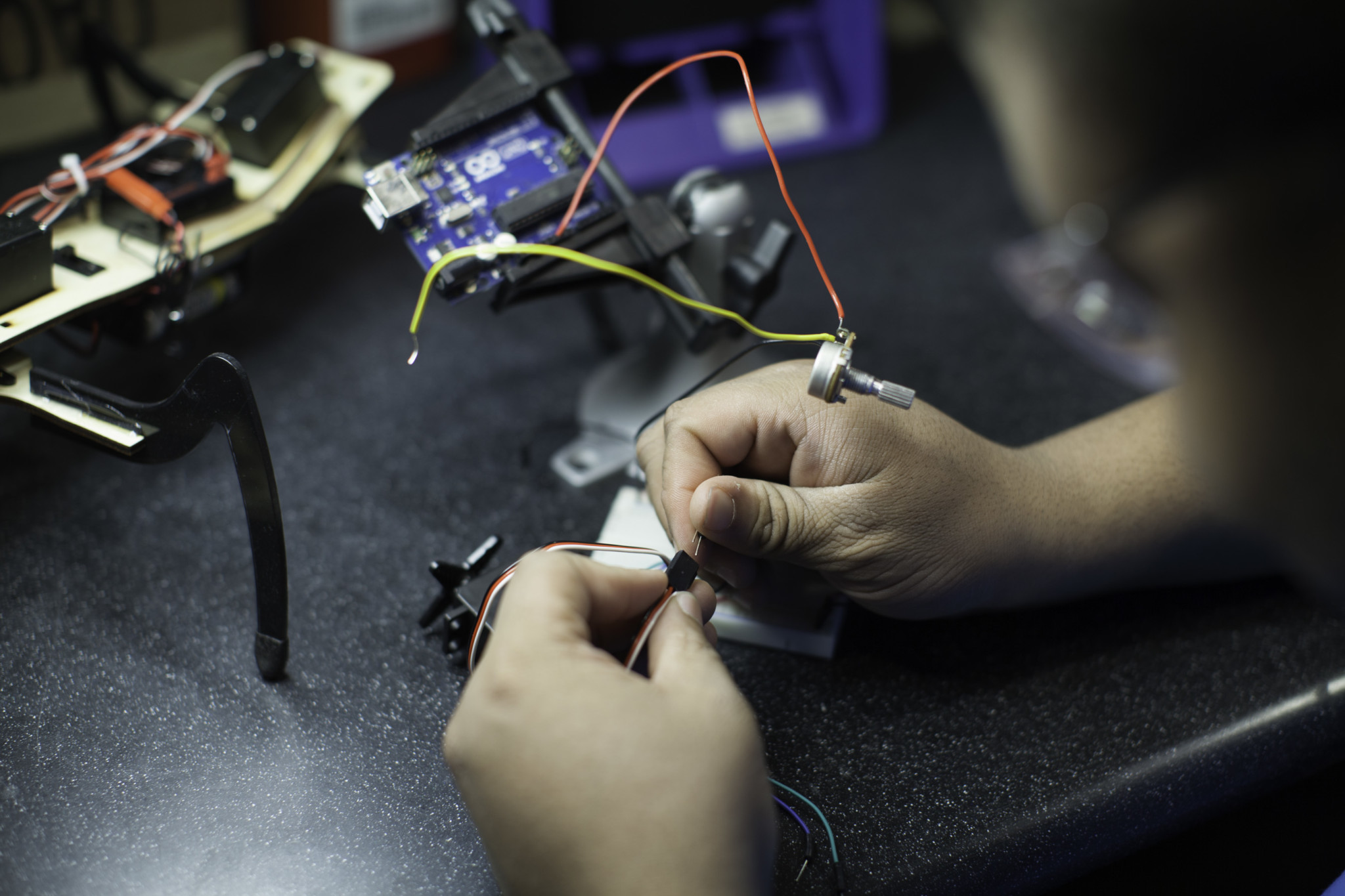

The weekly member meeting of the South Side Hackerspace (SSH) begins with a call to those in the room to “gather around the TV.” The TV in question is facedown on a table with its back wide open and its internal hardware exposed. It’s the electronic centerpiece of a table cluttered with wires and circuitry.

“That’s not what most people mean when they say ‘let’s sit around the TV,” said the man tinkering with its wires, “but we do things a little differently at South Side Hackerspace.”

SSH, located in Bridgeport, is one node in a citywide network of spaces for “makers,” amateur craftspeople who work on personal creative projects with a variety of materials ranging from wood to wire. For a fee, these spaces allow makers to use communal tools and equipment, attend workshops on crafting techniques, and learn from each other as they build.

The meeting at SSH starts with introductions; each person present says their name and affiliation with the space, many adding a “by day I am” before stating their occupations. Most members hold day jobs working with computers or technology in some form, with just one man reluctantly admitting to a standard office job, an embarrassing truth in a culture centered around working with your hands.

The space is entirely volunteer-run: no one profits from its existence, including “the board,” a group of seven members elected by the larger member base of around thirty. This emphasis on community operation is a big part of the hacker ethos—the facilities and equipment of each space like this are a direct reflection of the desires, interests, and contributions of its members.

