This article was produced by WBEZ, Chicago’s NPR news station, and Injustice Watch, a nonprofit news organization in Chicago focused on issues of equity and justice in the court system. Reprinted with permission.

Phillip Merritt’s dementia is so advanced he’s lost the ability to speak. But with the help of his cellmates at Western Illinois Correctional Center, the seventy-one-year-old still manages to get on the phone with his brother every few weeks.

“He has to have someone call me, and then I don’t know what to say to him because he can’t understand anything, so I’ll just talk,” said Merritt’s brother, Michael Merritt, in an interview. “All he can say are two words. … I mean, he’s just gone.”

Merritt’s deteriorating condition makes him a prime candidate to get out of prison under the Joe Coleman Medical Release Act, a pivotal criminal justice reform bill touted by Gov. JB Pritzker and Illinois Democrats as an effective way to alleviate the state’s decrepit prison health care system, reduce the “staggering” costs of caring for ailing people in prison, and reunite families with frail loved ones.

Under the act—named after a decorated Army veteran who died of prostate cancer while incarcerated—Illinois prisoners can request early release if they’re terminally ill and expected to die within eighteen months or if they’re medically incapacitated and need help with more than one activity of daily living, such as eating or using the bathroom.

But a year-and-a-half since the Coleman Act went into effect, an investigation by Injustice Watch and WBEZ found far fewer prisoners have been released under the law than expected, as the medical release process has become mired in the charged politics of criminal justice reform in the post-George Floyd era.

Behind the lower-than-expected numbers is the Prisoner Review Board, a state body appointed by Pritzker and confirmed by the Illinois Senate with final say on medical release requests.

As of mid-August, the board had denied nearly two-thirds of medical release requests from dying and disabled prisoners who met the medical criteria to get out of prison under the Coleman Act—including Merritt.

“I couldn’t believe it,” his brother said. “How could they deny him? He can’t even talk!”

More than half of the ninety-four denied applicants were older than age sixty, and half had spent at least fifteen years behind bars, according to an analysis of state prison data. At least two died in prison, including an eighty-one-year-old who had been incarcerated for more than three decades and was scheduled to be released in 2025. Another man died five days before the board denied his request.

Meanwhile, the Prisoner Review Board has only granted fifty-two medical releases—a rate of fewer than three releases per month on average since board members began voting on those requests, records show.

Advocates say the board is undermining the Coleman Act and forcing ill-equipped prison staff to care for dying and disabled prisoners, even those with families practically begging to take them off their hands.

“Our prison system is now completely overburdened by people who pose absolutely no risk to public safety but are tremendously expensive to care for,” said Jennifer Soble, lead author of the Coleman Act and executive director of the Illinois Prison Project, a nonprofit legal group that represents dozens of medical release applicants.

“From a cost-saving perspective, from a government-efficiency perspective, and truly from a moral perspective, we need to be doing something differently here,” she said.

Donald Shelton, chair of the Prisoner Review Board, declined an interview request, but he defended the board’s record on medical release requests in an email sent through a spokesperson.

“Each case that comes before the board comes with its own set of circumstances to be studied and evaluated by members,” he wrote. “Due diligence is given by the board to every person who sets a petition before them.”

A day after this story was first published, Pritzker defended the board’s decisions in medical release cases.

“The Coleman Act is, in fact, being carried out as it should be,” Pritzker said when asked to respond to Injustice Watch and WBEZ’s reporting at a press conference.

“I’ve encouraged the Prisoner Review Board to do the right thing, to encourage release wherever it’s appropriate,” the governor added. “But we’re not just going to push everybody out the door just because there’s somebody who complains that we haven’t done it the way they would like it done.”

More medical releases could save taxpayers millions

It’s unclear exactly how many of Illinois’ nearly 30,000 prisoners could qualify for medical release. Under the Coleman Act, the Illinois Department of Corrections is required to keep track of that number, but department officials said they don’t have it yet. A department spokesperson said the data would be published by year’s end.

What is clear, from years of scathing reports from an independent monitor appointed by a federal judge, is Illinois prisons are unfit to provide health care for the thousands of aging, disabled and incapacitated prisoners.

Half of the state’s prison medical staff jobs are currently vacant. Prisoners with mobility issues suffer bed sores and frequent falls because no one is around to care for them. Some are even left sitting in their own waste, according to the monitor’s reports.

“Prescriptions go unrenewed, cancers go undiagnosed. In the worst cases, as everyone here knows, people die painful deaths because of the lack of care,” attorney Camille Bennett with the ACLU of Illinois said at a recent hearing on health care in state prisons.

Even this substandard care is expensive. Illinois paid $250 million last fiscal year to Wexford Health Sources, a for-profit company contracted to provide health care to state prisoners, according to state records.

