On the south lakefront, a series of art installations has transformed open park space into gathering spaces. Through this initiative, Roots and Routes (R&R)—a network of major institutions and South Side community organizations working to break down barriers and connect people, especially communities of color, to local green spaces—hope to open up an opportunity for residents to explore a new form of urban green space.

Along with community organizations in Bronzeville, Chinatown, and Pilsen, the Chicago Park District and the Field Museum worked with local artists to co-curate art installations depicting the ecological and cultural significances of their communities. The sites for the gathering spaces that resulted were placed strategically along the wood chip paths that weave in and out of the newly restored natural areas of the Burnham Wildlife Corridor (BWC). These gathering spaces are intended to help residents engage with the new natural areas by inviting them to participate in the decision-making and implementation processes and encouraging cross-cultural community engagement through a series of events and ecological stewardship programming.

Last year, to see how well the Roots & Routes Initiative was meeting its goals, and to what extent nearby residents were engaging with these new meeting spaces, I collected data with a social science team through the Urban Ecology Field Lab (UEFL), a program run by the Field Museum’s Keller Science Action Center that allows students to conduct their own research projects. To get a better sense of who was using the BWC, and for what reasons, we conducted surveys to assess the accessibility of these spaces, and people’s motivations for using them.

Our data revealed that a large number of people who visited the BWC were completely unaware of the existence of the gathering spaces; however almost all of those surveyed expressed an interest and willingness (and in some cases, even eagerness) to visit after being told about the project and shown pictures of each site. Descriptors such as “serenity,” “tranquility,” and “relaxation” came up frequently in our analysis of approximately sixty surveys. This helped my research team understand that residents often turn to parks and being in the outdoors as an opportunity to unwind and get away from the stressful bustle of city life.

Which led us to the question: how do we get these gathering sites, many of which are tucked away from the main lakefront trail, on the radar of the people they were designed for?

Aasia Mohammad Castañeda, the Community Environmental Engagement Coordinator of the Field Museum’s Science Action Center, found that presenting a user guide map for the gathering spaces as a scavenger hunt, elicited a more positive response and greater interest from people, especially those with children. These encounters, as well as my own experience observing the Morton Arboretum’s “Troll Hunt,” which also uses a scavenger hunt format, led us to believe that a scavenger hunt would be the most approachable format. A scavenger hunt opens up the opportunity for kids to explore urban nature through an unstructured, sensory activity; to help foster a positive relationship with nature; and to develop survival skills like map-reading—as well as for adults interested in channeling their inner Indiana Jones.

