Many of us know about the Harlem Globetrotters, a South Side all-Black basketball team, and Abe Saperstein, its Jewish, Chicago-based promoter. The Globetrotters had its impetus at Bronzeville’s Wendell Phillips High School (now William Phillips Academy High School) and went on to become a worldwide sensation that entertained millions. Saperstein championed the three-point shot, a staple in modern basketball.

Saperstein was a fixture in baseball’s Negro Leagues. He also elevated Black folks in positions of authority within his Globetrotter organization, and assisted Olympic champion Jesse Owens financially when he fell on hard times. But he also leaned into some of the racial stereotypes of the day and used his team to assist the U.S. government by spreading propaganda in the aftermath of the bad publicity America received amid the 1957 desegregation of a Little Rock, Arkansas high school by playing exhibition games all over the world.

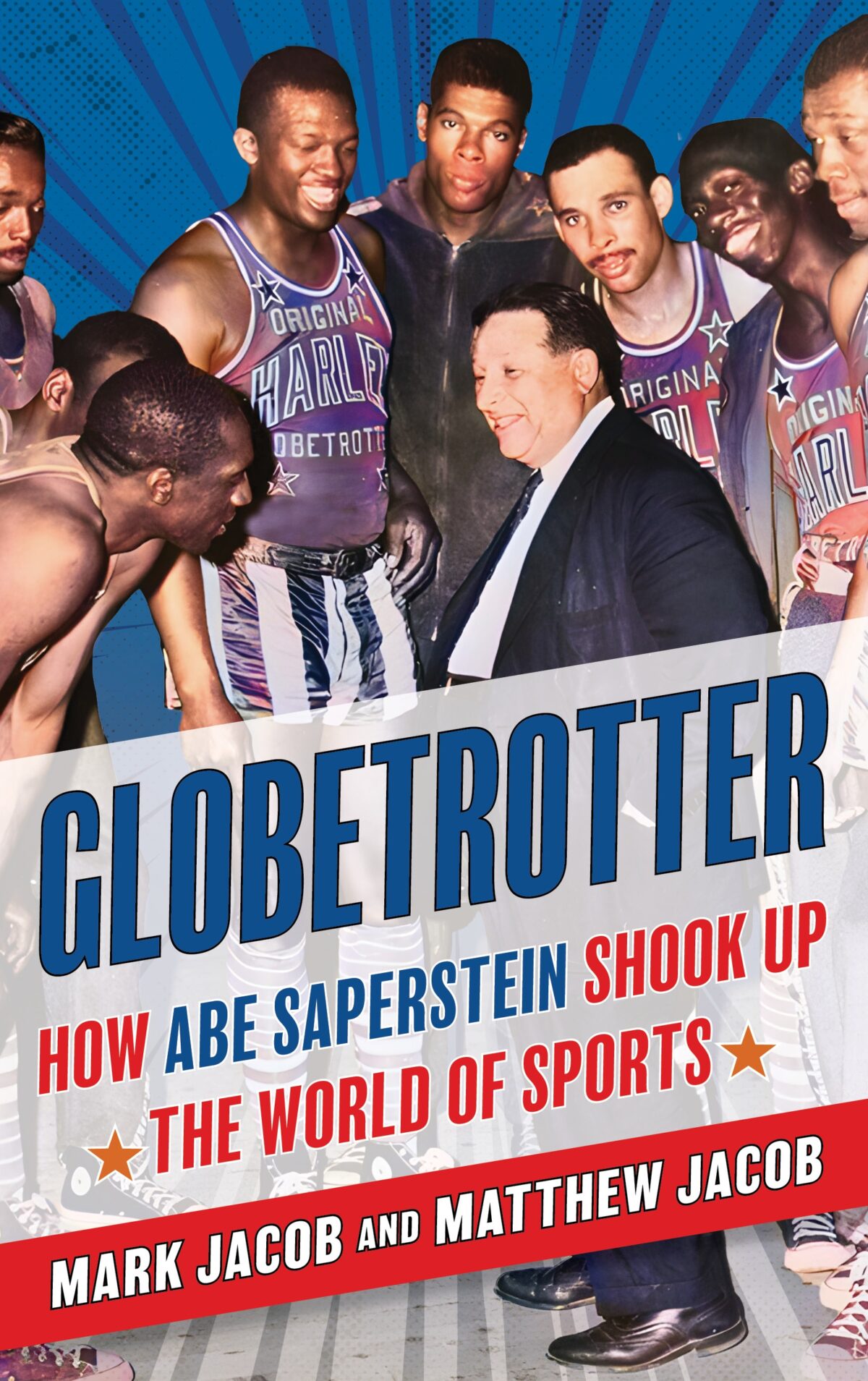

Journalists and brothers Mark and Matthew Jacob’s book, Globetrotter: How Abe Saperstein Shook Up the World of Sports , isn’t a hit piece. It’s also not sportswashing—the practice of utilizing sports to divert attention away from unethical behavior—even though Saperstein was himself guilty of it.

Some of Saperstein’s players, budding hoops iconoclasts, and, perhaps most notably, the Black press including the Chicago Defender, often called Saperstein out for the minstrel vibes given off by the Globetrotters. Even as a kid who couldn’t quite formulate what I was watching at the time, I knew something wasn’t right.

The type of respectability politics where Black men are forced—or in some cases are willing participants—to be subservient to white people via comedy in order to not upset them was often a common theme, as the Globetrotters entertained generations of people worldwide:

When Bill Russell of the University of San Francisco emerged as a huge talent, San Francisco Examiner columnist Curley Grieve wrote that it was “generally assumed” that Russell would join the Globetrotters upon graduation. But the six-foot-ten Russell wasn’t so sure, unless Saperstein offered a deal too huge to reject. “I don’t want to be a basketball clown,” Russell said. “I like to laugh. But not on the court.”

