On Sunday, March 19, South Side Weekly hosted Brick by Brick, a community engagement event that invited local residents to reimagine their communities, and panel discussion with community advocates actively involved in creating spaces on the South Side. The event took place in Bronzeville at the offices of civic media organization City Bureau.

As dozens of attendees ate vegan soul food from Soul Vegan, they were divided into five groups for an interactive urban design challenge. Each group was given a scenario by the Weekly’s engagement team that explored how everyday conditions in our community can be improved and the systems that can enable change. Prompts included imagining a grandmother advocating for more walkable sidewalks, a local grocer closing its doors, and a group of residents tasked with designing a park from scratch, and got attendees thinking about their community, seeing things from each other’s perspective to evaluate and problem solve.

“I do think town halls (are) a good forum, because there’s a certain sense of accountability when you’re in a room and you’re talking about something and everybody can hear you,” said panelist Cecilia Cuff, founder of South Side Sanctuary. Her group was discussing the scenario of a grandmother who struggles with a sidewalk riddled with cracked pavement, potholes and sparse street lights. In the scenario, a grandmother has tried to get the local alderman’s attention to no avail, and a decade has since passed.

During a panel following the activity, Cuff spoke about her work with the South Side Sanctuary, an ongoing effort to bring a new community gathering space to an empty lot at 4702 South King Drive. “There’s been an empty lot there for a few decades now and we were able to convince the city of Chicago to allow us as a group of young people to transform that lot into a multi-use space that will offer health and wellness training (and programming), arts and culture programming, innovation and entrepreneurship like farmer’s markets,” Cuff explained to the crowd, noting the concentration of empty lots particularly on Chicago’s South and West Sides.

“We’ll be able to activate that space and use it as a case study. When we’re able to activate empty spaces as a community, we create spaces that not only create safer communities, but additionally are able to activate space that makes the whole corridor busier.” Also a co-owner of Bronzeville Winery and founder of The Nascent Group, a hospitality design agency, Cuff has a background in development, which she brings to her work.

In her small group, Cuff spoke to the challenges of town halls firsthand in progressing her own efforts. “Aldermanic town halls aren’t as well attended as they probably could be. I only started going to town halls because we had a project and we wanted to be able to communicate or present at the town halls,” she said.

This testimony led the group to consider the town hall model, and the purpose of why people attend.

“Even though a lot of the issues seem trivial, it means a lot to the people in the neighborhood,” said City Bureau documenter and reporting fellow Ahmad Sayles on his experiences documenting police district council meetings. “No matter if it’s a small number of people complaining, the squeaky wheel gets the oil. You stand out a lot more when it’s a meeting that everyone wants to breeze through and you’re like ‘No, I actually have a problem.’”

The conversation included other means of putting these issues on the city’s radar, including through block clubs, calling 311 and potentially escalating to the Office of

Emergency Management & Communications as possible solutions to the sidewalks issues.

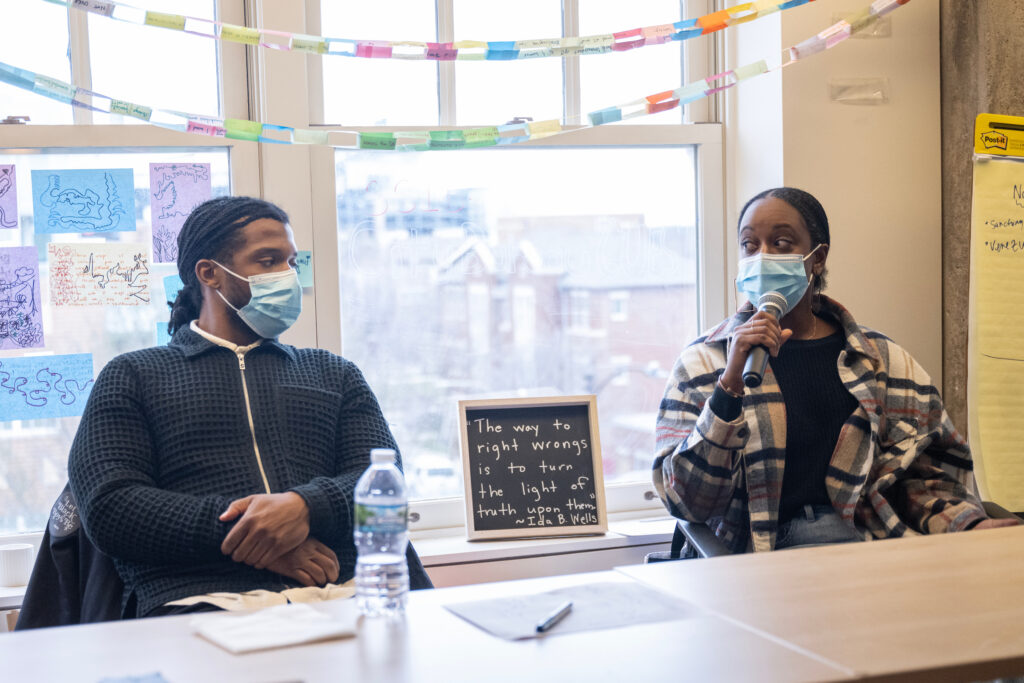

Led by journalist and critic Anjulie Rao, the day’s panel featured Cuff, urban farm Sistas in the Village co-founder Nyabweza “Bweza” Itaagi and #LetUsBreathe Collective co-founder Damon Williams.

