“He points out into the overgrown green where his sister Bertha once gardened,” writes Pria Anand, in the journal she kept in Colombia. “I see bananas and trees and long grass, but only one flower, a tiny one, growing like a weed by the shed.”

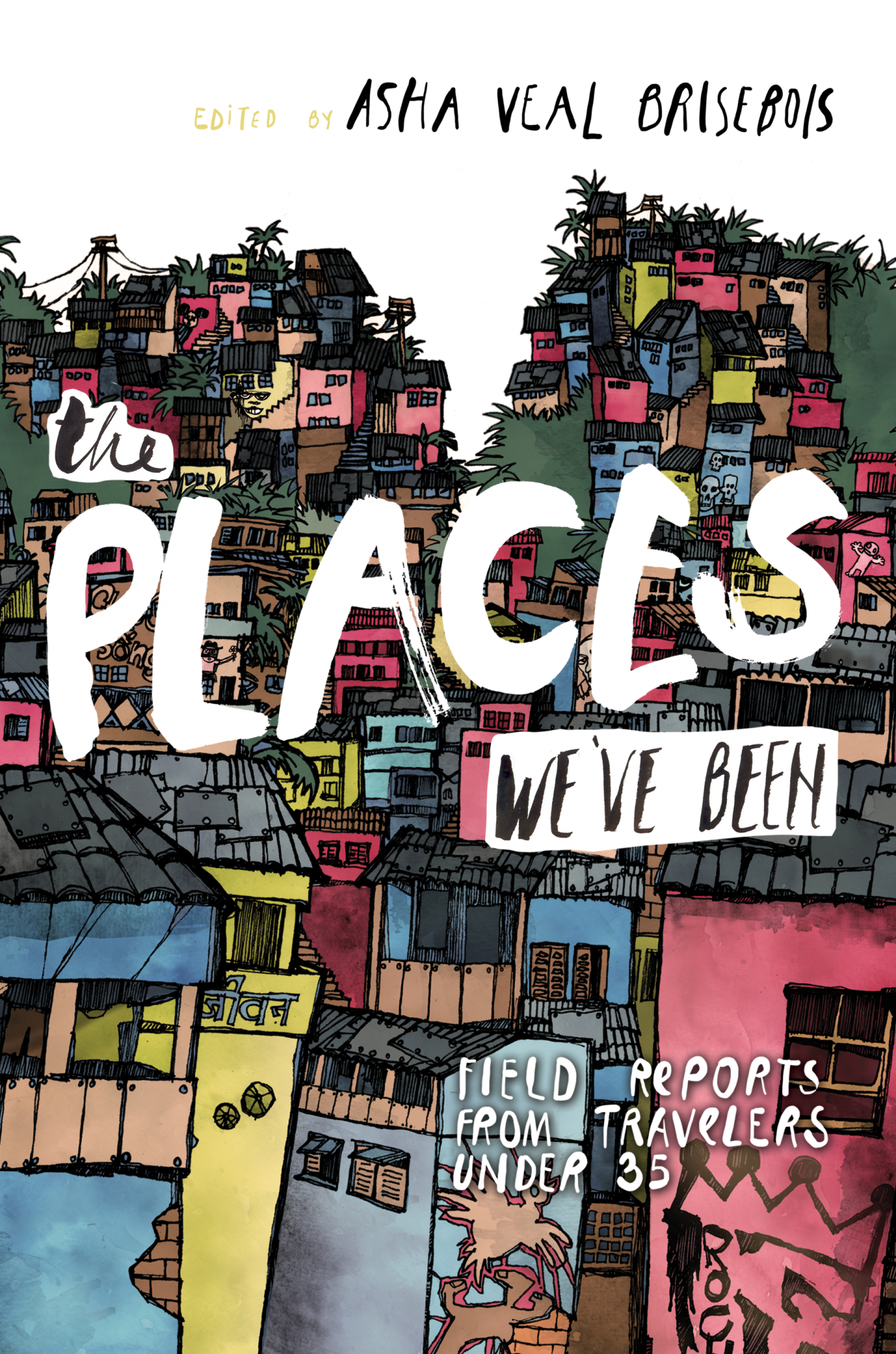

Reading The Places We’ve Been, which includes Anand’s work and that of forty-seven other travelers (forty-eight if you count editor Asha Veal Brisebois) feels a bit like walking into that back lot looking for a garden, and finding instead a whole mess of plants you weren’t expecting. Brisebois founded The Places We’ve Been books in Chicago in 2011; the collection is the publishing house’s first finished volume, reaching beyond the city to cull work from international contributors. The book is subtitled “Field Reports from Travelers Under Thirty-Five,” and many of the participants are activists, explorers, or artists. Some of them are one or more of those things before they are writers; at times their dispatches are rough around the edges.

This can make the four-hundred-page collection feel overgrown. But it’s not without its flowers. Many of the pieces feel welltended, written as much for the sake of writing as telling. And some of the less lit-focused contributions are as sturdy as trees: interviews with extraordinary people, straight reports from far-flung places, pieces that feel like letters home.

In her editor’s note, Brisebois borrows from Lee Gutkind, founder of the magazine Creative Nonfiction, to define the genre: “true stories, well told.” But within that sort of writing there is often another gauntlet thrown down, a deepening of the “well told” part that demands a “so what.” Writer and long-time Washington Post columnist Gene Weingarten, who has written some of the best travel stories I’ve ever read, writes that he tells his young reporters that their pieces are always, one way or another, about the meaning of life. Whether or not you buy that (he makes a good case), I know that I seek in reading nonfiction a telling that gets at a truth I care about, or writes a truth so well that I am at least startled by its true-ness.

