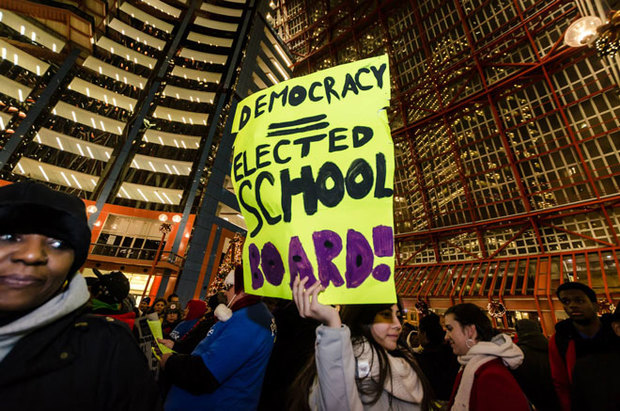

As advocates and organizers celebrate Chicago’s first ever elected school board signed into law last month some are turning their attention to the next task: fighting for noncitizens to be able to vote for school board candidates as well.

Democratic representation on Chicago’s Board of Education is something that organizers and advocates in the city have been fighting for for decades—currently, the board consists of seven members appointed by the mayor. According to the bill signed into law by Gov. J. B. Pritzker on July 29, Chicago will be transitioning to a fully elected, eleven-member school board by 2027, with the first elections in 2024 being held for a hybrid board—eleven appointed members and ten elected members—that will be installed in 2025.

But the ability to vote and run in school board elections will be limited to U.S. citizens.

Illinois State Senator Celina Villanueva (D-Chicago) introduced SB1565 in the Senate in February. This bill would allow non-citizens to vote in the school board elections across Illinois. “The conversation was always that this is a trailer bill,” she said. “That this is gonna go right after, and that we’re gonna move this, and put our energy in this, once we pass the elected school board.”

Before being elected to the General Assembly in 2018, Senator Villanueva, who was appointed to the State Senate in 2020 to fill the vacancy left by Martin Sandoval’s resignation, worked as an immigrant rights organizer at the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR). “I very much carry the experiences of the people in my community into the legislation,” she said, explaining that she represents the most Latinx state senate district in Illinois. “I have a huge population of non-citizens in my district.”

According to the Chicago Teachers Union, immigrant students make up more than forty percent of Chicago Public Schools’ (CPS) student population. And according to CPS data, as of October 2020, 46.7 percent of students in the district were Hispanic. “My parents, at one point, would’ve been covered in the scope of this bill, and they had CPS kids,” Villanueva said.

Although she introduced the bill, Senator Villanueva stopped short of claiming credit for it. “The idea of this bill was not mine,” she said. “This is something that had been percolating for a while with the different members of a coalition of community-based organizations that had been working on and really thinking about what an elected school board would look like in the city of Chicago.” These organizations include the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, and the Logan Square Neighborhood Association (LSNA).

Among these organizers is Monica Espinoza, a coordinator organizer at LSNA, a parent of two CPS graduates and two students at McAuliffe Elementary School, and a member of the McAuliffe Local School Council (LSC). For the past ten years, she has been organizing for an elected school board.

Espinoza is also undocumented, and now that the elected school board has been won, she is advocating for non-citizen parents like herself to be able to vote.

“At this point, I definitely refuse to let my people become a statistic just defined by migratory status, which is the result of many years of racist policies,” Espinoza said. “And I feel this is a perfect opportunity to change that, and to give our children a voice and become part of the school governance.”

Some advocates, though, are concerned about the risks of the bill as it is. Since noncitizens would still be unable to vote in other federal, state, and local elections, the bill would create a separate voter-registration affidavit specifically for them to vote in the school board elections.

“The downside of that is that these are people who would be known to be noncitizens,” said Fred Tsao, Senior Policy Counsel at ICIRR. “And once that information is disclosed on the part of the noncitizens, there really is no way to stop that information from being shared.”

