such protection is possible, will obtain a high rating.” Because bank financing for mortgages and new construction depended on whether the FHA appraised an area as low-risk enough to insure, this led to Black residents not being able to afford housing in new white suburbs, and the rapid depreciation in the value of homes in Black neighborhoods.

As a result, Black workers and families moving to places like Chicago had limited housing options. This segregation allowed Black residents to be easy prey for exploitation, such as substandard municipal services and exorbitant rents. Rothstein references a 1946 magazine article that described a minutely subdivided converted storefront in Chicago where the landlord made as much in rent as a luxury apartment in Gold Coast along Lake Michigan.

Gartz’s parents had also subdivided their two-flat to generate more rent income when the neighborhood was still all-white, but they were conscientious landlords who took pride in providing a well-maintained home for their tenants. Fred’s parents were in the janitorial business all their lives, and they instilled in their children a strong sense of stewardship in taking care of buildings. Gartz relates her parents’ surprise and indignation one time when they learned that a prospective Black tenant kept inquiring about the unit’s heat because her previous apartment lacked it, forcing her to wear coats indoors. “Dad, his parents, and his brothers had awakened in the middle of the night to keep their coal-burning furnaces functioning perfectly,” Gartz writes. “He said, ‘I guess that’s how these other landlords make a killing—just don’t heat the place!’”

Despite her parents’ sense of responsibility as landlords, Gartz is clear-eyed about her parents’ racism during the tense period prior to the first Black family moving to their block. She doesn’t shy away from describing the ways in which, as homeowners and as landlords, they participated in discrimination against potential Black residents.

Worried about giving their neighbors the impression that they would be the first to “break the neighborhood”—that is, sell or rent to a Black family—Fred and Lil went so far as to forbid their daughter from inviting her grade school friend Stephanie, who was Black, to a birthday party in case the neighbors saw and drew the wrong conclusion. Gartz writes movingly about skipping over Stephanie when handing out invitations in class: “[Stephanie] held my eyes with clear and bitter understanding as I passed her desk. She said, ‘You only invite those little curly-haired girls, don’t you?’ […] Nothing I said could undo the insult.”

The family also tried to screen out potential Black tenants by writing classified ads aimed at white renters, which were rejected by the newspaper company for seeming discriminatory. Gartz recalls once early on asking why her mother had turned away a Black renter at the door: “Very matter-of-factly, Mom gazed down at me and explained, ‘Linda, we can’t rent to colored. If we did, then the whole neighborhood would go colored, and we would lose our house. This is how we make a living.’”

Gartz doesn’t excuse her parents’ discriminatory actions, but she tries to put them into context by describing the volatility of the era, when “it took only a rumor of African Americans entering a neighborhood to spawn a white riot.” She says that the effects of redlining “exacerbated whites’ racism and maintained segregation of the races, creating a vicious cycle of stereotyping.” As a result of the FHA refusing to insure mortgages in integrated neighborhoods, the housing stock of those neighborhoods plummeted, which in turn fed into the widely held perception that Black residents were bad for a neighborhood’s housing prices—the rationale that the FHA used to justify their policies in the first place. It was a self-perpetuating cycle.

It didn’t help that speculators took advantage of the situation, scaring white homeowners who lived on the border of white and Black neighborhoods into selling their homes below their worth, then turning around and selling to Black families at an inflated rate. These methods, called blockbusting, involved tactics such as hiring Black women to push baby carriages through the neighborhood or hiring Black men to knock on doors and ask whether homes were for sale. Gartz recalls that on her family’s block, they found flyers urging “GET OUT BEFORE IT’S TOO LATE!”, and neighbors received phone calls in the middle of that night that only said, “They’re coming,” before hanging up.

Her parents knew that these were scare tactics, but they were often torn about whether to move out of the neighborhood before it declined in value. Gartz negotiates the fraught balancing act between sympathizing with her parents’ unenviable position and pointing out her family’s privileged situation from which Black families were excluded. Their budget was tight, but the family still owned three properties as landlords, one of which was a $40,000 gift from Fred’s parents. They could afford to enroll their daughter at Luther High School North, away from the distraction of gangs and overcrowding, and they had enough money and the option to move out of West Garfield Park and to a new, welcoming community if they chose.

“African American couples had the same dream,” Gartz points out. “They, too, scrimped and saved to buy homes in good neighborhoods. They, too, wanted to own property, wanted their children to attend uncrowded schools. But while whites could live wherever they chose, Blacks were vilified and terrorized out of white areas. They were denied mortgages and therefore the ability to build wealth from homeownership—as white families could.”

Memoirs are always a sentimental undertaking, and, despite the title, this memoir is more of an account of Gartz’s family’s life during her coming of age than an analysis of redlining. A lot of pages are spent detailing the specifics of her grandmother’s mental illness and the deterioration of her parents’ marriage, which may not be of interest to those seeking an insider account of housing discrimination. But the personal family history, which Gartz shares with unwavering honesty, serves as an important reminder of how easy it is for people to perpetuate a great societal injustice simply by protecting their own self-interest.

The Gartz family moved out of West Garfield Park in 1966, well after the last white neighbors they knew had moved out of the neighborhood, adding one more family to the widening segregation in Chicago. The consequences of redlining are as present today as ever. A recent study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition showed that neighborhoods originally redlined by the HOLC and the FHA are now, eighty years later, much more likely to have low-income, minority populations. Redlined isn’t a book that suggests policy changes or solutions, but it is a step forward, showing that the need to understand and fix the problems of segregation isn’t just something done for others. As Rothstein writes, “we, all of us, owe this to ourselves.”

Linda Gartz will give a book talk on Redlined on June 24 at 57th Street Books, 1301 E. 57th St.

Tammy Xu is a contributor to the Weekly. She grew up in Naperville and works as a software programmer. She last wrote for the Weekly about “A Tender Power: A Black Womanist Visual Manifesto,” an exhibition at Rootwork Gallery, in April.

Dear Tammy,

Thank you for this very detailed and carefully written review of my memoir, “Redlined.” I appreciate your close reading of my book, the helpful comments you added based on your own knowledge of redlining, and the consequences of redlining, which our nation still lives with today.

As you mention, my memoir is not an academic book on the subject. My website’s “book” page (drop-down menu: resources) lists many excellent academic books (as well as articles and videos) if one wishes to learn all the historical and policy details of the history and impact of redlining.

For those readers who prefer a story to an academic book, “Redlined provides the basics of the insidious practice of redlining told from the point of view of a family (as recorded in letters and diaries) who stayed to witness and suffer the consequences. That’s what make “Redlined” unique.

My parents stuck with the community for more than thirty years after the first blacks moved onto our block in June 1963. (Although the family moved north in 1966, my parents continued to travel to West Garfield Park to care for their three buildings until 1983, and for the two flat in which I grew up until my mom’s death in 1994.)

As you point out, I was scrupulously honest about my family and the era. It’s a universal story of the forces that can undo a relationship, the impact of mental illness on families (an issue for many families today), and the coming of age of a young girl in a tumultuous time.

Thank you again for a thorough, finely written review.