This story was originally published by the Invisible Institute on October 27, 2022. To view footnotes, supporting documents, and for more information about the Police Torture Archive, visit chicagopolicetorturearchive.com/tony-robinson

Content warning: this story includes descriptions of police torture and gun violence.

Over three years, the Invisible Institute investigated the conviction of Tony Robinson, who has been incarcerated for more than a quarter of a century—and is serving a 100-year sentence—for the 1994 fatal shooting of nine-year-old Joseph Orr.

We found significant new evidence supporting Robinson’s innocence, including:

- a new alibi witness

- recantations from states’ witnesses

- information about three alternative suspects

- allegations that law enforcement pressured witnesses to implicate Robinson

The Invisible Institute also conducted a pattern and practice analysis of the torture allegations in Robinson’s case against detectives in Robinson’s case—officers associated with former police Commander Jon Burge.

Case Summary

On August 9, 1994, nine-year-old Joseph Orr was playing with other children and young adults outside their makeshift clubhouse in the Washington Park Homes public housing development in Chicago. At 3:50pm, a gunman approached the group, began shooting and then ran off. Orr was shot in the back and died. The homicide was reportedly part of an ongoing feud between two street gangs, and at the time, Orr was the thirty-seventh child under the age of fourteen to be killed in Chicago.

Police from the Chicago Housing Authority and from the Chicago Police Department arrived at the scene. Witnesses said they saw the shooter exit from a burgundy car with three people in it. Multiple witnesses described the shooter as a Black male in his early twenties, with a light complexion and a short ponytail, wearing dark clothing.

Within an hour of the shooting, officers picked up two teenage boys (later co-defendants with Robinson)—one of whom, according to police, was being chased by a group of people and another who was found driving a maroon car that witnesses identified as the shooter’s. Several hours later, police brought in twenty-two-year-old Tony Robinson and shortly after that, another teenage boy (a third co-defendant).

Police interrogated the young men. According to Robinson, they beat and tortured him into a coerced confession.

There was no physical evidence implicating Robinson, whereas two of his co-defendants had a palm print and thumbprint on the car, respectively, and the third co-defendant had gunshot residue on his hand.

There were also discrepancies in the statements of witnesses implicating Robinson. Photographs introduced at trial demonstrated that one woman who claimed to have seen Robinson running with the gun after the shooting couldn’t have witnessed it because of leaves obstructing her view. Two juvenile witnesses, one of whom later had criminal charges against her dismissed, identified Robinson months after the shooting. Another witness, who initially told police the shooter was a man named “Kirby,” later changed his identification to Robinson. In exchange for this witness’s testimony, the state agreed not to use his gang affiliation against him in his pending attempted murder cases and to relocate his mother.

At trial, three witnesses testified on behalf of Robinson’s innocence. Two were girls who had been playing with Orr when the shooting occurred, one of whom saw the shooter and identified him as a man named “Tick.” Their mother testified that she had tried to tell this to police, but they never took her statement.

