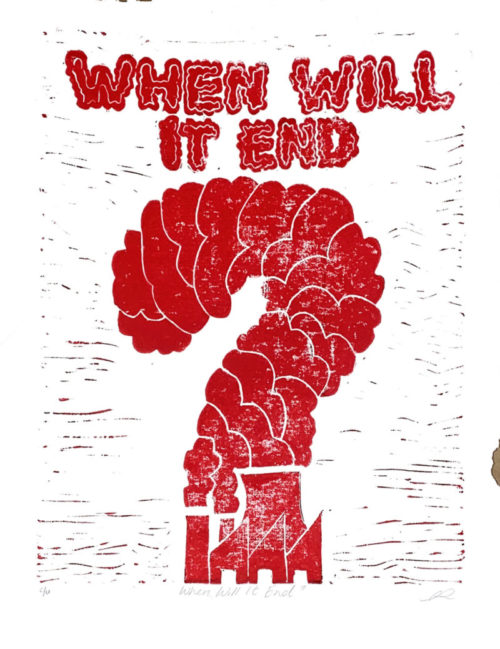

This piece is part of a series that explores the various perspectives around defunding the police.

The Southeast Side community on the Calumet River has historically been an industrial corridor. The longtime home of the old steel mills has recently become the city’s designated dumping zone, and residents struggle with exposure to petcoke, manganese, and landfills. The area is eighty percent Mexican and has been making headlines lately due to the current struggle to stop General Iron Industries from relocating their metal recycling facility from a North Side neighborhood. And one of its high schools, George Washington High School, voted 6-5 to remove the School Resource Officers (SROs) as part of the citywide movement to get Chicago Police Department (CPD) officers out of the Chicago Public School (CPS).

While on the face of it, these two struggles may not seem to have an obvious connection to one another, to many members of the community they are two sides of the same coin. To many in the Southeast Side the current $33 million contract that was just approved between CPS and CPD and the failure of elected officials to step in and deny the permit that would allow a notorious polluter to move in highlight the lack of prioritization of the needs of the people living furthest from downtown.

“Throughout the eighteen years that I have lived in the Southeast Side of Chicago, I cannot remember a single year where I have not smelled the stench coming from some of the factories around the neighborhood,” said Washington alum Liliana Muñoz at a forum hosted by the Chicago Teachers Union Climate Justice Committee in July.

It’s hard to ignore the racial component when it comes to the question where exactly the city decides to locate polluters. The General Iron metal scrapping facility slated to be relocated to the neighborhood would be operating less than a mile away from the high school and, based on the wind trajectory in the area, the brunt of the particulate matter emitted from the facility would be blown in the direct path of the school.

“I definitely fear for my health and safety from being exposed to high numbers of dangerous chemicals,” said Lauren Bianchi, social studies teacher at Washington. “But as a teacher that doesn’t live in the community, I’m most concerned about the health and safety of my students and coworkers that live in the area. This neighborhood has a high number of health problems.”

“We already have a high number of students that have asthma, have dealt with cancer in their families,” Bianchi continued. “I fear that my students won’t be able to learn due to health issues, things like asthma attacks would obviously disrupt learning.”

There’s another threat to the immediate safety of Washington students. Although Black students only make up about five percent of the high school’s population, they’ve faced a disproportionate amount of harassment at the hands of the school SROs.

The current struggle to get CPD out of CPS is part of the largest civil rights movement we have seen in a generation. The ongoing Black Lives Matter movement has called for police departments to be defunded and for those funds to be invested back into marginalized communities. Among many other demands have called for police officers to be removed from public schools. According to the CopsOutCPS Report, despite only making up about thirty-six percent of the entire student population, Black students are subjected to police notifications at four times the rate of white students in Chicago. Furthermore, more than ninety-five percent of police incidents in CPS have involved students of color.

“We’re creating a hostile, unsafe environment for our Black peers by allowing CPD to constantly criminalize them,” wrote LSC student representative Trinity Colon in The Triibe. “Too often our community only focuses on issues that affect Latinos, and these are serious, valid issues that need to be addressed. However, we need to keep that same energy when it comes to the injustices occurring within other marginalized groups of people. We must strive to protect and value all of our students; we can’t cherry-pick which minority groups we’re going to fight for.”

The infrastructure that made it possible for students to mobilize to have the Local School Council (LSC) vote go their way actually began somewhat at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Teachers and staff at Washington set up a mutual aid fund, similarly to what a few other schools in Chicago did. The mutual aid project brought teachers together with members in the community and made it possible to expand outreach beyond their immediate networks.