“Any new equipment we get or thing we add is a result of somebody thinking, ‘I want there to be something here, nobody really disagrees with there being something here, this is a positive change to make, and I’m not moving anyone else’s things that were here to put something here,’” said Christopher Agocs, the space’s member-at-large. Agocs is the board member responsible for representing the needs and concerns of the member base. Much of SSH’s equipment is used, donated, or belongs to individual members who leave it in the space to share with everyone. The downside of this is that when things break, they don’t often get fixed quickly.

“The laser cutter’s power supply was down for months because no one had the funds or desire to get another one,” said Agocs, “and it only got fixed when one member was like, ‘Oh, this is pretty easy, I’m just going to buy a new power supply’.”

The growth of the space reflects this ethos—it has often progressed randomly rather than in a singular direction. Agocs says that when new members come on, “we try to be very upfront about the fact that just because we have these things now doesn’t mean they’ll always work, and doesn’t mean that in six months everything might not be completely different.”

SSH’s lack of stability is not suitable for every maker, nor is its focus on work with electronics. Luckily, those who want a space to work on hands-on projects without all the responsibility of shaping an organization will find exactly that at MAKE! Chicago, a “makerspace” founded by Joseph Budka and located in the same building as SSH.

While makerspaces and hackerspaces share the same goal of getting people excited about working with one’s hands, they differ in their approach to leadership. Unlike a hackspace, makerspaces are typically run in a hierarchical structure, with a select number of people making decisions about the future and direction of the space.

“Ten years ago, people would finish up art or trade school and then have to spend thousands of dollars on equipment just to start making stuff,” said Budka. When he heard about the makerspace movement, he realized that he was already doing a very similar thing by sharing his equipment and space with studio-mates. He decided to “rebrand and start running a makerspace with a capital ‘M.’

At MAKE!, $150 a month will get someone twenty-four-seven access to a wide variety of wood- and metal-working tools, a space to work on large projects, and a community of people to learn and collaborate with. “Camaraderie is a healthy thing—some people go to a knitting circle, some people come and build furniture,” Budka jokes.

MAKE! is a unique makerspace because of its commitment to focusing primarily on woodworking and metal fabrication. Budka sees it as “filling a very specific niche—people come to us who are artists, retirees who want something to keep their minds and hands active, and people who want to work on wood or metal projects but don’t have the space for it at home.”

MAKE!’s website boasts “hundreds of tools!—Chop saws, table saw with multiple blades and dado set, Grizzly 20” industrial planer, several scroll saws, spindle sander, disc sander, lathe, band saws, drills, drill press, circular saws, jig saw, reciprocating saw (lots of saws), belt sanders, orbital sanders, palm sanders, MIG welder, oxy-acetylene torches, clamps, metal chop saw, angle grinder, etc.”

Budka is the sole proprietor of the space and has big dreams about MAKE!’s future: he soon hopes to move into his own building and expand into digital fabrication and sewing.

Although the makerspace movement has grown in popularity over the past few years, individuals like Dan Meyer, the manager of the Wanger Family Fab Lab at the Museum of Science and Industry (MSI), have been involved in Chicago’s making movement for years. A fab lab, such as the one Meyer runs out of the MSI, is a makerspace with a more academic bent. The trend originated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2003; fab labs now number at over one thousand globally. Every fab lab has a set of standardized equipment, and is constantly in communication with the others about how to best serve the educational needs of each space’s audience.

MSI’s Fab Lab caters primarily towards are museum guests and students. There are hour-long ticketed workshops that run every day, and similar programs targeted at Chicago-area students. The fab lab works with schools who do not currently have the capabilities to provide engineering, machinery, or design programs, and help them build up their own makerspaces back in school, or at least think of ways they can use what materials they do have in creative, maker-oriented ways.

“You don’t always need all of this equipment; you could just use what you already have at the school, which sometimes is just a set of computers and regular paper printers, and you can do a lot of work with that,” Meyer said. “You can learn digital design, print out a pattern on a regular paper printer and trace that onto a piece of cardboard or foam to make something in 3D.”

The workshops held at the Wanger Family Fab Lab introduce thousands to “making” every year, influencing them to join other makers spaces throughout the city. Meyer describes the maker and hacker scenes both throughout Chicago, specifically those on the South Side, as a sort of “ecosystem,” with each space serving a specific role for its members. The employees and members all know each other, often moving throughout the network. Meyer himself spends his evenings and weekends teaching classes and working on his own projects at the two hackerspaces he’s a member of, while also helping direct newcomers to the spaces that will best serve their needs and interests.

“If you want to do woodworking you go to MAKE! Chicago and see Joe [Budka], and if you wanted to get access to 3D printers 24/7 you go to South Side Hackerspace,” said Meyer. “And if you want to learn how to get into all of this, then you come to our space and get a really quick introduction and then move on to the other spaces.”

Once one enters the network, there’s no telling where their path might lead and what types of skills and knowledge they might accumulate along the way—that freedom is part of the joy of the community. While different spaces focus on working with different materials, nearly all individuals at any of the spaces cite the agency involved in the making process as the best part of being involved in the community.

Acquiring these skills means developing the power to disrupt one’s cycle of consumption, which Dan Meyer views as a very exciting prospect in such a readymade, consumer-oriented culture.

“We have these industrial machines where ‘things’ are produced and manufactured, and normally we never see them—they’re run by technicians and machinists—and …our idea is that we can do this as individuals,” he says. “Anyone can design and make their own things.”

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

Thank you so much for featuring us. This is a superbly written article and we are really grateful to have been included. We are also very excited to announce that we are now over 50 members! All the best, from us at South Side Hackerspace. 🙂