When Mitzi Haynes’ daughter Taylor moved back to Chicago in 2017, escalating rents forced her to move in with Haynes and Haynes’ mother in a cramped two-bedroom apartment in South Shore. “It’s going okay, for now,” Haynes said. “But the main problem’s lack of space.”

A year before her daughter’s return, Haynes listened with cautious optimism as the Obama Foundation announced its partnership with the city and the University of Chicago to build the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) in Jackson Park, a few minutes’ drive north from her apartment.

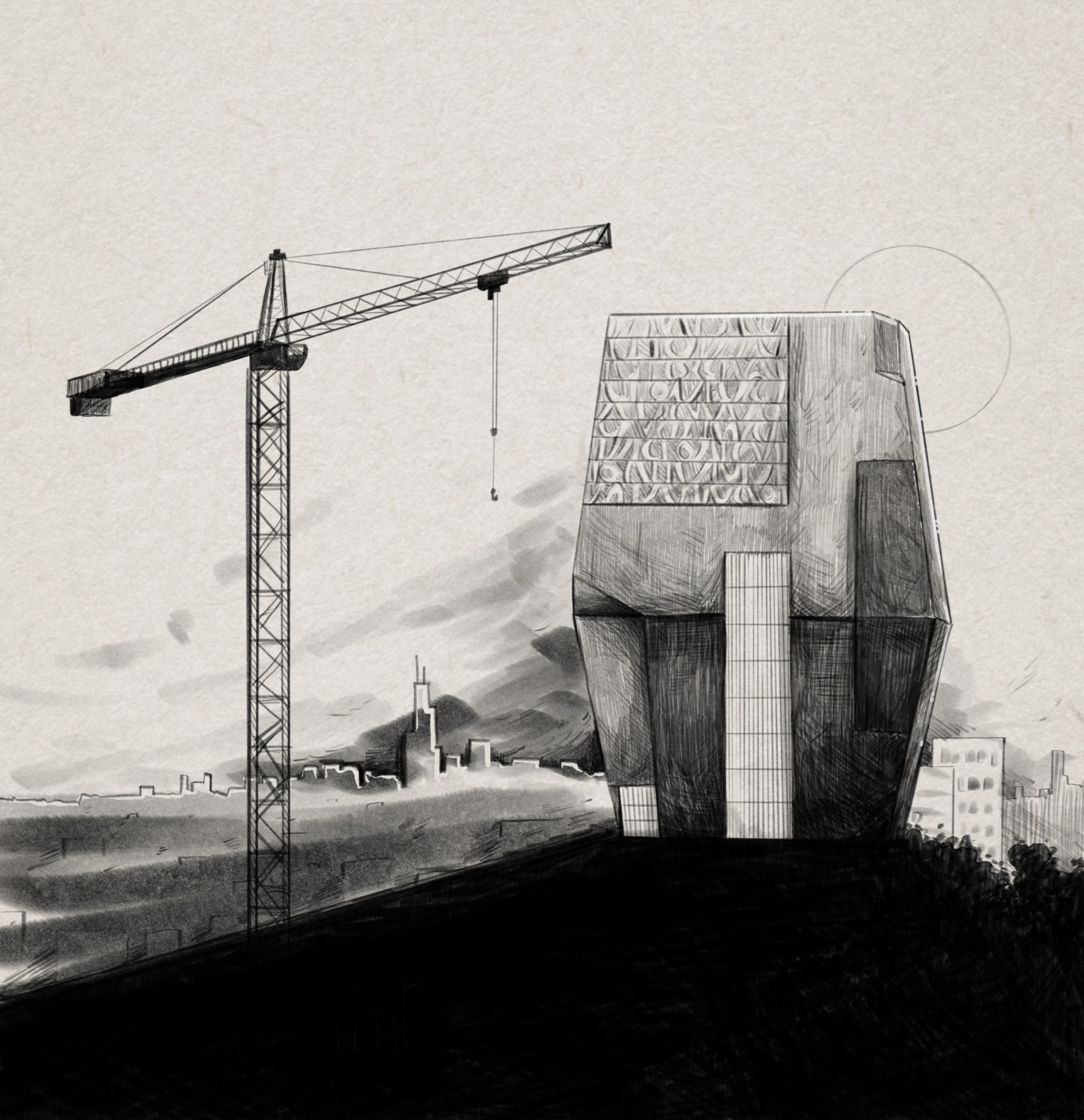

In the vision presented by the city and the foundation, the OPC would be a sprawling complex, replete with athletic facilities, open-air gathering spaces, Obama’s Presidential Library—and a museum, whose design, as the foundation’s website proclaims, “embodies the idea of ascension.”

