Had Michael Brown survived the summer, Monday, November 24, would have been a calm, snowy night. It wasn’t. It was a night on which the people of Chicago gathered in solidarity with the people of Ferguson, and made clear that a fundamental problem demands radical justice. An indictment of one man would not have been sufficient.

At 6:30pm, a crowd began to gather outside the headquarters of the Chicago Police Department, at 35th and Michigan, where at least a dozen officers stood guard. The decision of the Michael Brown case was not expected until 8pm, but there was more than enough to talk about in the meantime.

“It’s important for us, in this country, to understand how many people have been targeted by the state on a regular basis,” Mariame Kaba, one of the organizers of the Chicago event, explained to the crowd.

Protestors were a mix of old and young. One older woman pushed past me to ensure her sign would be seen from the road. And, after a few scattered chants of “all lives matter,” We Charge Genocide delegate Malcolm London stepped up to assert that “black lives matter” was what needed to be heard today.

A few minutes later, Frank Chapman, a founder of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, spoke. “We started fighting police crimes forty-some odd years ago with our organization,” he said. “We got started right in the wake of the murder of Fred Hampton, who was a member of the Black Panther Party. Back then, they were systematically murdering and killing off the black leadership, particularly the young, revolutionary black leadership. And to some extent they succeeded, because Fred is dead. But he said you can kill the revolutionary, but you can’t kill the revolution. And so I’m glad to see everybody here today, because you witnessed today. The struggle’s starting all over again. What we did back then you’re going to do today, and you’re going to do it better.”

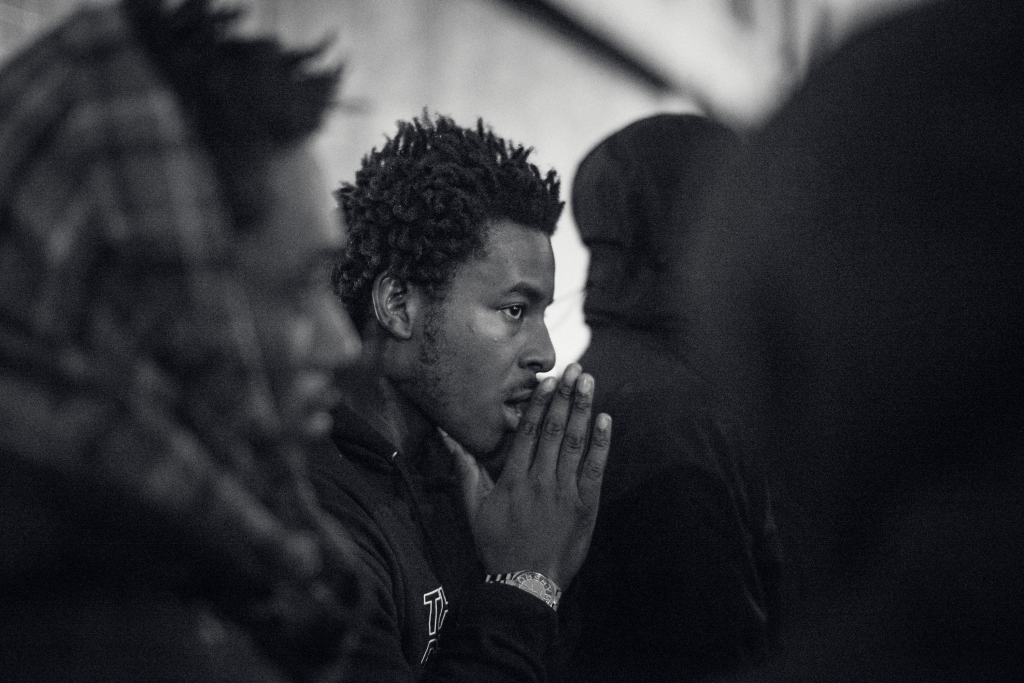

At 7:51pm, CBS tweeted that Darren Wilson had not been indicted, and we observed four and a half minutes of silence, in honor of the four and a half hours Michael Brown’s body had been left on the ground.

After a few minutes of chanting, it began snowing softly again, and we gathered around a bullhorn, where someone was live-streaming the official jury decision from Ferguson. The announcement, from chief prosecutor Robert McCulloch, was exasperatingly long, though phrases like “the law authorizes police officers to use deadly force in certain situations” made clear what everyone already knew.

At 8:34pm, I got the mass text from protestors in Ferguson, announcing the decision to over 17,000 people who’d signed up. “The fight continues, the movement lives,” it concluded.

We had already started marching east on 35th Street, as the younger leaders led chants of “no justice, no peace,” “hands up, don’t shoot,” and, most powerfully, “WE SHUT SHIT DOWN.” We turned north on King Drive, and then east on 31st Street. We turned left down the exit ramp onto Lake Shore Drive. We walked north and traffic stopped. People got out of their cars and shouted with us. We crossed to the northbound side of Lake Shore and started marching up that.

While this was happening, protestors in Ferguson were brutally teargassed. President Obama was telling the country, “No one needs good policing more than poor communities with high crime rates.”

But we went on past McCormick Place and Soldier Field, turned west on Balbo and soon threaded a way north. More people joined downtown, where the chants of “black lives matter” resounded. There had to be over a hundred police officers blocking the streets. We passed City Hall, stopped at the United Center, and took the streets again. We didn’t stop until we’d reached the river, and even then some people continued east.

It was never about Darren Wilson. “They killed Mike Brown,” protestors chanted. “They” still stand to be indicted.