“When we talk about urban design, it’s a catch-all phrase. It’s architecture, sidewalks, parks, pollution management, zoning…it’s a lot of different things,” Rao said during the panel introduction. “What’s really interesting to me is that all of our panelists today are actually thinking about this idea of urban design and planning in a very different way. In a way that I think also acknowledges the fact that urban design is not just the thing that exists. It’s all of the policies that were designed to ensure that our city looks the way it looks now. I think that things like redlining are as much carefully urban designed as the Harold Washington Library.”

Williams’ background includes being an artist, abolitionist and self-described “movement maker.” Spawning in 2016 from the Freedom Square occupation, the #BreathingRoom space originated as community center by the #LetUsBreathe Collective and counter effort against divestment in North Lawndale. Currently it is located at 1434 West 51st Street in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. Beyond being a community center since 2016, the Breathing Room has hosted a farm and garden for the last four years.

“The Let Us Breathe Collective has been in existence since 2014 and started at the intersection of cultural space and liberatory resistance,” Williams said. “Whether it’s in a park. Whether it’s downtown. Whether it’s in Ferguson. Whether it’s across the street from the Chicago Police black site.” Williams emphasized the importance of ensuring space for the movement for Black liberation while being “emergent, organic, experimental and non-traditional.”

Bweza Itaagi started Sistas in the Village in 2020 and also serves her community through Grow Greater Englewood, whose “primary focus is to repurpose some of the vacant spaces within the community into more nature centered gathering hubs,” Itaagi said. “We are working to repurpose an almost two mile long vacant, elevated train line that hasn’t been in use since at least 1960. That is really just the story of a lot of spaces around it.”

Itaagi explained shifting demographics and industries led to the creation of such vacant spaces. The influx of Black residents during the 50’s and 60’s coincided with many businesses and manufacturers relocating. “There used to be a very rich, active, light manufacturing industrial use in the area. And then as the demographic shifted. It became more Black as businesses were leaving. That community was left with a lot of just vacant spaces that are still vacant to this day.”

“Primarily, the work that we do is to come up with community solutions to collectively decide what is the best use of these spaces and how it will help us live healthier, more robust lives.”

Itaagi continued, “We are an urban farm, about half an acre sized farm, on the corner of 58th and Ada. We focus on growing crops that are really central to the African diaspora. I am half Ugandan. I’m really passionate about just reconnecting us with the land and reminding us that all of us thrive as a community when we’re closer to the land when we’re connected as individuals.”

The remainder of the panel focused on how each individual panelist realized the presence of a need and unmet gaps in their communities. Cuff recounted first seeing income inequalities through working in the service industry. She also saw how climbing the ladder in hospitality was possible to close generational wealth gaps, as one could eventually go from being a lower position to becoming a chef or opening a restaurant.

She says she applied this same hope of vertical mobility, despite inequities, to her work in urban design. “It just comes from hard work,” Cuff said. When I think about development, I think of how do we take empty space and how do we create hope in our community,” she said. Cuffs sees redlining, empty storefronts, highways blocking certain communities and other disparities as ways to remove hope. “When you’re frustrated when you don’t see a through line or a path, that takes hope away. My career path has always been counteracting that stop line and creating that hope to say ‘yes, I actually can.’”

Cuff’s work includes beautifying spaces through cleaning up trash, rejuvenating business corridors to increase foot traffic to businesses, and rewriting many common narratives about the South Side. She wants to create an environment where North Side residents can visit South Side Sanctuary or any business in the area and leave saying “I went to the South Side and I was okay.”

Williams spoke on realizing the need for the Breathing Room through experiencing the aftermath of the death of Mike Brown in Ferguson, MO. “We, without knowing that we were about to become an organization, found ourselves in a nexus of folks saying ‘we want a world without prisons and police and we want a new infrastructure of social systems to take care of people,’” Williams said.

He emphasized that these ideas are not inherently new, having been introduced in the mid-20th century by Black liberation movements such as the Black Freedom Movement and Black Panther Party.

“In 2014, 2015, (I was) seeing that there was this overlap of cultural community and burgeoning political activism that was connected,” Williams continued, noting activists such as Rick Wilson, Asha Ransby-Sporn and Jamila Woods. All of these involvements led him to starting Respair Production & Media which has been “archiving, documenting, learning from creating conversation with space makers, movement builders all around the city, and around the country and the world.”

Itaagi first saw the need for urban design and incorporating nature through her childhood growing up in Denver, Colorado. When cannabis was legalized in 2012, she saw her hometown change. “There was this rush of people moving to displace all the Black, brown and Indigenous communities, and creating a new Denver,” she said. She says the displacement of minority communities led to people moving to food deserts, piquing her interest in fresh food. “That drew me to Chicago…I went to DePaul to study sustainable urban development because I was really trying to find these answers to how can a city grow and expand allow people to come in, while still looking out for the folks who have been there, and especially marginalized folks.”

“That’s when I started understanding how land is really central to the conversation. When we’re talking about urban development, it’s not just about building structures, but there needs to be a way of just really connecting with the Earth as a living breathing entity that we are privileged to live on.”

To stay updated on South Side Weekly events, follow us on social media.

Michael Liptrot is a staff writer for the Hyde Park Herald and South Side Weekly.