This story was produced by Injustice Watch, a nonprofit newsroom in Chicago that investigates issues of equity and justice in the Cook County court system. Sign up here to get their weekly newsletter.

The scientist was on the witness stand explaining how marijuana affects the human body. Forensic toxicologist Jennifer Bash was called by the state as an expert witness, as she had been dozens of times before. But this case in DuPage County wasn’t the typical stuff of courtroom drama; there were no dead victims or tearful relatives in the gallery and no prison time in the cards for the defendant. He was charged with a misdemeanor DUI for allegedly driving under the influence of cannabis.

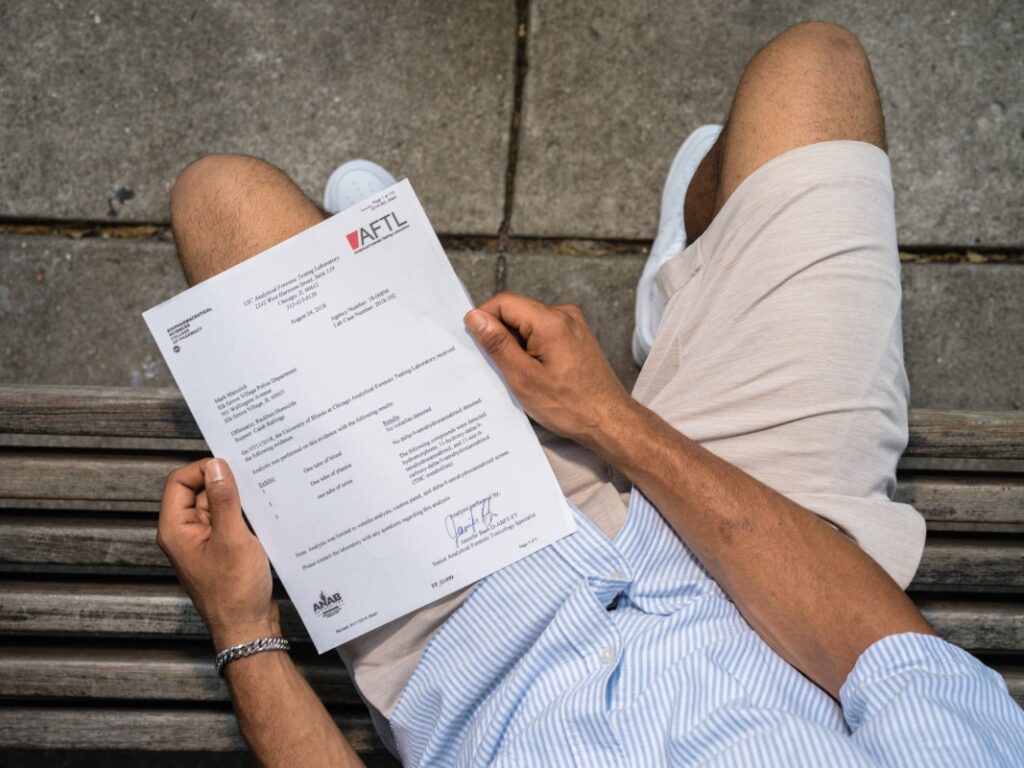

Late one night in 2017, Lombard police officers pulled over thirty-two-year-old Dwan Thompson for going seventeen miles over the speed limit. Officers suspected he was stoned, reporting he had watery eyes and a blunt in his cup holder. After conducting several field sobriety tests, officers still suspected he was intoxicated, so they arrested him and asked for a sample of his urine back at the station. The sample was sent to Bash’s lab at the University of Illinois Chicago, where she tested it for cannabis.

As he watched Bash testify, Kevin McMahon—who was less than four years into his legal career as a public defender and hadn’t had much experience challenging scientific evidence—grew annoyed, then outraged.

Leading up to the trial, McMahon had several lengthy phone calls with Bash in an attempt to understand her analysis of Thompson’s urine. “After two to four conversations I still felt confused by the lab report,” McMahon told Injustice Watch. The report didn’t specify whether Thompson was over the legal limit for tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC—the component of marijuana that gets people high. “I was like OK, the way she’s describing it this guy is guilty…” and yet “I was still on the fence about whether to advise him to plead because I still didn’t understand if he was guilty,” McMahon said.