President Obama and his surrogates pledged that the OPC would not displace longtime South Side residents, and tendered lofty promises of job creation and economic development for Woodlawn and South Shore—the historically disinvested neighborhoods surrounding the OPC. Haynes wanted to believe.

But by the time her daughter returned to Chicago a year after the announcement, Haynes’ hope that those promises would be kept had evaporated.

“As time went on,” she said, “with the rising rent, yeah. That, to me, did not ring true.”

The Haynes family are multigenerational South Side residents. Both Haynes and her mother were born here, and Haynes raised her daughter in Hyde Park. “My family’s considered ‘lifers’,” she notes with pride.

Over the past four years, however, Haynes has watched in alarm as neighbors in her building are priced out of or evicted from their apartments. Haynes’ brother, a fellow lifer and longtime resident of Hyde Park, recently considered moving after the rent on his one-bedroom apartment tripled in the past five years.

After her own rent ballooned by thirty percent in just three years, Haynes, a pharmacy technician, decided to move her and her mother out of the city, before their rent spikes again.

Haynes explained that the magnitude of the Obama family’s celebrity status can cause some to look away from the OPC’s local impact. “He’s the golden boy. You have some people out here, who, doesn’t matter what he does, what he says, he’s still Obama…so he could do no wrong.”

But for her, the OPC’s impact is clear. “To me,” she said, “it’s not for the community.”

The threat of displacement the OPC poses to low-income and working Black families like the Hayneses sparked the formation of the Obama Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) Coalition in 2016.

The coalition, comprising more than twenty organizations from across the city, fought for four years to pass affordable housing legislation for the South Side neighborhoods surrounding the OPC.

Alongside the coalition, 20th Ward Alderwoman Jeanette Taylor proposed a protective housing ordinance in July 2019 that would have mandated that at least thirty percent of units in new developments within two miles of the OPC be made affordable to “very low-income households.” Despite its twenty-eight co-sponsors—including 5th Ward Alderwoman Leslie Hairston, whose ward encompasses the OPC and a sliver of Woodlawn—the proposal never received a vote.

Nearly fourteen months of negotiation ensued, resulting in the momentous passage of the Woodlawn Housing Preservation Ordinance in September 2020.

Shannon Bennett, executive director of the Kenwood-Oakland Community Organization, a founding member of the coalition, says the protections afforded by the ordinance—including reserving thirty percent of units in new developments on city-owned Woodlawn plots as affordable, and creation of a $1.5 million loan fund to rehabilitate vacant Woodlawn buildings—are robust.

Nonetheless, Bennett acknowledges that the ordinance does not go as far as the coalition believes is necessary to protect residents near the OPC.

Specifically, its mandate reserving at least thirty percent of units in new developments as affordable does not extend beyond Woodlawn—an excision from Taylor’s 2019 ordinance wrought from the multiple rounds of acrimonious talks between the city, the Obama Foundation, Taylor, and the coalition.

Meanwhile, the prices of land, for-sale properties, and rent have skyrocketed in all the neighborhoods surrounding Jackson Park since the 2016 announcement.

A 2019 study from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s College of Urban Planning found that in the two-mile radius surrounding the OPC’s planned site, nearly ninety-one percent of renters “cannot afford their monthly rent,” and that “the majority cannot afford” rents in newly renovated and new construction units either.

Within the OPC’s two-mile radius, which primarily includes Black, low-income households, eviction rates are some of the highest in the city, according to the study. In South Shore—not two miles away from where the museum designed to embody ascension will stand—1,800 households, or about nine percent of renters, are evicted annually.

Now, as the coalition fights to secure protections for South Shore and beyond, Bennett said their message remains focused on the needs of families like Haynes’—not on critiquing President Obama, nor sparing him or his foundation accountability.

“We don’t have time to waste in the discussion of ‘well it’s Obama, trust him,’ or ‘he’s the first Black president and you’re trying to stop him,’” said Bennett. “It’s way beyond Obama. We have to focus on saving our lives, our homes.”