Despite comments like that, Saperstein courted Russell with determination. When Russell’s college team was in Chicago for the DePaul Invitational Tournament in December 1955, Saperstein met with him privately and, according to Russell, tried to sell him on the “social advantages” of being a Globetrotter. Russell later wrote that he was put off by the approach but did agree to a second meeting that included Russell’s coach, at Saperstein’s suggestion, “to keep everything on the up and up.” Russell said Saperstein annoyed him further at that second meeting by discussing his money offer only with his coach, without including Russell. To Russell, the message was: “As one Great White Father to another Great White Father this is what we’ll do for this poor dumb Negro boy.”

Many of the supporting characters in the book are Black folks who held important roles in making the Globetrotters the global brand they are today, such as Inman Jackson, a longtime Globetrotter who eventually became Saperstein’s best friend. The authors dedicated the book to Jackson, who was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2022.

The Jacob brothers sat down with the Weekly to discuss Abe Saperstein’s innovations, his business acumen, the conflicting views his Black players have of him, the press’s role in shaping America’s views regarding Black people in sports, and how the two tackled his legacy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why a book about Saperstein? Also, why tell the full story? There’s been so many books. Even before I was told about your book, I had seen the Vice Sports documentary.

Mark Jacob: Matt lives in Arlington, Virginia. I live here in the Chicago area, and, you know, we’ve written a book before together, and we stay close, and just because we had the same interests…we were trying to find a book project to write together. A friend of ours suggested and said, ‘Have you thought about Abe Saperstein?’ and when we started looking into it, we were just amazed by how much we didn’t know. I mean, we knew the Harlem Globetrotters angle a little bit, but we didn’t know anything else. We didn’t realize he pioneered the three-point shot in basketball. For example, all his activities with the Negro Leagues and his promotion of Satchel Paige and his dealings with the State Department to promote Americanism during the Cold War. We were just shocked by how much we didn’t know, and so we started diving into it. As far as that Vice documentary, I thought it was pretty bad, actually. I mean, it was. The thing about it is they melded eras because Abe Saperstein died in 1966 and a lot of that reporting they had, and the interviews they had were about stuff that happened after Abe died.

Matthew Jacob: I think Mark summed it up well. Saperstein was a complicated figure and we wanted to paint a very accurate portrait of him that we felt was textured and not just kind of this good guy-bad guy dichotomy.