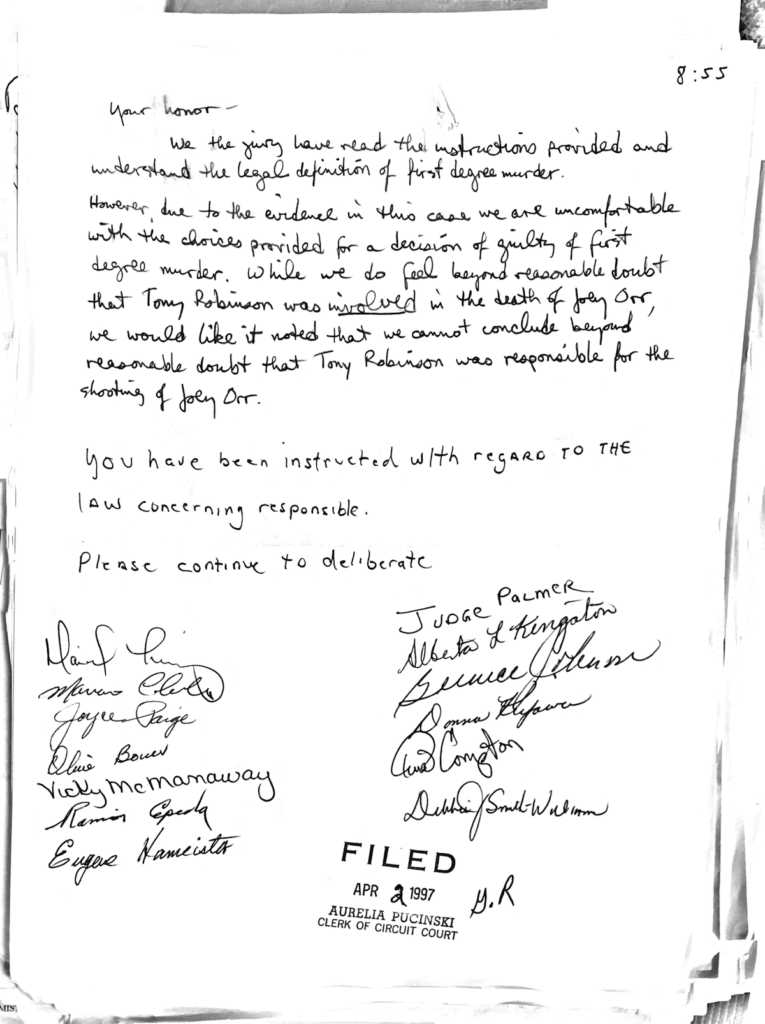

Robinson’s jury did not feel comfortable finding him guilty of first-degree murder at first. During deliberations, the jury sent out a note in which they stated that though they felt he had been involved, they could not “conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that Tony Robinson was responsible for the shooting of Joey Orr.” Despite this concern, the judge directed the jury to continue to deliberate. In the end, they found Robinson guilty of first-degree murder.

All of Robinson’s co-defendants, two of whom took plea deals, were convicted and have since been released from prison. Robinson remains the only one still incarcerated.

The Invisible Institute spoke with a member of the Orr family, who declined to comment on the case.

Robinson’s History

From an early age, Robinson was placed in special education schools and medicated for hyperactivity. He never made it to high school. Multiple family members told the Invisible Institute that he couldn’t read or write very well. Robinson’s mother, Alberta Jones-Boyd, stated, “Tony didn’t go too far in school. He couldn’t read, couldn’t write, couldn’t understand too much.”

Although Robinson had a record of arrests (for robbery, theft and possession of a controlled substance) and had served time in a state penitentiary before the Orr case, he had no criminal record involving weapons or firearms. Robinson told the Invisible Institute that his family were “boosters” and that he wanted to have nice clothes and things.

Robinson was both hit in the head with a pipe and stabbed in the head when he was thirteen-years-old, according to his mother’s trial testimony. Jones-Boyd stated that her son’s intellectual disability was exacerbated after those beatings. Robinson testified in a pretrial hearing that following the traumatic brain injuries, he experienced visual and auditory hallucinations.

Robinson asserted that when police brought him into the station to interrogate him for Orr’s murder, they did not allow him to take his medications despite his requesting them. During a hearing on the motion to suppress his statement to police, Robinson testified that without his medications, he started hearing voices and seeing demons and bulls charging at him while in the interrogation room.

Robinson’s jury trial did not start until March of 1997, almost three years after Orr’s killing. From 1994 to 1997, Robinson was found unfit for trial three times by two different psychiatrists. One wrote that Robinson “is in marginal contact with reality.”

While awaiting trial, in June 1995, Robinson was sent to Chester Mental Health Center. In November of that year, another psychiatrist, Dr. Philip Pan, evaluated Robinson. Pan, a postdoctoral fellow in psychiatry in law, was not board-certified.

After a session lasting “approximately forty-five to sixty minutes,” Dr. Pan deemed that Robinson was fit to stand trial with medication.

Pan declined to comment about his evaluation, citing Cook County Forensic Clinical Services policy.

Robinson told the Invisible Institute that he was hallucinating during his trial: “It seemed like someone was behind me or someone was right next to me. … I really couldn’t understand what was going on.”