He reached out to a toxicologist at another crime lab for a second opinion. “And that’s when I knew I wouldn’t be pleading this out.”

Bash had extensive credentials: a master’s degree in organic chemistry, more than a decade of professional experience, certifications from the American Board of Forensic Toxicology and the Illinois State Police. Her lab at UIC was accredited to international standards. Bash had tested blood and urine for alcohol and drugs “thousands” of times and testified as an expert witness more than 80 times before that day, she told the judge.

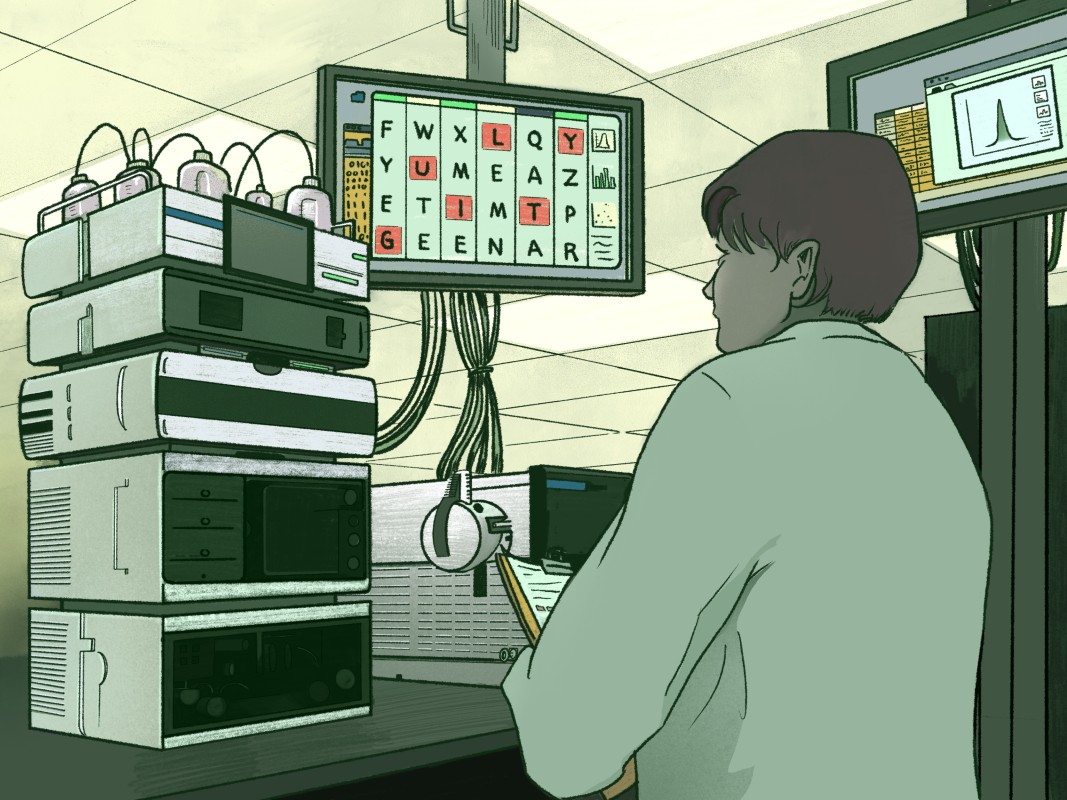

At trial, McMahon expected Bash to say she didn’t find any THC in his client’s urine, because the drug doesn’t show up in urine. Its metabolites—chemical byproducts created as the body processes drugs and other toxins—can be found in urine days, even weeks after last use, making them useless for determining whether someone is high while driving.

On the stand, Bash, in her early forties with short hair dyed reddish pink, used complicated scientific terms to describe how the body processes marijuana and the steps she took to analyze urine. She explained how the body flushes the THC out with a “complex molecule called glucuronide” attached. She described how she performed chemistry on Thompson’s urine to separate that complex molecule from the THC and quantify how much of it Thompson had in his system.

Judge Anthony Coco, struggling to keep up, interrupted Bash. “You are saying glucon—?” Bash spelled it out: “It’s g-l-u-c-u-r-o-n-i-d-e.”