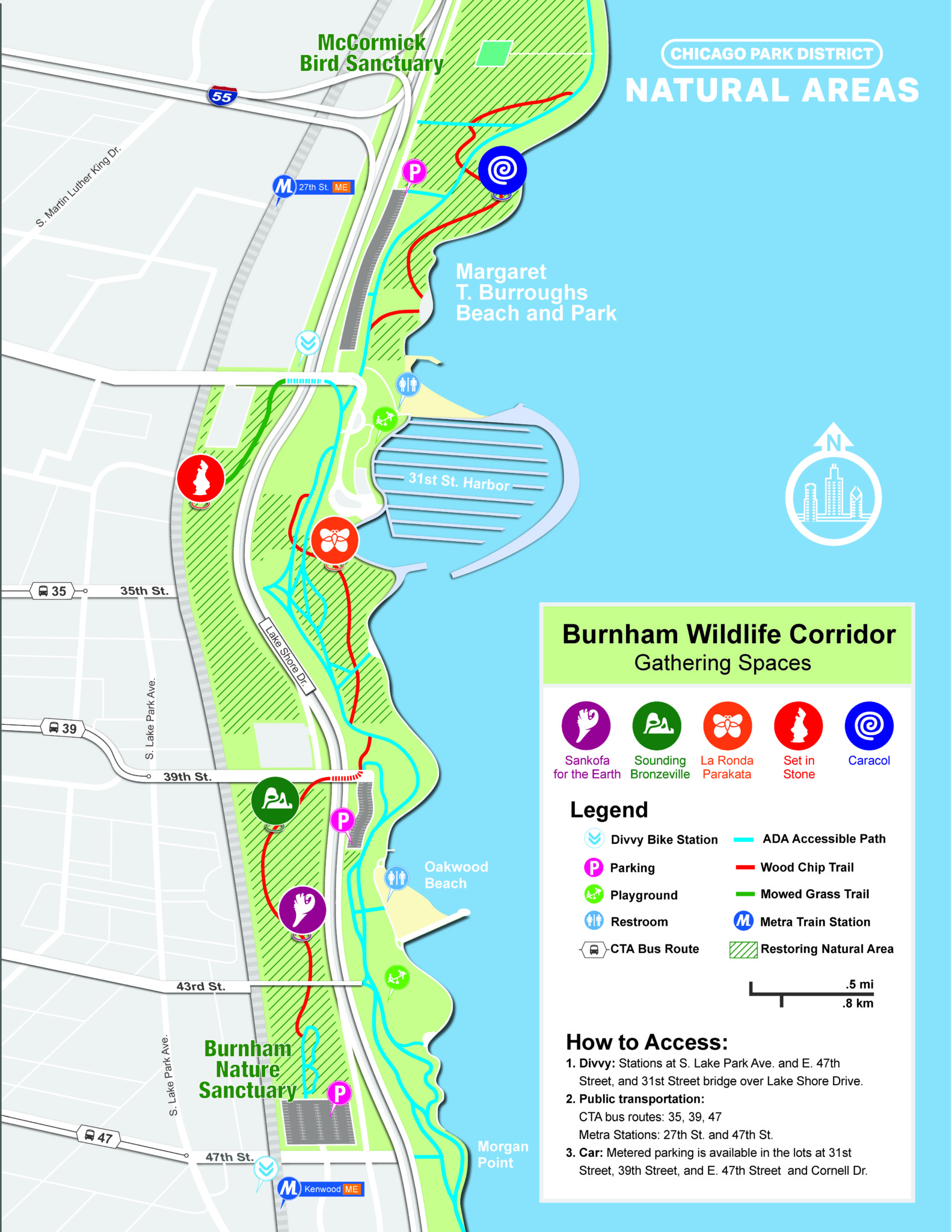

We designed a user guide for the gathering spaces with a scavenger hunt in mind. Of course, no scavenger hunt is complete without a map. The newly developed BWC user guide contains sections explaining the Roots & Routes initiative, and ideas for how users can explore during their visit to the BWC. Further unfolding of the guide reveals a BWC Map, which indicates the locations not only of the gathering spaces, but also of ADA-accessible, wood chip, and bike trails, and amenities such as parking lots, playgrounds, and Divvy bike stations.

As an extension of my research with UEFL in 2017, I returned as the R&R’s intern this past summer to help test how well the user guide works as a tool for navigation and engagement for park users exploring the BWC. In order to do this, I conducted a focus group with participants from the UIC Center for Literacy’s South King Community Service Center, to see if our approach would, in fact, be more interactive and fun for park users, and whether it would ultimately work to recruit new and returning BWC park users to engage with the Gathering Spaces.

We asked questions to get a sense of how accurately the map reflected the actual landscape, how the existing signage assisted in navigating the BWC, and what wayfinding improvements can be made to enhance the user’s experience. This focus group revealed a number of unexpected findings. For instance, one participant who had her two young children accompany her on the hunt, said she would be more interested in seeing additional signage for on-the-ground wayfinding as well as interactive signage about the ecology of the BWC and stories of the gathering spaces. It was also brought to our attention that the “In Progress…” signs located along the the BWC might communicate to visitors, especially those unfamiliar with the new natural areas, that this area is restricted—either off-limits to the public or not yet ready for people to enter. This led us to believe that the issue with connecting people to the gathering spaces through the natural areas was not just a lack of signage, but also the type of signage. Our participants suggested that we make the language more inviting. R&R will use this feedback as it plans for future signage.

With its prairie restoration projects, the Burnham Wildlife Corridor is helping to break down the long-standing notion of nature as a fenced-off, non-social, protected destination. The gathering spaces present an opportunity for residents to engage with this new form of urban nature coming to existence in our city, but we need research from the UEFL and the Field Museum’s Science Action Center to understand how these initiatives are being received by the public. Transforming Chicago’s south lakefront into an urban green space with ecological conservation and community engagement through art can provide residents a sense of belonging and empowerment. Now, with research and active community programming to bring communities together at these sanctuary sites in the BWC, R&R’s initiative is working to make this vision become a reality.

Diana recently graduated from Roosevelt University with a double-major in sustainability studies and sociology, and in the time since has worked on projects ranging from stewarding RU’s rooftop gardens, completing an environmental science research fellowship, running logistics for One Earth Film Festival, and volunteering with The Field Museum’s Youth Conservation Action field trips. She is committed to directing her passions for environmental and social justice toward building resilient initiatives in her home community of Berwyn.

Very well written and informative article! The research was synthesized well and explained thoroughly. The passion and dedication for her work really shows. It inspires me to get more involved with my community in a green sense.

An outstanding article that illustrates the value of urban nature within the landscape of the city as well as the need for understanding how people interact with the features of the urban environment. Diana’s articles shows us how Chicago is both a natural and human ecosystem, one constantly under construction (and now, restoration).