Robinson’s Torture Allegations

In addition to asserting his innocence, Robinson has consistently maintained since his arrest and interrogation on August 9, 1994, that Chicago Police detectives beat and tortured him into confessing.

The detectives—Albert Graf and William Foley—worked at Area 1 Police Station and are known associates of former police Cmdr. Burge. Graf and Foley are accused of participating in many instances of torture. Between the two of them, they are defendants in at least twenty-three lawsuits alleging torture, and they are often named alongside other notorious Burge associates, such as John Halloran, James O’Brien and Kenneth Boudreau. Foley also appears in at least six claims filed with the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission, and Graf appears in at least three claims. Both Graf and Foley left the force in 2003 and 2004, respectively. A third detective, Michael Clancy, was present for parts of Robinson’s detention.

(Calls for comment to the detectives were not returned, and in one instance, Graf hung up on an Invisible Institute reporter; Foley is deceased.)

Robinson described to the Invisible Institute several acts of torture, including police repeatedly choking him until he blacked out, and police placing a towel over his hands and beating them with a flashlight. He also reported that police repeatedly spit on him.

“I wanted to call my momma so bad,” Robinson told the Invisible Institute. “Police almost immediately got violent.”

In an interview at Hill Correctional Center in May 2022, Robinson said he was taken to a windowless, gray room with a table in the middle, handcuffed to a wall, and brought to the table for the torture. He said once Graf entered the room, “they started getting aggressive.”

Robinson said that a fourth officer “choked [him] out” and “pulled down my pants and threatened to put a broom in my rectum”—a detail that Robinson went years without disclosing to anyone. “It’s embarrassing to me,” he told the Invisible Institute at Hill Correctional Center.

Robinson said that to avoid any more injuries, he falsely confessed to being a lookout in Orr’s murder.

Robinson remembered that his public defender took pictures of the marks on his hand that were later shown in court.

Pattern and Practice

Detective Albert Graf

At the time of Tony Robinson’s arrest, Albert Graf was a detective at Area Central Unit 610. He was one of the officers who helped conduct Robinson’s lineup and was considered an “investigating detective” on the case. He went on to testify at Robinson’s trial in 1997, claiming that Robinson was not injured when he was taken into lockup and that when he saw Robinson on August 9-11, he did not see Robinson’s hands swollen. Graf also testified that he had a short conversation with Robinson, lasting about seven to ten minutes. Finally, Graf testified that he helped with all the lineups in the investigation.

Over the more than thirty years of his career, Graf has been named as a defendant in numerous lawsuits alleging police abuse. His co-defendants include several prominent Burge associates; among them, John Halloran, James O’Brien, and Kenneth Boudreau.

In a 2007 lawsuit, Robert Wilson asserted that during a thirty-hour interrogation in 1997, several police officers (including Graf) verbally threatened him, physically attacked him and coerced him into signing a false confession for attempted murder. Wilson said he was also denied sleep, food, and his blood pressure medication. This detail is notable because Robinson also claimed that he was denied medication during his interrogation. (Robinson took several medications due to his previous head injury.)

Wilson signed a confession written by another police officer. Wilson also claimed that the officers involved “manipulated” the victim into positively identifying Wilson as her attacker, even though she initially denied it. In 2006, Wilson’s conviction was reversed, and he sued the city of Chicago, receiving a $3.6 million settlement.

Graf is accused of torture in another case, the 1994 arrest and conviction of Nevest Coleman for the rape and murder of Antwinica Bridgeman. According to Coleman’s 2018 lawsuit, he was interrogated by about eight officers (including Graf) without having his Miranda rights read to him. When Coleman refused to confess, the officers “employed a range of physically and mentally coercive tactics,” with one of the officers (unnamed) calling him a “lying-assed n—-r” and punching him in the face multiple times. The lawsuit also asserts that the officers fed Coleman false information about the rape and murder, which Coleman repeated in a false confession that landed him in prison for nearly half his life. He was released in 2017.