The prosecutor continued her questions, driving Bash to her overall point: The metabolites of marijuana in Thompson’s urine were ultimately the same as the drug. By then, McMahon had done enough research to know that wasn’t true.

“I object,” McMahon said. “The scientific community does not treat these compounds as if they are the same.”

“I am going to overrule your objection,” the judge said, “but I am not understanding.”

“She should not be allowed to testify to this,” McMahon objected again. But the judge wasn’t convinced.

Next, McMahon tried to fight Bash’s testimony with his own expert—a forensic toxicologist with decades of work experience in the Illinois State Police crime lab who had testified more than 100 times for the state and only one other time for the defense.

He confirmed THC and its byproducts in urine are not the same thing and said the State Police lab doesn’t test urine for DUI-cannabis investigations. McMahon was hoping to make the judge understand there was no THC in his client’s urine until Bash converted metabolites back into the drug. But it was futile.

“This was a very interesting trial,” the judge said in a sincere tone after both sides finished their closing arguments. He found Thompson guilty on one count of speeding and not guilty of impaired driving based on the field sobriety tests. That left only the DUI-cannabis charge hanging on Bash’s lab analysis.

“As to the charge with all the science, a big reason I went to [law] school was because I stunk at math and I stunk at science,” the judge said, and announced he would take some time to review the transcript before ruling.

A month later the judge found Thompson guilty and sentenced him to court supervision, a two-year slog with hundreds of dollars in court costs stacking on top of the loss of his driving privileges, and many ninety-mile round trips from his home on the Far South Side of Chicago to the courthouse in Wheaton.

McMahon remains convinced the judge made the wrong call by discounting testimony from the State Police toxicologist. But he said he was more stunned by what Bash said in court, and how confidently she testified.

Though Thompson appealed, he lost. The appellate court ruled it had no legal standing to override the trial judge’s decisions about expert witness credibility. As that ruling came down, McMahon’s office was flooded with more clients facing DUI-cannabis charges based on Bash’s urine testing—mostly low-level misdemeanors typically resolved through plea deals.

“We felt forced to dig deep,” McMahon said. “You have so many people you’re representing accused of things they’re not guilty of. … I just knew we gotta do something, we can’t just plead those out.”

Thompson, who otherwise had a clean driving record, is still baffled by his case. Regardless of what Bash said about his urine, he said in an interview with Injustice Watch, he knew he wasn’t high when he got behind the wheel of his black Nissan Altima the night he was pulled over.

He’d driven out to Joliet with a friend to catch his brother’s concert. Before the show, he smoked half a blunt. He was saving the other half for later and left it in the cup holder. By the time he got on the road after the performance it had been several hours since he’d smoked. After years of experience, he said, he knew his limits with marijuana and he was good to drive.

It would take more than six years for Thompson to be exonerated, along with more than a dozen other DuPage County defendants who had been convicted of low-level DUI-cannabis charges with the help of Bash’s lab work and testimony.

By then, Bash would resign and UIC would shut down her lab right as an accrediting agency’s audit uncovered a range of unacceptable problems in its operations. Prosecutors’ offices in some of the seventeen counties for which the lab provided testing would also issue disclosures to defendants about Bash’s “inaccurate and unqualified testimony.”

In a months-long investigation—including more than forty-five Freedom of Information Act requests, more than 100 interviews, and a review of some 8,000 pages of public records—Injustice Watch found more than 2,200 cases in which body fluids were tested for THC by the UIC lab between 2016 and 2024. In addition to improperly testing urine for DUI-cannabis investigations, these sources indicate the lab was for years unable to differentiate between legal and illegal types of THC in people’s body fluids. Worse, internal records examined by Injustice Watch suggest the lab was aware of some of the problems in its testing since at least 2021 but continued to perform tests and report results to law enforcement, mostly in DUI cases. Bash, meanwhile, repeatedly testified about the lab’s findings in inaccurate and misleading ways.

“I take great pride in my work and have always conducted myself ethically,” Bash said in written responses to Injustice Watch questions. “It is deeply upsetting to be falsely accused.”

