In a time where we are reassessing what and who in our history should be memorialized, and just whose interests monuments serve, what might the future of monumental art look like? What is considered a monument? The national Monumental Tour attempts to offer some answers.

“For me, the way that I understood the Monumental Tour is that if the whole nation is in this conversation about ‘let’s tear down these toxic monuments’, and then you have people that are resisting that are saying, ‘well, what are you putting in its place?’ What are you talking about?” said Eileen Rhodes, of Blanc Gallery in Bronzeville.

“And so to just step out of the white gaze and go into what is the alternative, these are Black monuments made by Black creators located in Black spaces that have been curated by Black people.”

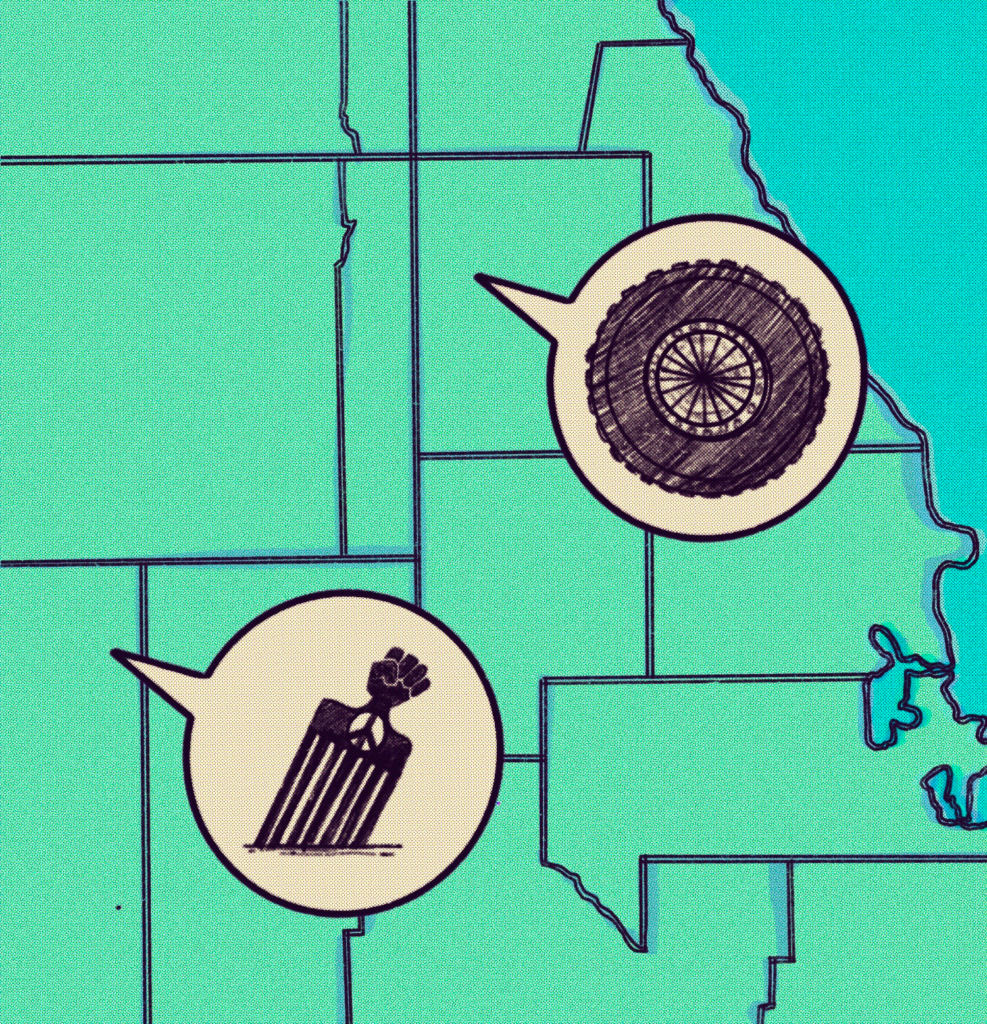

The Monumental Tour made its way to Chicago in June and brought to the South Side two sculptures: Hank Willis Thomas’s All Power to All People, a twenty-eight-foot tall hair pick, its handle raised in a Black Power salute, sits at Grow Greater Englewood’s Englewood Village Plaza. Arthur Jafa’s Big Wheel IV hangs in the front window of Blanc Gallery. Presented by Kindred Arts, the tour aims to bring large-scale sculptural work to communities that are affected by their messages the most.

“The placement of the sculpture also just challenges what a monument is,” said Andres Hernandez, of Wide Awakes Chicago, a network that practices activism through art and is co-producing the Chicago leg of the tour.