The same officers then used Coleman’s false confession to elicit another false confession for Bridgeman’s rape and murder from Derrell (Darryl) Fulton, as alleged in a separate 2017 lawsuit. Fulton reported that he was also physically and verbally abused during his interrogation by officers who threatened to “put a bullet in his brain.” Fulton spent the next twenty-three years incarcerated for a crime he did not commit, before being released in 2017.

Detective William Foley

At the time of Tony Robinson’s arrest, William Foley was a detective at the Violent Crimes Dda 1 Unit 612. He was also considered an “investigating detective” on Robinson’s case and helped conduct Robinson’s lineup. He later testified at Robinson’s trial, claiming he was not present for Robinson’s interrogations (Graf conducted the interrogation), but that he was present for his court-reported statement. Foley also said he interrogated one of Robinson’s co-defendants with his partner, Detective Michael Clancy.

Foley is a defendant in several lawsuits involving police torture. These lawsuits include those of Nevest Coleman and Derrell (Darryl) Fulton—Foley was an arresting officer in Fulton’s case and was present during Coleman’s torture.

Foley was the lead detective in several other cases that have since been overturned, leading to lawsuits in which the city of Chicago was ordered to pay settlements to torture survivors. In one case, a group of teenagers known as the “Englewood Four” (Michael Saunders, Harold Richardson, Terrill Swift and Vincent Thames) were reportedly physically assaulted and threatened by police officers (including Foley) into false confessions for a 1994 rape and murder. All the boys were teenagers and weren’t interrogated in the presence of a parent or lawyer.

In Saunders’ lawsuit, Foley is named as one of the officers who “used coercion and threats—both physical and verbal—to force Saunders to implicate himself.” This included slapping, pulling out his earring, and telling him if he didn’t confess they would take him out to the train tracks and shoot him. The lawsuit said Foley and several other officers also “falsely represented in their written reports and conversations with trial prosecutors the circumstances under which Saunders’ ‘confession’ was obtained.”

Richardson also named Foley in his lawsuit, describing how officers threatened to take him to “a nearby viaduct and kill him.”

Another man, Javan Deloney, alleged in a case before the Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission (TIRC) that in 1991 Foley slapped and punched him.

Several other TIRC cases involving Foley contain allegations consistent with Robinson’s: Antoine Ward reports that Foley, Clancy and other officers stepped on his left hand during his 1994 interrogation; John Plummer claims police (including Foley and Clancy) hit him in the face, stomach and side with a flashlight during his 1992 interrogation; and Arnold Day and Reginald Henderson report that Foley and other officers choked them during their police interrogations in 1992 and 1994, respectively.

Detective Michael Clancy

At the time of Tony Robinson’s arrest, Michael Clancy was a detective at Area Central Unit 610. He, too, was considered an “investigating detective” on Robinson’s case and helped conduct Robinson’s lineup. Clancy has been named in several lawsuits alongside other Burge associates, including Boudreau, Halloran and O’Brien, as well as Foley and Graf.

One such case was that of Tyrone Hood, who was convicted of killing his brother Marshall Morgan Jr. in 1993. In a 2016 lawsuit, Hood claimed he was held in police custody for several days on two separate occasions, during which time he was “repeatedly interrogated, coerced, and beaten” by several officers associated with Burge (including Clancy). Hood said these officers beat his co-defendant Wayne Washington, coercing a false confession. In a lawsuit, Hood said these officers “engaged in a tapestry of egregious wrongdoing, including fabricating evidence, threatening witnesses and withholding exculpatory evidence.” Hood has since been released from prison.

Clancy was also involved in the case of Sean Tyler, who claimed that, during his 1994 interrogation for murder, he was beaten in the chest and face so badly that he vomited blood. Tyler named Clancy as an officer who punched him in the face. Detectives Foley and Graf were also listed as officers involved in Tyler’s case.

Together with Graf, Foley and other Burge associates, Clancy is named in the lawsuits of Derrell (Darryl) Fulton and Nevest Coleman.