In Illinois, statewide state political committees and government entities can buy statewide voter registration lists, and they are also available for public viewing in person at the State Board of Elections office.

According to Jianan Shi, the executive director of Illinois Raise Your Hand, two big concerns are protecting non-citizens during the voting process—specifically by making sure that groups like ICE are not able to use the information—and communicating to families the risks of registering to vote. “I was a noncitizen before, I understand how serious that is, and how much is at stake compared to one vote at a school election.”

Illinois is not the first state to consider noncitizen voting in school board elections, and advocates like Shi have been looking at its implementation in other places to inform their approach here. In November 2016, San Francisco approved a measure allowing noncitizens to vote in their school board elections. But its approval alone was not enough to guarantee successful implementation.

“San Francisco educated 60,000 immigrant families about this,” Shi said. “They formed a collective and they’ve done a lot of education to inform families what are their rights, how they can vote, how they can be protected, and how they can get actually involved in that part of their children’s schooling.”

Even still, the city saw low registration rates among noncitizens, likely due to the warnings they received. “San Francisco has a pretty damning affidavit that they put right at the top [of the voter registration form], and it’s like this could be used against you, please consult a lawyer, and so that’s pretty scary to put up there,” said Shi.

San Francisco’s voter registration form for noncitizens explicitly warns that any information provided to the Department of Elections may be obtained by ICE and other agencies, organizations, and individuals. “Those sort of warnings that they included for all the right reasons had the effect of deterring people from registering and voting more than they would have,” said Ron Hayduk, a professor of political science at San Francisco State University whose work focuses on political participation and immigration.

San Francisco spent more than $300,000 on new registration and outreach conducted by advocacy groups and community organizations to implement the bill. Right now, the Illinois Senate bill does not set aside money for outreach or education.

In contrast to statewide elections, noncitizens are allowed to run and vote for LSCs—elected boards at each public school in Chicago whose duties include approving the school budget, selecting principals, and approving the academic plan—because their elections are conducted within CPS. “I’ve been part of the LSC on and off for a good eight years, I would say, without fear of being wronged,” Espinoza said.

“The schools have protections, there’s confidentiality there,” Hayduk said. “They are able to be confident that their immigration status is not known, or if it is found out by a school board official or school official, that that information is confidential and is prohibited from being made known to entities outside the school system.”

Advocates have other concerns as well. Right now, the bill introduced by Senator Villanueva would only allow non-citizen parents, guardians, or caretakers of children in the district to vote in the school board elections. “As someone who does not have kids but is still concerned about educational issues, I would hope that the right to register and the right to vote would be extended beyond [them],” Tsao said. He added that it would be important to ensure that information about school board elections and voter registration would be available in multiple languages beyond English.

Despite these concerns, advocates and organizers across Illinois are going to continue to push for enfrenchisement of noncitizens in school board elections. SB1565 is still in the Senate, and there was a subject-matter hearing for it last month where advocates such as Tsao and Espinoza spoke. “I think that there’s a lot of folks that support the idea of it, but are also very interested in the process and how we get it done correctly,” Villanueva said. “So there’s still ongoing conversations around it.”

“We see this as just the beginning of building the right protections, having the right conversations to make sure this is inclusive, because there aren’t many areas that have done it,” Shi said.

And noncitizen parents say they will continue to fight for the ability to vote and influence their children’s education. “I don’t understand why our future generations of children have to pay and suffer for the hate of today,” Espinoza said. “If we come together and we really put our heads and our hearts, and we are honest with ourselves, we definitely need a board that represents a community that is underserved and is under-resourced.”

“I feel my kids deserve quality education, and I’m gonna advocate ‘til the end because I want to make sure that the sacrifice of me walking on that scorching heat in the desert leaving tears, sweat, and blood, literally, I hope that’s worth it.”

Madeleine Parrish is the Weekly’s education editor. She last wrote about CPS High Schools voting to keep or remove police.