Earlier this year, dozens of organizations, government officials, and neighbors mobilized to help meet the short-term needs of the 3,700 migrants that Texas Governor Greg Abbott bused to Chicago as part of a political stunt. As the migrants, many of whom are seeking asylum in the United States, settle down to find housing and work, enroll in schools, and seek medical care, they will also need to put together their applications for asylum in order to stay in the country in the long-term.

Asylum seekers are people who have left their home country to seek protection from prosecution. To be granted asylum in the United States, the Refugee Act of 1980 requires that a person must demonstrate past persecution or “credible fear” of persecution in their home country. Evidence of trauma and attack in their home country, documented in the form of a forensic medical or psychological affidavit, help to strengthen their asylum case.

According to a national analysis of asylum seekers from 2008 to 2018, those with forensic medical evaluations were twice as likely to obtain immigration relief—a 81.6% grant rate of those with medical evaluations as opposed to the national asylum grant rate of 42.4%.

“When you do have a forensic evaluation, it tends to only benefit [a case], especially if it is well done,” said Aimee Hilado, assistant professor of social work at the University of Chicago and chair of the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant Mental Health.

There is clearly a need for forensic evaluations in Chicago: of the 2,696 asylum applications filed in the last quarter of 2021 in Chicago, for example, only 1,165 or forty-three percent were completed, according to USCIS data from fiscal year 2022. Of the 1,165 cases that were heard, only 330 or twenty-eight percent were granted asylum.

According to Immigration Court Backlog Tool by Syracuse University, Chicago currently has 87,489 pending asylum cases, with an average wait time of over 800 days. “The backlog of applications that are waiting, I think that they have placed greater pressure on making these cases incredibly strong,” Hilado said. “And that’s where forensic evaluations come in.”

The Midwest Human Rights Consortium (MHRC), part of Refugee Immigrant Child Health Initiative, is one attempt to address the need for more forensic evaluations and trained evaluators. The group consists of mental health providers, physicians and other health professionals who provide evaluations for the National Immigration Justice Center.

MHRC launched in 2019 by organizing the first forensic asylum evaluation training conference in Chicago. A total of 103 attendees went through the eight-hour full-day training. Since then, the group has organized quarterly mentorship meetings about clinical cases and invited guest speakers.

MHRC operates as a referral network which connects immigration attorneys with trained evaluators. In the past three years, MHRC has received and processed over 160 requests for evaluations, mainly of asylum seekers from Honduras, Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador, and has been able to fulfill two thirds of received requests.

MHRC partners with several institutions including Loyola Medicine, the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital, the UIC College of Medicine, and the DePaul School of Social Work.

Alongside MHRC, organizations including the national non-profit Physicians for Human Rights and the nine regional organizations of Society of Asylum Medicine also offer evaluations to asylum seekers.

Minal Giri, co-founder of MHRC, said the length of evaluation takes six to eight hours, including conversation with the immigration lawyer, picture documentation, and writing the affidavit.

Abubakr Meah, an immigration attorney who takes in asylum cases, said many of his clients have experienced physical violence and traumatic flashbacks from their home country.