Injustice Watch also found university officials charged with overseeing the lab were focused on the lab’s financial performance, and not on the quality of its scientific work. According to internal emails, officials’ eventual decision to shut down human testing at the lab came as a result of its failure to generate revenue.

UIC officials declined interview requests from Injustice Watch but recently issued an internal investigation report exonerating themselves from oversight failures. The report concluded the lab’s methods were “at all times appropriate and met accepted scientific standards” and none of its analysts “knowingly provided false testimony in criminal proceedings.”

The investigation was conducted by outside attorneys specializing in business emergencies, class action defense, and white-collar crime. In May 2024, the lab sent a letter to prosecutors in more than a dozen counties reporting one problem in its testing methodologies going back years, but the lab did not report how many cases were affected or issue any corrected lab reports.

To date, the University of Illinois officials have not notified any defendants the lab’s test results of their body fluids may have been wrong. While Thompson’s record was cleared after years of legal battles, defense attorneys estimate hundreds of other people are still dogged by criminal convictions based on the lab’s work and Bash’s testimony. Some are still awaiting trial on DUI charges stemming from her work. At least two people are serving prison sentences.

The Injustice Watch investigation reveals lax oversight over forensic labs in Illinois, which has a long history of wrongful convictions based on junk science. Despite recent reforms to improve the quality of forensic science, the state is not prepared to stop another crime lab from going rogue.

UIC’s Analytical Forensic Testing Laboratory opened in 2004 when the Illinois Racing Board began using the university to test racehorses for illicit drugs. Bash began working at the lab in 2015, taking a $31,000 pay cut from her prior job as a forensic toxicologist with the Illinois State Police.

By the time she began working there the lab had half a dozen full-time employees, an annual budget of $1.5 million and was testing up to 20,000 horse samples annually. It received coveted accreditation from ANAB, the National Accreditation Board of the non-profit American National Standards Institute. But the horse racing industry in the state was in decline amid the rise of Internet-based gambling options; two of the state’s four racetracks closed in 2015. The UIC lab was looking to pivot.

In her written response to Injustice Watch’s questions, Bash said she took the job at UIC because building up the lab “was a great career opportunity.” At the time she started, Bash wrote, “no one at the lab had experience conducting human testing.”

According to her hiring documents, Bash’s job duties included helping find “state and private agencies which require forensic toxicological analysis in humans to … assist in bringing their business to our laboratory.”

As one of the University of Illinois’ “self-supporting units,” the lab had to cover its own operating costs through selling its services and obtaining grants. According to university policy documents, such independent units are expected to support their teaching, research, public service, or economic development missions and to operate like a business “with one important exception: a self-supporting Fund must break even over time. The Fund should not generate a profit or incur a deficit.”

Bash told Injustice Watch she “wasn’t told anything regarding revenue goals.”

The lab was housed in a low-slung concrete building on Harrison Street, inside the Pharmaceutical Sciences Department at the UIC College of Pharmacy. Yet Injustice Watch could find no evidence anyone at UIC or the broader university bureaucracy knew much about the scientific work happening there. The university’s lawyers confirmed this in their recent internal investigation report, which emphasized officials were “unaware of any of the allegations” against the lab as late as March 2024.

Bash’s boss, lab director A. Karl Larsen, was a seasoned lab administrator. They had worked together at one of the State Police crime labs in the early 2000s. A waiver of open job search procedures was requested for Bash’s hire, describing her as “very qualified as a forensic research specialist” with fourteen years of experience.

Larsen declined Injustice Watch’s request for an interview but said through his attorney he “stands behind his work and the work of the Lab.”

As Bash got the UIC lab’s human testing services running, the years-long battle to legalize marijuana in Illinois achieved a major milestone. In the summer of 2016, possession of small amounts of cannabis was decriminalized, and the state legislature also amended the impaired driving law to include specific reference to cannabis.

There are two ways to be guilty of DUI—by failing field sobriety tests or having certain quantities of alcohol or drugs in your system. Regardless of someone’s ability to walk a straight line, blowing 0.08% or more on a breathalyzer can result in a DUI conviction.

Lawmakers sought to create a similar legal limit for cannabis. The problem, though, was a lack of scientific consensus on how much THC in the body equals impairment. Even more than alcohol, THC affects different people differently, depending on body size, frequency of use, and other individual factors. To make matters more complicated, there are no breath tests to determine cannabis levels in the body.