New Evidence

The Invisible Institute’s investigation into Robinson’s case found:

A new alibi witness who supports Robinson’s innocence, Tiffany Esper

Esper told reporters from the Invisible Institute that she knew Robinson had not been involved in Orr’s shooting because he was in her ninth-floor apartment unit—in a building about two blocks away from the crime scene—at the time of the incident. (Robinson had been renting a room in Esper’s apartment and lived there with Esper and her children for several weeks before the shooting occurred.) “He was up at my house,” Esper said. “[He] didn’t do that.” Esper said she had just left her apartment to take the elevator down to see her husband when the shooting started outside: “How you be on the ninth floor and there’s a shooting down there?” On the day of the shooting, Esper also witnessed police take Robinson into custody. “All I know is police grabbed him,” she said. “They put it on him.” Esper, who was pregnant at the time of the incident, said the police also grabbed her, and she swung at them. Esper said police threatened to take her kids away. “Whatever they pulled that daggone day,” Esper said, “they lied.” Esper also said she later heard that a young man other than Robinson had been responsible for the shooting. This alternative suspect has since died.

A recantation from a key state’s witness, Melvin Irons

In an interview with the Invisible Institute, Irons has recanted his prior testimony, alleging he was pressured to testify against Robinson in exchange for a deal on his own pending charges. Irons previously testified that on the day of Orr’s shooting, he had heard Robinson talk about wanting to retaliate after being shot at the night before. Irons now says he never heard any conversation involving Robinson and did not know him before this case. “I’d been feeling really guilty,” Irons said in a 2021 interview with the Invisible Institute. “Sending someone to jail for ninety-nine years,” he continued, “that was wrong of me to do that.” Irons identified Brian Sexton, one of the prosecutors assigned to Robinson’s case, as the attorney who fed him the false retaliation story. Sexton faced criticism in 2016 after reportedly testifying falsely in a federal civil rights trial regarding the prior testimony of a gang expert, according to a 2018 investigation by Injustice Watch. According to this investigation, Sexton made these false statements during the retrial of Nathson Fields, who endured two criminal trials and three civil trials for a 1984 double homicide. Retried in 2009, Fields was acquitted of the murders after two witnesses recanted their testimony. Fields later won a $22 million jury verdict for his wrongful conviction. In 2018, the Chicago Council of Lawyers found Sexton to be not qualified for a judicial seat, citing a number of convictions that were overturned due to his conduct. Sexton, who is now in private practice, has a history of representing Chicago Police officers accused of misconduct, including an officer who allegedly pressured a witness to the fatal shooting of Laquan McDonald to change her story.

Brian Sexton declined to comment on these allegations.

An eyewitness for the state, Derrick Stroud, who now says he never saw the shooter’s face

Contrary to Stroud’s 1997 testimony, in which he said he saw the gunman exit a car and start firing shots, Stroud said in a 2022 interview with the Invisible Institute: “I couldn’t see who was shooting. My back was turned.” Stroud explained that he had been right behind Orr when he was shot. “I can’t forget the shooting,” he said. Despite not having seen the shooter’s face, Stroud identified Robinson as the gunman in a police lineup the morning after the shooting. He also identified the gun Robinson had allegedly used in the shooting by viewing a photo of weapons that police had recovered from an apartment in Robinson’s building. At the time of Robinson’s trial, Stroud was in custody on two pending attempted murder charges. Stroud initially testified that he had made no deals with the state in exchange for his testimony. However, he later acknowledged at trial that the state had agreed not to use his testimony regarding gang membership against him in his two pending cases, and the state had also agreed to relocate his mother for her protection.

An eyewitness for the state, Konaa Bennett, who now says she did not know who the shooter was but felt pressured to identify Robinson

Bennett told the Invisible Institute that she saw a lot of people in the area running at the time of the shooting, and she did not know who shot at the kids. “I don’t know who the shooter was. I never said who shot,” Bennett said. According to Bennett, when police approached her to participate in the case, she told them multiple times that she didn’t know who the shooter was. “I didn’t know. I was telling them. They forced me,” Bennett said. “They made me do this. I was a kid at this point.” Bennett, who was 13 at the time, did not view a lineup until almost three months after the shooting, at which point she identified Robinson as the shooter, as well as another individual as the driver of the getaway car.