The presidential complex is the latest in a long line of sweeping development projects that promise economic growth and housing stability for Chicago’s historically disinvested communities, without grounding those promises in community-informed policy.

In January 2000, then-mayor Richard M. Daley launched the Plan For Transformation (PFT), a $1.6 billion overhaul of Chicago’s public housing system. Under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) pledged to demolish and replace more than 18,000 public housing units, and to relocate those units’ residents into “mixed-income” communities.

The PFT promised to replace the 18,000 demolished or renovated units with 25,000 new or rehabilitated units by 2010. Bennett and his fellow organizers responded by lobbying the city and the CHA for legislation guaranteeing that demolished units would be replaced in real time.

“We fought for one-for-one replacement. Tear down one unit, you replace it with another one, at the same time,” Bennett explains.

The CHA rejected one-for-one replacement. Instead, lease-compliant public housing tenants were offered the right to return to a new or rehabilitated unit when the plan was completed.

Six years after launching the PFT, Daley pitched another colossal project as an economic boon to Chicago’s disinvested communities: he wanted Chicago to host the 2016 Olympics—and to build its centerpiece, a $400 million, 80,000 seat stadium— in Washington Park.

A few miles northeast of what’s now the OPC’s planned site, historically Black, low-income Washington Park was already in the early stages of a housing crisis when the Chicago Olympic Committee set out to realize Daley’s vision in 2007. After years of predatory lending targeting majority-Black and low-income neighborhoods, the U.S. housing market’s collapse in 2007 prompted mass evictions and foreclosures across the South Side.

As Daley wooed private investment to fund Chicago’s Olympic bid, activists leapt to action to protect Washington Park residents from further displacement driven by the rising rent and property taxes sure to follow the stadium’s construction. “One of the first things we said was we want was to have a representative to sit on the committee,” said Cecilia Butler, a longtime Washington Park resident and president of the Washington Park Advisory Council.

Butler was selected in 2007 as the community representative on the Chicago Olympic Committee. After months of community feedback, she brought a twenty-six-point CBA before the committee, outlining policy proposals to ensure that the stadium’s projected economic impact would benefit residents, not price them out of their homes.

Meanwhile, the Olympic Committee faced waning public support for its bid as the financial crisis deepened—and the CHA’s Plan For Transformation was already thousands of units behind on its pledge to construct 25,000 new units for displaced public housing residents.

As foreclosures and evictions mounted in Chicago’s predominantly Black neighborhoods, HUD granted the CHA a ten-year extension—and about $1.4 billion in additional federal funds—to finish “transforming” public housing by 2018 instead.

In 2009, Chicago’s Olympic bid was rejected—to Butler’s relief.

“That was something I was glad we didn’t get,” she said. “Chicago would have been worse off. Or Washington Park would’ve been, anyway.”

Meanwhile, the PFT lagged behind its extended schedule—while those displaced by the initial demolitions were left waiting, their “right to return” only redeemable upon the project’s completion.

By 2017, less than eight percent of the nearly 17,000 households originally included in the PFT were living in mixed-income communities. The rest were left to weather the private rental market—some equipped with a housing voucher, many without.

In 2018, HUD granted the CHA yet another ten-year extension, pledging federal financial support for completion of the project by 2028 instead.

Many of those displaced by the PFT are now Haynes’s neighbors in South Shore.

Mary Pattillo, professor of sociology and African American studies at Northwestern University, said that “the biggest transformation of South Shore in the past twenty years is that it has been a big receiving neighborhood of public housing residents who were displaced from the demolition of Chicago public housing.”

According to Pattillo, displaced residents were drawn to South Shore by its abundance of multi-unit apartment buildings and affordable rents.

But now, just as it has prompted Haynes to leave the city, escalating rent—this time engendered by the OPC—threatens to displace them once again.

The Obama Foundation dismissed community concerns about displacement in 2016, and pledged that the OPC would not push residents out. Bennett said, “We were told, ‘just trust that this will be done in your best interest because it’s Obama.’

“That’s an insult.”

After witnessing the long-term patterns catalyzed by immense development projects like the Olympic bid and the PFT, Bennett does not see the OPC—nor the fight to ameliorate its impacts—as somehow different from the projects that came before it.

“At the core of all of this is that the Obama Center is just like—I’m sorry to minimize it like that—it’s like a planned development for million-dollar condos,” he said.