Through virtual means, teachers met with student leaders, including the Students Voice Committee and the Black Student Alliance, to share data on SROs once it became known that the CPS school board was about to discuss the current contract. The youth-led Black and Brown solidarity actions that occurred earlier in the summer at the start of the ongoing uprising against police brutality showed many that attitudes in the neighborhood were changing in a progressive way.

The other key factor was being able to position Washington students as leaders in those talks. After being introduced to the issue, the students felt strongly about the pattern of discrimination and took the lead from there. “We aren’t protecting and caring for our Black students, and that’s a problem,” said the high school junior. “Not only is racism a clear factor in this discussion, but with it comes serious adultism. Adults are refusing to acknowledge the voices of young Black and Brown people when we say how having CPD in schools makes us feel unsafe and afraid. It doesn’t matter if we’re calm and collected or if we’re screaming from the top of our lungs: they dismiss what we’re saying because of their ideals.”

The response by teachers like Washington science teacher Chuck Stark made it possible for students to raise their voice and have their agency be taken seriously by the status quo by challenging the notion of “adultism,” as Colon wrote. “If we want to prepare students for the real world, I don’t want my students walking out to a system that takes advantage of them,” said Stark. “I want them to challenge that system.”

The vote to withdraw the SROs out of the school successfully removes the threat of what some teachers called “armed surveillance” patrolling the lunch room with guns in hand, in a setting which should be a place of safety for students.

Just as data revealed that SROs were disproportionately disciplining students of color, data shows that the emissions that would come out of a new metal shredding facility would be harmful to the health of everyone residing or working in the area. Considering the current health crisis, any additional emissions would be further devastating to the community.

East siders have recently announced the filing of a civil rights complaint against the City of Chicago’s zoning policies, alleging that their history of relocating industrial facilities have been deepening housing segregation and racial discrimination in the area.

“According to the permit they are not breaking any rules,” said Stark. “They fall within those legal limits allowed by the EPA. They are releasing particulate matter that the EPA themselves admit is harmful to your health, but they are still allowing it. Yet another fire has to be put out.”

The energy and passion in the neighborhood is there. But to cultivate the type of push needed to move Mayor Lori Lightfoot and City Council to step in and stop General Iron, the entire City of Chicago may need to demand that elected officials and industrial polluters stop treating the community in the Southeast Side as disposable.

One of these elected officials is 10th Ward Alderwoman Sue Sadlowski Garza, a former Chicago Teachers Union member who during her most recent campaign promised that the Southeast Side would no longer be the city’s dumping ground. However, she has failed to come out in strong opposition of the relocation of General Iron, and in some instances has even endorsed it.

“In getting CPD out of CPS,” said Bianchi, “I want us to reimagine what schools look like. Schools are one of the main places racism manifests, in an extremely racist society. They should not just be a place you learn about this, but also where you learn to challenge that. Schools should be where you fight for freedom.”

By the same token, stopping General Iron can lead to a new vision of what the Southeast Side could be for the folks in the community. Community members want to see broad action taken to regulate industrial facilities. They want the city to question the zoning that allows for neighborhoods of color to bear the brunt of pollution.

Defeating General Iron could also lead to more collaboration between different marginalized communities involved in fighting racism and environmental injustice, such as the CTU-organized forum connecting the General Iron fight to the struggle against the MAT asphalt plant in McKinley Park, and the struggle in Little Village against Hilco, the company responsible for the botched demolition of the Crawford coal plant that covered the neighborhood in ash and dust.

Reinvesting the money from the SROs program back into public schools could go a long way to ensuring that working-class Black and brown kids have the same access to a quality public education that kids in affluent neighborhoods have. The entire CPD budget is $1.65 billion; by defunding the police department funds could be used to offer health care and medical assistance to neighborhoods that have been disproportionately exposed to high rates of pollution and now have adversely suffered from the health repercussions of it. The money could also be used to fully fund environmental protections and programs—such as hiring more inspectors, requiring community input on new permits, or reinstating the city’s Department of the Environment—to make sure industries are operating safely, and with a goal to fully divest from harmful fossil fuels and other dirty industries.

The battle to stop General Iron, much like the battle to remove SROs from CPS, needs to be won in the citywide battle for public opinion. East Side residents have been told that their community would never be the Riverwalk, but that doesn’t mean that the people of that neighborhood don’t deserve substantially better than what the city has offered them for decades. Both movements are rooted in the reimagination of what the Southeast Side could look like if the safety and the future of the residents were prioritized by City Hall.

Carlos Enriquez is an activist involved in the campaign to Democratize ComEd and has done consulting for the Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke. This is his first contribution to the Weekly.