By the time Illinois lawmakers were puzzling over the problem, several states had DUI statutes that explicitly referenced cannabis, and most of them had a zero-tolerance policy. The states that did set legal limits opted for 5 nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood or less—a limit unsupported by science but tolerable for law enforcement.

When lawmakers initially passed a bill with a higher limit, then-Gov. Bruce Rauner vetoed it, saying he would only go as far as other states. In 2016, the legislators yielded and Rauner enacted the legal limit of 5 ng of THC per mL of blood and 10 ng/mL of “other bodily substance,” which wasn’t defined in the law. For some attorneys and scientists the language implied saliva, but cannabis tests using it were still in their infancy.

At the State Police-run labs, forensic scientists determined that only blood testing would provide accurate results for DUI investigations under the new law. But at the UIC lab, Bash and Larsen took the law to mean urine testing was fair game.

Because of the vague statute, Bash told Injustice Watch, “the lab decided to provide the information objectively and allow the attorneys, judges, and courts to interpret the law as is appropriate.” To provide information on the amount of THC in urine, Bash used a testing method that converted metabolites back into the drug.

No other lab in the country offered to quantify THC in urine for Illinois prosecutions.

After cannabis was added to the DUI law, the lab’s invoicing for cannabis testing skyrocketed. University financial records show the lab billed just ten law enforcement clients for a total of $4,455 for cannabis testing in 2016. The following year the lab’s client list grew to seventy-one agencies with total billing of $37,650, most of which was done specifically for DUI investigations, records show.

“The demand grew rapidly and we developed a backlog,” Bash told Injustice Watch.

The lab was particularly popular in suburban collar counties. Law enforcement from Lake, McHenry, Kane, DuPage, and Will counties accounted for about one-third of its cannabis testing business in 2017. The following year it was more than half. This growth was driven in large part by DuPage County clients, in particular the Carol Stream Police Department, which has a reputation for aggressive DUI enforcement.

“We were more active in drug-impaired driving arrests perhaps than other agencies,” Carol Stream Police Department Deputy Chief Brian Cluever told Injustice Watch. Testing urine in DUI-cannabis cases “was important because it was less invasive than having to collect the blood,” he added. “With blood you have to have a certified phlebotomist to do that.”

Between 2022 and 2024, an average of about 22,000 Illinois drivers were arrested for DUI each year, according to data compiled by the Illinois Secretary of State. About a quarter of them were in Cook County, with DuPage County—which has less than one fifth of Cook’s population—coming in second. The state data doesn’t specify arrests by substance, but attorneys practicing DUI defense told Injustice Watch most cases stem from alcohol.

Still, the UIC lab analyzed hundreds of human samples for THC and its metabolites every year, mostly for DUI investigations. In total, it issued more than 2,200 reports on human blood and urine samples tested for cannabinoids between 2016 and 2024, according to statistics obtained by Injustice Watch. The university denied a request for the underlying lab reports, and Injustice Watch has filed a lawsuit against the university to obtain them.

While scientifically unfounded quantification of THC in urine continued at the UIC lab, at the end of March 2021, internal records show, the lab documented another problem—one the lab later acknowledged had compromised the integrity of its blood testing, too.

Scientists from a major forensic lab in Pennsylvania published an article in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology describing how their lab’s machines failed to tell the difference between two types of cannabis molecules.

The problem was highly technical, but in Illinois, this technicality could make the difference between freedom and years of imprisonment. The cannabis plant is composed of many chemical substances. As the fibers of the plant material are broken down into its molecules, there’s the stuff that gets people high—various types of THC—and the stuff that doesn’t, like cannabidiol, or CBD. Illinois law specifies DUI suspects must be tested for delta-9 THC. The Pennsylvania lab found its machines were not properly set up to see the difference between delta-9 and delta-8 THC—another psychoactive compound that is legal in many states, including Illinois. It meant when body fluids containing both types of THC, or just delta-8, were loaded into the machine for analysis, the machine would report its findings as delta-9.