When asked what specific programs or policies the Obama Foundation had in place to ensure South Side residents would benefit from the OPC’s presence, a spokesperson for the Obama Foundation declined to comment.

Instead, they highlighted in an email the youth mentorship program spearheaded by President Obama years before the OPC landed in Chicago, and wrote that, “we remain committed to supporting the South Side through economic development and leadership programs. When construction begins on the Obama Presidential Center, we will support job growth on the South Side, ensuring opportunities are specifically given to diverse communities.”

[A]s Haynes and her mother prepare to leave South Shore, Haynes’ daughter Taylor, twenty-five, is determined to stay. “Now that I’m back,” she said, “I have no intentions on leaving.”

As Taylor searches for a place she can afford, she is simultaneously running her own catering company, studying psychology at DePaul University, and attending classes at McCormick Theological Seminary in Hyde Park. She plans to pursue her master’s degree in divinity after graduating from DePaul.

Haynes said she’s encouraging Taylor to work and study as hard as she can while she’s young. “I told her, ‘do that now, so when you’re in your thirties, you can ease up a bit.’”

Yet she worries that the toll of relentless work won’t allow her daughter to reap what she’s sown. “She might be too sickly, too broken down, or too old to truly enjoy the fruits of that labor,” Haynes said.

Savannah Brown, twenty-five, an organizer with Black Youth Project 100’s Chicago chapter, says that while she doesn’t believe that South Side communities asked for—or even wanted—the OPC, she is confident they will flourish regardless. “We will make sure that this vision of doing something for the Black community happens,” she said.

Brown lamented that the city touts the economic force of the OPC as a solution to South Side residents’ problems, while chronically underfunding the services Black communities need: “What about mental health? What about education? The fundamentals that are without a doubt needed, especially in Black communities?

“That’s what we’ve been asking for.”

Nonetheless, Brown says the way forward is clear. “Alas, we’ve been given the Obama Center. we’re still going to make sure that we have a thriving Black community that is sustained in the areas that are impacted by this.”

“Because if we don’t,” she added, “who will?”

Michael Murney is a journalist reporting on housing, policing, immigration, and beyond. He is currently pursuing his M.S. in Journalism at Northwestern University. This is the writer’s first piece for the Weekly.

A good article, my thanks. We Do want to build Obama a center, but this Park location is a huge mistake.

Why not build on vacant lots, urban renewal land – like the site of the Plaisance Hotel, at 60th and the Midway? Alternately the West side of King Drive, North of Garfield? This would bring prosperity to those neighborhoods, and expand the Parks. This plan came about due to the U of C, who have wanted to expand into Woodlawn for years. They want to push the working class people out, note the single family homes they built on 63rd St.

Obama should save Jackson Park, move his Center into the City

The people the glorify public housing obviously have never lived in them, they are HORRIBLE and turn many young people into sink-or-swim survivors of gangs, crime and other unspeakable concerns. I am glad they are GONE!!!

This was a setup from its inception. Michael Reese was the perfect place for the Obama foundation. But the UofC and support by the developers including the Obamas who have no intention of returning here, won out for their own vision which does not included the current people in the south side community. The golf course is just another link in the take over of the south side lake shore. What has happened to South Loop and Bronzeville is now in hyde park, (53rd street) and taking over South Shore

While I’m glad the City Council passed their Community Benefits Agreement, I find it curious there has been no agreement between the Obama Foundation and the Community. What about the jobs that will result? We know there will be an effort to train, create construction jobs; these jobs end when the center is complete. Take a look at the (highly) paid officials at the foundation, such as Robbin Cohen, making over 860k in one year. Realistically, how many jobs will be created, and will they make an effort to hire, from the community? Can they put something in writing, such as their own CBA?

These compromised guarantees are distressing, considering the UofC has an $8 billion dollar endowment is considerably more than 300% of the poverty rate, and should disqualify welfare payments of free public land.

Since the 1.6.21 Insurrection at the Capitol Building, i,m more concerned that the Center is a target for racists terrorists. I don,t think it,s proper to turn public land into a high security private enterprise. Will there be a tRumpian Wall? Humvees with National Guardsmen? Metal detectors, facial recognition software? How much CPD overtime will be sapped from bloated budgets?

No, i don,t think the OPC should be allowed on public land until there is an Obama Beer Summit with the Proud Boys, Oathkeepers, and other white supremacist organizations, to justify public investment.