In travel we face a similar demand. There exists the idea that travel is inherently virtuous, more than a just a luxury. It is a broadening, a chance to open your mind and see yourself in a different light. And this idea of reflection comes through in many of the anthology’s pieces, as young writers compare themselves to foreign counterparts.

In her account of a trek through China, Sierra Ross Gladfelter writes about the gulf between herself and her Tibetan hosts, yak herders sleeping on the other side of their dung-burning stove—they are nineteen and twenty to her twenty-two. In “Assault Rifles in the Ruins,” Frank Izaguirre waits out the rain with a cluster of Colombian teenage soldiers. Shadowing a midwife in Pachaj, Guatemala, Liz Quinn writes: “Surrounded by nursing mothers younger than I was, I felt my breasts to be conspicuously small, inert, and useless.”

Recounting a conversation in the midst of months of travel, Lisa Hsia says, “Traveling the world sounds like something a cool person would do, and I guess I just thought that once we started, I would become cool too. But now…I just feel like myself.” Maybe virtuous is the wrong word. But the traveler does embark hoping for transformation, and when they return, the inevitable question—“how was it?”—implies others. How are you better? How are you cooler? What have you learned? At times, the pieces in The Places We’ve Been thrust suddenly at answering those questions—and the “so what?”—in their final lines. Sometimes those conclusions are presented so neatly that they ring hollow, more a forced moral than an insight.

Of course, many of those included in the anthology are working writers, even as they are other things. Some identify themselves explicitly, writing about writing, others play with form to the same effect (here I’m thinking of poet Laura Madeline Wiseman’s “How to be a Russian Sleeper for the U.S.,” a set of flowing guidelines in the second person). Still others manage to convey their craft more quietly, their true stories strikingly well told.

As with most anthologies, The Places We’ve Been is best read any way other than cover to cover. It risks the fatigue of a long trip, when homesickness takes the traveler and newness starts to feel old. The book is organized by continent, but by reading start to finish one might miss Mike Madej’s three-page narration of a single night in Kenya, or Molly Headley-Benkaci’s pretty and brutal account of her French lover. Kept on a nightstand to be thumbed through, the anthology offers up pieces like Yuki Aizawa’s account of her glamorous, and maybe lonely, Aunt Yumi, whose small Tokyo bar hosts intimate nights full of “champagne flutes stuffed with forgotten cigarettes.” By the end I felt I’d recognize the aunt or bar on sight.

With the book’s thirty-five-and-under constraint, it’s easy to look for themes about growing up. But even if the reader isn’t searching, anybody who has ever felt around for an imagined threshold to adulthood will find flashes of those concerns in these pages. Ian Bardenstein’s “NYClopedia” is an A-Z scatter of thoughts on his life in the city, none of which gets more than six lines. His entry for “grown-up” reads, “Seeing how other people have matured since high school makes me feel undeniably adult. When I was younger, I never thought that one day I would be friends with a teacher.”

In the midst of his tale of a climb in Venezuela, Andrew Bisharat writes, “I’m cynical enough to find my ambitions pointless, but too zealous and insufferable not to blindly pursue them. I often wonder if this feeling dwindles with age as a person realizes he may never stand on top of his personal mountains, and if that reconciliation is awful or not.” As somebody who has never wondered this, I can only assume its truth.

The writers grow up in less explicit ways as well, and sometimes their journeys deal with time as much as space. One woman writes her way to the moment just before she meets her father’s killer. A student visits Ward 86, the San Francisco wing dedicated to AIDS as it emerged as an epidemic, and imagines the death of an uncle he never knew. Years after she envies the breasts of the young Guatemalan mothers, Liz Quin continues to mourn an infant strangled by its umbilical cord. She recalls the midwife wondering whether things would have gone differently at a hospital. Years have made Quin question the mantra—“we’re all human, we’re all human”—that she’d carried in the place where she felt so apart. “How dare I pretend that we are more the same than we are different?” she asks.

In her introductory note, Brisboise writes that more often than not, reading the pieces in her anthology made her want to go to the places they talk about. She is right that this is one of the book’s strengths. Putting it down, the reader is left with images of a snowstorm at sea, a bird’s nest in a defunct Colombian lamppost, the walls of Tangier’s medina. But at its best, the collection provokes a desire not just to visit the places in its pages, but to return to those pages themselves. In “The Human Arrow,” Christian Lewis’s tour of that medina, he writes of his no-plan travel style: “It was certainly more dramatic. In my mind, I was Christopher Columbus.” On arrival, painfully American in a city whose language he doesn’t speak, he has the sudden urge to turn the boat around.

“We become who we are because we figure out what we don’t like,” says Bisharat, the climber. “This is why traveling is really just a vacation from growing older.” But travel, writing, growing up—they’re more aligned than they aren’t. In all of them, becoming who we are is tangled up with figuring out who we are not. Not Columbus, or Indiana Jones. Not the same as those we visit, and also not exceptional. The pieces end up being as much about the people as the places they’ve been, and many are worth revisiting.

Asha Veal Brisebois, ed. The Places We’ve Been: Field Reports from Travelers Under 35. The Places We’ve Been LLC. 400 pages.