Wexford’s ten-year contract expired in 2021, but the company continues providing care as Illinois seeks new bidders. Releasing more people under the Coleman Act could bring down the long-term cost of prison health care, said Alan Mills, executive director of the Uptown People’s Law Center, a legal clinic in Chicago whose lawsuits against the state led to the appointment of the independent monitor.

“The more prisoners there are who are medically needy, the higher the cost of caring for them, and the higher the bids will be,” Mills said.

Conversely, if the Prisoner Review Board approved more medical releases, the cost savings for taxpayers in the long term could be in the millions, Mills said.

Daniel Conn, chief executive of Wexford Health Sources, did not respond to an interview request. LaToya Hughes, acting director of the Illinois Department of Corrections, declined to comment.

There are other, more immediate savings for Illinois taxpayers if more ailing prisoners were released, Mills said.

A recent government report showed Illinois spends more than $76,000 on average to incarcerate a single person for a year. Experts say terminally ill and incapacitated prisoners are much more expensive to care for. Prisoners whose medical needs can’t be met in prison infirmaries are escorted to and from hospitals by guards. With prisons short-staffed, officers already routinely require overtime pay.

By refusing to release more ailing prisoners, the Prisoner Review Board is also making it harder for prison medical staff to care for everyone else, Mills said.

“What limited resources we have are being devoted to people who are most seriously mentally or physically ill, and that doesn’t leave any health care for anybody else at all,” he said.

At the same time, the overburdened health care system is also blocking more prisoners from getting out under the Coleman Act.

Prisoners must be found qualified for medical release by a prison doctor or nurse before the board votes on their case. But prisoners often wait weeks or months to know whether they’ll qualify, records show. In one case, a prisoner at Illinois River Correctional Center waited 152 days before finding out he didn’t qualify for release, records show.

Prison medical staff have said 240 prisoners who applied were unqualified for medical release. At least a handful of those prisoners lived in a prison infirmary, used wheelchairs, or had terminal diseases like end-stage liver disease; and at least three died in prison, records show.

There are other frail and disabled prisoners who don’t see a doctor on a regular basis, “so there’s no way for the doctors to know about their condition,” Soble said.

Michael Merritt knows the limitations of the prison health care system all too well. His brother Phillip Merritt hasn’t received proper medical treatment in prison for years, he said, and he’s afraid of what could happen as his brother’s dementia worsens.

He wishes the state would let his brother die at home, where his family can take turns caring for him, instead of a prison cell, where he’s unsure whether there’s anyone to properly look after him.

“I don’t know what the problem is,” Merritt said. “They know they can’t take care of him in there the way he is supposed to be taken care of.”

Medical release decisions dictated by politics

The Prisoner Review Board never told Merritt why they denied his brother’s medical release request. Their deliberations happen behind closed doors, and the law doesn’t require them to provide an explanation.

Board chair Shelton said members weigh many factors when voting on medical release requests, but they primarily focus on an applicants’ prior convictions, where they plan to live once they’re released, and testimonies from the victims of their crimes.

An analysis of the board’s decisions shows there’s likely another factor at play: politics.

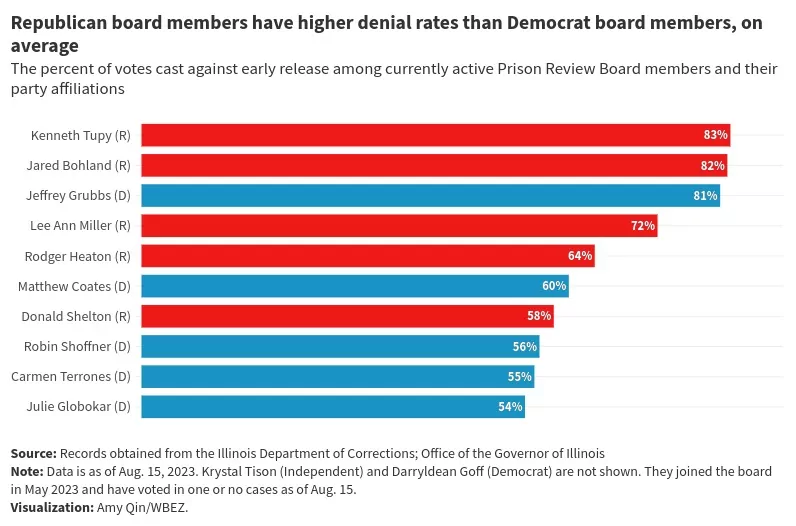

Under state law, the board is required to be roughly evenly split between Democrats and Republicans. The twelve current members include former law enforcement officials, educators, attorneys, and counselors. Pritzker appoints all board members, who are then confirmed by the state Senate.