Growing up, what was your view of the Globetrotters? Because with me, I saw their shows, and I saw them on Scooby Doo growing up. But as a kid, I couldn’t contextualize what’s going on. But years later, I’m like: Yeah, there was a minstrel vibe going on—and you all get into a lot of that. And in the book, where you have Black players and Black folks who on one end thought he was a great guy, and on the other end, folks like [Black sportswriters] Wendell Smith and Lacy J. Banks saw what they thought he was doing and called him out on it.

Matthew: Yeah, I had kind of a similar reaction as a kid. You know, they were on Saturday morning TV; they were front and center. I didn’t physically go see them, but I remember they were on CBS Sports, Wide World of Sports on ABC so you would see them on TV. They had a high profile but what you don’t fully appreciate until you read into [the book] and really do a lot of research, is some of the routines, some of the gimmicks that were going on. The dice game in the corner while the game was going on, and how that plays into white stereotypes of what young Black men are into. Even Saperstein, late in his career, told a news sports editor at one point, “we’ve revamped the show in a way that we’ve gotten rid of a few routines that fans had told me they didn’t like, that they didn’t feel reflected well on the Black community.” You know, he did some things that definitely helped move the ball forward. He was a co-owner of the Birmingham Black Barons and helped to get young Black stars like Satchel Paige’s—an older Black star—into the major leagues. By the same token, this is a guy who promoted two teams that made some people wince. And by today’s standards, we would go: “Whoa, wait a minute….”

Mark: I saw the Globetrotters once as a kid and, you know, Matt and I saw them again when we were doing research for the book. Being a white kid growing up in suburbia, I didn’t critically think it was offensive or anything. I just thought they were a comedy act. And it’s really complicated. I can understand why Black people didn’t want one of the primary images of Black people in the United States to be clowns at a basketball court, but at the same time, you know, Abe was developing a very profitable product because other people were more racist than he was.

One of the things that blew me away as we were doing the research was this white perception in the middle of the last century that Black people weren’t good at team sports. There was this idea that Black people, Black players, were athletically, physically endowed, but they would choke in the clutch. There were all these stupid misconceptions that in the modern world seemed like stupid misconceptions; seemed utterly ridiculous. But back then, it was considered to be an accepted thing in white circles, at least. And to some extent, to a great extent, really, Abe Saperstein explored this mess, and I think he should get some credit for that.

What was it like writing about how Saperstein was great in some areas, and completely terrible in others, and went along with what was going on at the time?

Matthew: Yeah, I think what helped Mark and I very early on; [we] sort of had some good conversations about what our objective was. And you know our objective was to bring to life somebody that many people, even those who were very interested in sports, knew little or nothing about. But our objective was not to take aim at someone. It was also not to polish someone’s image. We really wanted to look at everything we found, pull apart the news articles, the coverage, the research, look at our interviews that we did, and let the cards fall where they may, and feel like we’re telling an accurate story and not get caught up. Mark was talking with family members, several of them, and they’re very invested in this man. He is this larger-than-life figure that they either grew up knowing or grew up hearing about. And so, I think it was a delicate situation for them. They wanted to feel like we were being very fair, but to us, fair was letting the facts and the information speak for itself. And I think that’s something we made every effort to do.

Mark: The interesting thing was that there were a lot of people who wanted to be irrationally positive about Abe and a lot of people who wanted to be rationally negative about Abe. And the truth is somewhere in between, obviously, and we were really honest with Abe’s descendants. We talked to grandkids of Saperstein, and they had shared information with us and memorabilia and their stories, and we were grateful for that, and I do give them some credit for continuing to cooperate with us even though we made it clear from the get go that we were not going to hide any facts that we thought were important, positive or negative, about Saperstein. And I mean, it goes a little bit to the question of whether you judge somebody and some historical figure by their times or by modern standards. But at the same time, the more we got into it, the more we realized that there was another side to it, which was that he helped explode a lot of myths about Black athletes. He helped get Black athletes into major sports when they were being excluded. He gave responsibility to Black people. I gotta say that almost nobody knows that Abe Saperstein pioneered the three-point shot in basketball. This is a great achievement. This transformed the sport. I mean, we see it every day. You know how game three of the WNBA Finals was won last night? It was won by a three-point shot.