A week after the publication of the article, Larsen got a call from one of the head toxicologists at the Illinois State Police, according to internal email records filed in court.

“Apparently some folks are having problems with the detection and separation of Delta-8 and Delta-9-THC,” Larsen wrote to Bash and two junior analysts. “Has this been an issue yet?” Bash, who by then had been promoted to an additional role as the lab’s quality manager, wrote back she would have one of the junior staffers check.

On March 31 the junior staffer ran the test, according to lab records filed in court. The lab’s machine showed it was not seeing the difference between the two types of THC. The email conversation among the lab personnel about the issue dropped off. After that, Bash told outsiders in emails the lab had no problem distinguishing the THC types while internally Bash and Larsen acknowledged they did.

Meanwhile, the State Police labs, which had discovered the same problem, were scrambling to fix their blood-testing methods.

On May 11, 2021, ISP’s toxicology technical leader Shannon George sent a letter to prosecutors and law enforcement agencies around the state describing the problem, promising to issue amended lab reports for all affected cases and to reanalyze blood samples using a corrected testing method where possible. Ultimately, ISP issued amended reports for 1,110 cases, according to a spokesperson.

The day after getting ISP’s letter, Kara Stefanson, a forensics liaison at the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, which mostly relies on ISP for toxicology, emailed Bash: “Does your testing allow for the separation of these two isomers of THC in blood?” Bash, copying Larsen on the email, wrote back that it did.

According to their own test of the lab’s machinery and internal emails, the assertion was not true.

For nearly three years, the UIC lab kept testing blood and urine in DUI cases using a method unable to properly detect the presence of delta-9 THC—even though the state’s legal limits are tied exclusively to delta-9.

Two years after the initial documentation of the problem, the lab’s main point of contact from the Carol Stream Police Department emailed Bash asking whether the lab had the capacity to test for delta-8 THC as the village was exploring ordinances to prohibit its sale. As Bash and Larsen considered in an email exchange how to respond, she reminded him “we couldn’t see the difference when it was mixed with delta-9.”

Larsen wrote back: “I do remember that.”

In her written response to Injustice Watch questions, Bash maintained the lab “could distinguish between the isomers and if delta-8 THC was present it would have been noticed.”

But in their internal investigation report, UIC’s lawyers wrote the March 2021 test “indicated that the methodology used could not adequately separate the isomers.” The lawyers added their team “found no evidence that [the lab] ever considered implementing changes, nor did it find evidence that [the lab] analysts understood the limitations of the methodologies used by the lab in quantitating Delta-9.”

While the problem with the UIC lab’s machines remained unreported to the public and testing of blood and urine continued, the DuPage County Public Defender’s Office, at McMahon’s urging, mounted a major challenge to Bash’s admissibility as an expert witness.

After years of handling an ebb and flow of cases tied to the lab, the office had ten clients at the same time charged with misdemeanor DUI-cannabis based on the lab’s urine testing—nine cases prosecuted by the village of Carol Stream, and one by the DuPage County State’s Attorney’s Office. McMahon convinced his superiors it was a good opportunity to ask a judge to bar Bash from testifying in all of them instead of fighting each individually.

In April 2023, his office flew in Virginia-based forensic toxicologist Marilyn Huestis, one of the world’s leading experts on the impact of THC on driving, whose research Bash has cited to justify her own work. Huestis was asked to testify in one hearing consolidating all ten cases. Before the judge even swore her in, the DuPage County State’s Attorney’s Office dropped its case.

The courtroom was packed with scientists from around the state, police chiefs, and attorneys who came to see the celebrity toxicologist. A few of the defendants were there, too. Bash didn’t attend, citing a COVID-19 infection.

Huestis, who took the stand in a flowing blue skirt and blouse set with large statement glasses and her gray curly hair cut short, used the only two free days she had that month to come to Wheaton and told Injustice Watch she accepted a lower payment than she normally charges to show up to court.

Huestis testified about extensive scientific evidence that “free THC”—the term scientists use to refer to the drug—does not show up in the urine of either occasional or frequent cannabis users. She testified the drug’s metabolites can be found in people’s urine up to twenty-four days after last use, making urine inappropriate for testing in DUI investigations. Contradicting Bash’s assertions, she testified that the field of toxicology does not treat free THC and its metabolites as the same thing. Huestis testified that in more than fifty years of working in toxicology with hundreds of colleagues she had never heard another toxicologist claim THC and its byproducts in urine are equivalent.