Medical release requests are decided by panels of three board members; at least two must agree to either approve or deny a request. Shelton said board members are “chosen randomly” for the panels.

But so far, Republicans have cast more votes in medical release cases than Democrats—and they are much more likely to vote to deny those requests, an analysis of voting data shows.

Three out of the four board members with the highest denial rates—Jared Bohland, Kenneth Tupy, and LeAnn Miller—are Republicans. Each of them voted to deny release in more than seventy percent of the cases they heard, and each voted on more than a third of all medical release requests, voting data shows.

Bohland and Tupy, along with Democrat Matthew Coates, were on the panel that denied Phillip Merritt’s medical release request in July. They voted to deny six out of seven requests that day, records show.

A month earlier, Bohland was part of another panel, this time with two other Democrats, when they heard the case of eighty-two-year-old Saul Colbert.

Like Merritt, Colbert developed dementia while serving time for armed robbery. They both also had previous violent convictions, records show; Merritt had a conviction for attempted murder, while Colbert was convicted of murder.

Both had family ready to take them in, and both were represented by the same attorney with the Illinois Prison Project. But the board voted two-one to release Colbert, with Bohland voting against.

“The only difference between those cases was the panel,” Soble said.

Through a spokesperson, Bohland, Tupy, and Miller declined to answer questions about their voting records.

Lisa Daniels, a former board member and a restorative justice practitioner, said she believes some of her former colleagues are ideologically against letting anyone out of prison early.

They “simply believe that a person should complete the entirety of their sentence, no matter the circumstances they present in their petition, no matter how that person may have shown themselves to be redeemed, and no matter (if they’re) no longer a threat to public safety,” Daniels said.

Daniels resigned from the board in January, one of six Democrats to step down or fail to be appointed since 2021. In the past few years, the state GOP has turned the board into a new front in the ongoing debate over criminal justice reform.

Democrats, who have a supermajority in the state Senate, have failed to muster enough support among their ranks to get Pritzker’s appointments through, leaving the board with three vacant seats.

Pritzker declined an interview request before this story was first published.

But in the press conference last month, he expressed confidence that board members “are people who care deeply about criminal justice reform (and) who care deeply about making sure that we’re being fair to prisoners—and to the community in which we’re releasing people.”

In a statement sent in response to follow-up questions, Pritzker’s spokesperson said “there are undoubtedly improvements that should be discussed among stakeholders and the General Assembly as the law continues to be implemented.”

Coleman Act has ‘failed to live up to its promise’

The day Pritzker signed the Coleman Act, its main sponsor, state Rep. Will Guzzardi, D-Chicago, said in a press release the law would transform Illinois’ prison system and allow families to properly say goodbye to their loved ones.

“I’m sorry we couldn’t afford this mercy to Joe Coleman, but I’m proud that we’ll be able to do so for hundreds of other Illinoisans,” Guzzardi said.

Criminal justice reformers celebrated the Coleman Act as a model for other states to follow. In a report last year, FAMM, a prominent national advocacy group, said the Coleman Act was one of the strongest “compassionate release” laws in the country.

But so far, the act has “failed to live up to its promise,” said Mary Price, FAMM’s general counsel and the report’s author.

Advocates want lawmakers to institute several changes to the Coleman Act to encourage the Prisoner Review Board to release more people.

Lawmakers should require board members to visit prison infirmaries to see firsthand the state of prison health care, advocates said. The board should also receive more training on how to evaluate the medical conditions of prisoners applying for release.

Advocates also want the state to provide prisoners who are applying for medical release with an attorney to argue their case. Guzzardi said he’ll advocate for funding for that in the upcoming fall legislative session.

Lawmakers should also allow prisoners to reapply for medical release sooner than currently allowed, said William Nissen, an attorney who represents prisoners pro bono, including on medical release requests.

Prisoners denied medical release currently have to wait six months before they can reapply, unless they get a special exemption from the board. Shelton has only approved three out of ten requests so far, according to figures provided by the board’s chief legal counsel.

“If you’re representing a terminally ill person, then a large part of their remaining life is gone before you can even apply again,” Nissen said.

Nissen said lawmakers should also require the board to explain why they denied a medical release to “instill a certain amount of discipline in the decision-making process.” If board members have to articulate their reason for denying someone release, maybe they’ll reconsider the decision, he said.

Phillip Merritt’s attorney is in the process of refiling his medical release request. His brother Michael doesn’t know whether he’ll get out this time. And he hasn’t been able to reach Phillip in three weeks—the cellmate who had helped facilitate the calls was apparently transferred.

But he’s certain he and his family can give Phillip a more humane send-off than any prison could.

“At least he could go peacefully,” he said.

WBEZ reporter Alex Degman contributed reporting.