Knowing that [Saperstein] pioneered the three-point shot, and that in the NBA game there isn’t a big man that’s relevant that doesn’t have some type of outside shot, let alone a three point shot, what do you think Saperstein—knowing his battles with the NBA and now seeing that most centers now have a three-point shot—would think?

Matthew: Yeah, maybe it’s a case of where Saperstein lost the battle but won the war because the game did change. But in some ways, like you say, Evan, that’s in ways that maybe he didn’t expect or anticipate it. It also reminds me of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, late in his career, telling a sports writer that he realized, even though he’s this big man, he’s right dead center in the action working in the paint. He knew he needed to work more on his ball handling. And the person that inspired him to do that was in one of the Globetrotters movies.

Mark: When you think about the Globetrotters and their behind-the-back passes and no-look passes and alley-oops and all kinds of the tricks they pulled, and you also combined that with Saperstein pioneering the three-point shot in the American Basketball League, I think you could make an argument that Saperstein is one of the most influential people in what the NBA looks like today. The NBA back then was really kind of boring. I mean, and it wasn’t just flashy. [The NBA] kind of shut Saperstein out to a large extent. They just were sports purists and they thought he was simply a showman. But the modern NBA, I think, has shown that you can be both at the same time: great athletes trying to win, but also being entertaining.

In the book I think there’s these different images that go back to the same point about what we always see when management and players are deciding what a player is worth. In a lot of cases, fans take the side of the owner or management over the player, and the player is always seen as greedy. What was it like to see those conversations come full circle?

Matthew: Yeah, one interesting comment about that and there’s a point in the book is where Abe likes to be that guy after a big game or a big win, to say: “Hey, here’s $100. Here’s $50.” And [Globetrotter] Marques Haynes at one point says: “Just put it on my salary.” And, of course, as we explain in the book, eventually things came to a head there, and Marques Haynes got very estranged from the team, and eventually left and felt like he wasn’t being treated fairly, I think, for reasons that people can understand. And then, on the other hand, in baseball, as a business agent for Satchel Paige, he was actually helping to enable Satchel Paige to walk out of contracts, right? I mean, in the mid-1930s, Gus Greenlee [team owner] of the Pittsburgh Crawfords was furious when Satchel Paige left to go play for a semi-pro team in North Dakota. Well, it was a team that was going to pay him more money and Saperstein worked out the deal. So Saperstein was on both sides of that contractual salary negotiation dynamic that was kind of interesting.

Mark: The thing we point out in the book, clearly, in that era in all sports, Black or white, players were underpaid compared to today, and the owners had all the leverage. And so it just was a different dynamic. We were really trying to examine how fair [Saperstein] was to his players or how unfair he was to his players, and you hear from both sides. You have some players who really had great testimonials to Abe and talk about how generous he was…but others thought he was tough to deal with. I think at least I came away with the impression that it was more of a manager or an owner-player dynamic than a white owner-Black player dynamic; that it wasn’t as much of a racial dynamic as a capitalist dynamic.

You all did research with a lot of newspapers, and how you read how Black people were described in a lot of newspapers. What was it like to see that, and thinking, as two former editors saying: This got past everyone in the newsroom?

Mark: I guess I wasn’t surprised because I read a lot of newspaper clips, and I know how racist American newspapers were back then, and how society was, and that’s what it was reflecting. What’s really amazing is that sometimes these sportswriters thought they were complimenting the Globetrotters when they were actually insulting them. I guess this casual racism of that era still stunned me sometimes because of the pervasiveness of it.

Globetrotter: How Abe Saperstein Shook Up the World of Sports by Mark Jacob and Matthew Jacob. 320 pages. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2024. $35. Hardcover.

Evan F. Moore is an award-winning writer, author, and DePaul University journalism adjunct instructor. Evan is a third-generation South Shore homeowner.