“Everyone’s first thought is we need the monuments alive and [to] memorialize this historic event or this historic person… and these are just like literally everyday objects that have symbolism. They have a weight, they have an interpretation. People can see themselves in these things, not just see someone else and their history and their achievement.”

It’s also important, Hernandez said, to place these monumental sculptures “off-the-traditional beaten paths.” “If they get to encounter it slightly differently, it’s important,” he added.

All Power to All People, made from aluminum and stainless steel, stands next to a formerly vacant lot that is now farmland providing sustainable food to the Englewood community. “We thought that it would be really important around some of the stuff that we’re doing in Englewood around land,” said Anton Seals, of Grow Greater Englewood.

With its title referencing the legendary Black Panther slogan, the sculpture is explicitly Black and represents a collective identity. “For us,All Power to All People at our site is a testament around what is taken from farmers,” Seals said. “You know, we work around Black and brown farmers across the city, and that notion of labor around power, who’s feeding you, nature, the environment—all of those things for us are embodied in a way, specifically around land…. Englewood has maybe neck and neck the most amount of vacant land in the city of Chicago.

“It’s an interesting thing that has happened in Black communities when they’ve been left behind or disinvested, and then what that rediscovery looks like, and then who gets to rediscover it,” Seals said.

While the meaning of All Power to All People is easier to grasp for most people, viewers of Big Wheel may need to take more time with the piece to interpret it.

“I love the monumentality of All Power to All People, and then it’s like, you’ve set the weight in this sort of gravitas of Arthur Jafa’s piece, which requires you to kind of slow down a little bit and kind of come up to it and take a longer look,” Hernandez said.

The monster-truck wheel that is Big Wheel, a seven-foot-tall tire wrapped in iron chains and a few bandanas, tells a story of Black wealth and migration. “It’s about the Black middle class and working in these factories and working in these industries and being able to create foundational wealth for your family,” Rhodes explained. Movement and migration are a part of Bronzeville’s history; the neighborhood experienced upper- and middle-class Black families migrating to other neighborhoods after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled restrictive covenants, a legal contract that prohibited homeowners from selling or renting their homes to Black people, unconstitutional in 1948.

These two sculptures—along with Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War—have been installed in other cities, including Philadelphia, Atlanta, and Washington DC, over the past two years, often at sites bearing similar history.

Why situate these sculptures in Englewood and Bronzeville rather than the Loop? Getting people to question the placement of public art like the sculptures in the tour is part of the impact the tour hopes to have on the communities they are found in.

“The mission has always been to consider supporting communities that are just as deserving [of] arts that speak to their rich history,” said Marsha Reid, the director of Kindred Arts.

“I have to justify why there’s one of a handful of art galleries in the Bronzeville neighborhood or in the whole hub of the South Side. These are like justifications…why are you doing what you’re doing? The real impact is to normalize these situations,”Hernandez said. “Public art can happen anywhere, right? People deserve half-a-million-dollar artworks in their neighborhood. And it’s not a big deal.”

The Monumental Tour is an act of cultural equity. The accessibility of the art is at the center of the tour’s goals. Once access to public art is available, conversations can happen. “What we try and do is make things available and accessible and use our muscle and might and relationships to make something available to as many people as possible. Because then you do have the moment where somebody is completely there, they have that ‘aha’ moment where then art becomes something meaningful to them,” Rhodes said.

Seals, who grew up in South Shore, sees All Power to All People through a nostalgic lens. “I thought about my grandmother and I thought about 74th and Champlain. I thought about the SoftSheen, the blue grease, and having to get your hair braided, unbraided, which was a very uncomfortable thing for me when I had hair as a kid. And getting your hair picked was never what you wanted to do. So when I see the Afro pick, the immediate thing I’m always thinking of is that smell of Sulfur 8 and Softheen grease and the blue grease,” said Seals. “I think of the progress that we’ve made [at Grow Greater Englewood] too.”

“When I see both works, it just really reminds me of the complexity of Black experiences,” said Hernandez.

“Our experiences are much more complex than even sometimes what one symbol may represent.”

Kendall Hope, from Roseland, shared his thoughts after viewing All Power to All People: “It’s nice to see art like this in Englewood instead of the more gentrified areas in Chicago. A great piece by a Black artist in a Black neighborhood for the people of the neighborhood to see…I think that’s beautiful.”

The Monumental Tour sculptures are on view at 5801 S. Halsted St. and 4445 S. Martin Luther King Dr. through August 30. For more on the tour visit bit.ly/36QZi0I.

Isabel Nieves is a Puerto Rican and Mexican American journalist and multimedia producer based in Pilsen, and the Weekly’s arts editor.