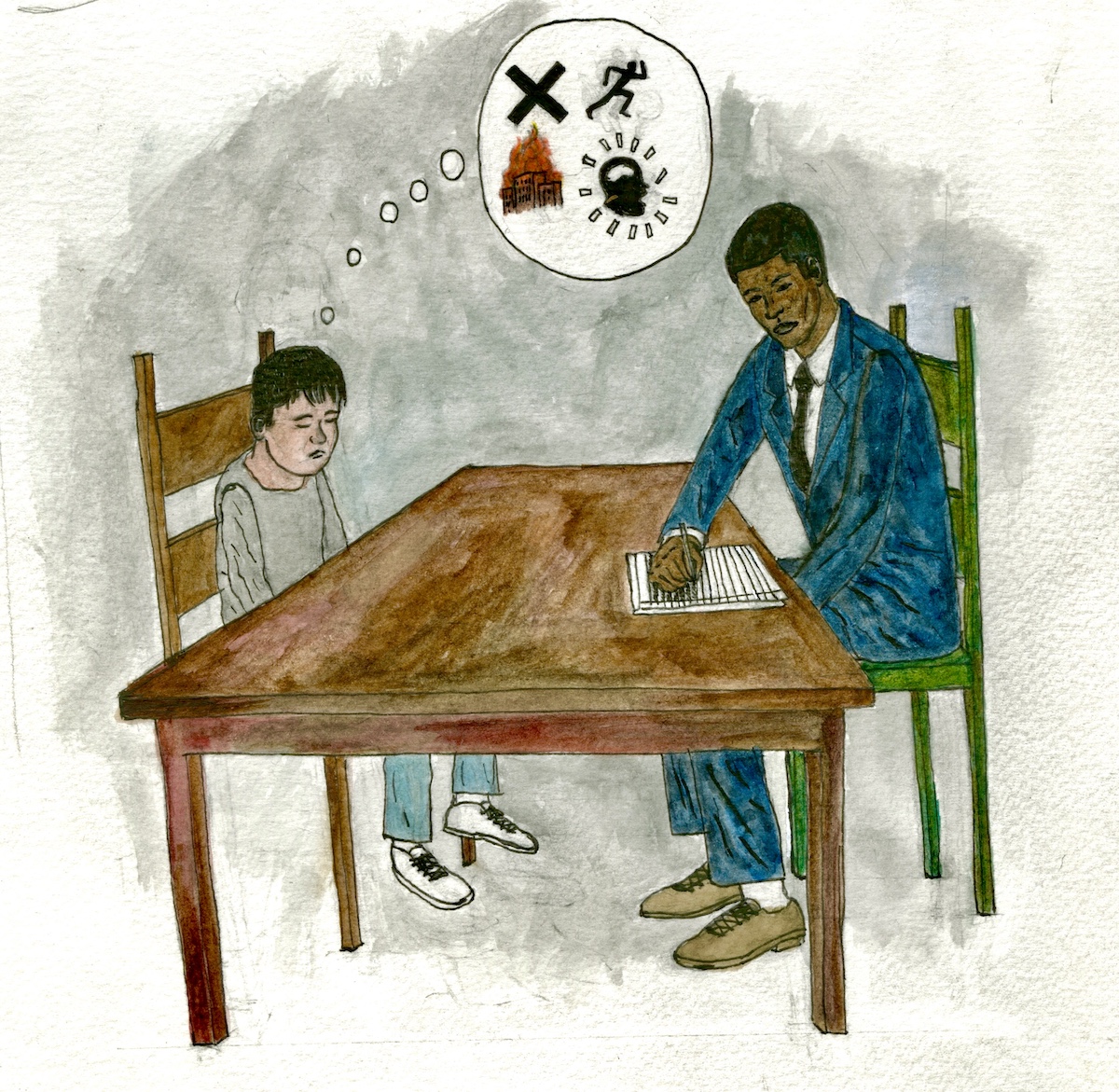

The evaluation includes two parts. First, the history of the applicant, starting from their childhood, the persecution that led to departure from the home country, to trauma during their journey and border-crossing. Second, the physical or objective findings, similar to an injury or abuse exam.

During the forensic evaluation, the health professional documents medical issues such as scars from maltreatment, Giri said. The psychological evaluation further supports the asylum cases by documenting trauma from the asylee’s experiences, such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, or depression.

All the findings are documented in a private note before being transcribed and printed as a medical affidavit, said Yessenia Castro-Caballero, one of the doctors who founded the Loyola Medicine Asylum Clinic at MacNeal Hospital

Hilado said she usually schedules two hours for the first evaluation and utilizes standardized instruments to measure symptoms of psychological trauma.

Hilado said she attends to the vulnerability of her clients and spreads out the sessions if their experience is difficult to process. “I think sensitivity in doing the evaluation does lead to the most accurate depiction of a person’s experience,” Hilado said. “And that’s why it takes time.”

Hilado teaches four classes a year as an assistant professor. The forensic evaluation will sometimes require her to provide oral testimony before court. She said funding wouldenable evaluators to sustain this service.

“That’s where I feel like money support can be useful,” Hilado said. “Not necessarily as an added income stream but ways to work within the systems already [in place] with people that are eligible to do this work.”

The practitioners typically receive support and clinical space through their institutions or, if those are not accessible, completely pro bono. Hilado found support through RefugeeOne, a non-profit organization where she worked for eleven years that established a forensic room for the evaluations.

Castro-Caballero said it takes time to complete the training and establish the programs at an institutional level without federal funding. “We’re able to provide standardized, forensic medical evaluations and try to cover a huge gap in this type of work,” Castro-Caballero pointed out.

Strong federal support would subsidize the infrastructure for training, clinic setups, and a workforce that would give more asylum seekers a chance to stay.

Correction 1/25/23: Details around requests received by MHRC were updated.

Chelsea Zhao is a master’s student of Health, Science and Environment Journalism at Northwestern. Her previous works appeared in Cicero Independiente and Chicago Health. She is passionate about covering topics of social justice, health and environment.