An eyewitness for the state, Janieka Johnson, who thought “Kirby” was convicted of Orr’s murder, not Robinson

Johnson, who can no longer remember the shooter’s face except that he was “brown-skinned,” said in a 2022 interview with the Invisible Institute that she saw “a person running through the field with a gun and everyone saying get down, so I got down. … I fell to the ground, I heard the shots, I looked up, and Lil Joe was laying there.” When asked if she saw the shooter’s face during those several seconds before Orr was killed, Johnson replied, “I thought I did.” Johnson, who was fourteen at the time, viewed a police lineup two months after the shooting and identified Robinson, according to records, but “I thought it was Kirby” who “got all that time,” Johnson said.

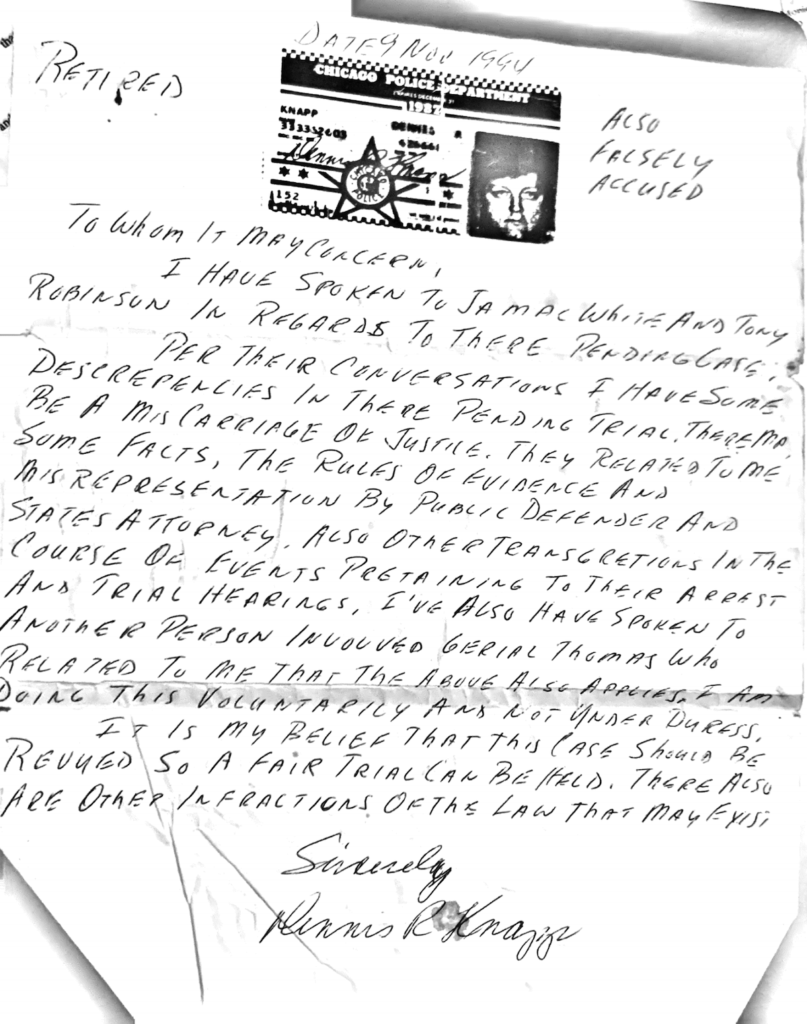

A letter from a retired (now deceased) Chicago police officer, Dennis Knapp

Three months after Orr’s death, Knapp wrote a letter to Robinson’s family saying that a miscarriage of justice may have occurred in Robinson’s case. Knapp met Robinson and one of his co-defendants while Knapp was also in custody. According to his letter, Knapp said he learned from them about issues related to their arrest and court proceedings and believed the “case should be reviewed so a fair trial could be held.”

The Invisible Institute is a nonprofit journalism production company on the South Side of Chicago that works to enhance the capacity of citizens to hold public institutions accountable.