“What she did was wrong,” Huestis said emphatically in an interview with Injustice Watch. “Forensic science is all about truth. Everything we do—the DNA people, the gun casing people, all the forensic sciences—is about using scientific evidence to get at the truth. And if something is wrong scientifically, and then it’s used in a manner in which it affects the truth, then that could affect anyone.”

Ultimately the judge never ruled on Bash’s admissibility as an expert. The prosecutor for Carol Stream dropped its cases before Bash had an opportunity to return to court to defend herself. But Huestis’ testimony led the lab to pause quantifying THC in urine.

“With the reception of the testimony from Huestis,” Bash wrote in an email to Carol Stream police officials a few weeks after the hearing, “my lab director and I have temporarily suspended our urine quantifications for THC simply out of an abundance of caution.” In July 2023, after the cases were dropped, she emailed the Carol Stream police officials with an update: “lf people are comfortable with it, we could start quantifying the urine samples again,” Bash wrote, “but I would just put it out there that this issue is obviously going to come up again.”

Though word was spreading about the courtroom assault on Bash’s credibility as an expert witness, less than two weeks after the hearing with Huestis, Bash was back on the stand in Cook County. She was testifying in a case against Caleb Rallings, a former Forest Preserves employee who had been charged with aggravated DUI and reckless homicide after driving his work truck into a line of cars, causing the death of one person.

Doctors testified nineteen-year-old Rallings had experienced a dehydration-triggered delirium after spending several 90-degree days in a row doing hard physical labor and not drinking enough water. Bash reported finding THC metabolites in his urine but said the sample was too small to quantify how much. Her lab report notes that no THC was found in his blood. Still, she testified the presence of one of the metabolites in his urine suggested Rallings had consumed cannabis twelve to twenty-four hours before driving—an estimation about last use that toxicologists are trained not to make and that Huestis told Injustice Watch was “dead wrong.”

One of the defense witnesses, pharmacologist James O’Donnell, said he was stunned at Bash’s testimony as a fellow scientist.

“I describe it as chemical heresy,” O’Donnell said of Bash’s methods and testimony. “Mr. Rallings was lucky that he had a judge who saw through her testimony and accepted mine.”

Rallings was ultimately acquitted on the DUI charges but found guilty of reckless homicide.

Six months after the Rallings case, Bash testified in the case that would ultimately cause her the most serious damage. A college student from Cook County named Jonathan Franco had been charged with aggravated DUI and reckless homicide after crashing his car into an oncoming vehicle in Hanover Park.

Franco had just finished a graveyard shift at a FedEx package sorting facility and was on his way home when witnesses saw his car drift across the double yellow lines and collide head-on with a vehicle in which a man was driving with his twelve-year-old son. According to Hanover Park police reports, witnesses said they never saw Franco’s car swerve or try to avoid the collision. The father died.

Bash found the amount of THC in Franco’s blood was well below the legal limit. Yet during grand jury proceedings to indict Franco on aggravated DUI charges, a Hanover Park detective testified “she was able to scientifically confirm” Franco was “under the influence of cannabis at the time of the crash.” Once she reached the witness stand herself, Bash stood by this characterization.

Bash testified she had no opinion about whether Franco was impaired because “that’s not what toxicologists do,” but the presence of any THC in Franco’s blood meant that “scientifically, they were under the influence.”

Franco’s attorney sought to have the DUI charges dismissed, arguing Bash’s testimony misled lay people in whose minds “science is equated with truth, and here it was not.”

The state dropped the aggravated DUI counts against Franco and offered him a five-year plea deal for reckless homicide. He had already been on electronic monitoring for more than two years and spent fourteen days incarcerated. Still, media coverage of the case suggested Franco was a high driver who didn’t get a harsh enough sentence.

Two weeks after Bash’s testimony in Franco’s case, someone filed an anonymous complaint against Bash with ANAB, the national accrediting agency. The complaint alleged “untruthful, inaccurate, and unqualified testimony was provided by a toxicology analyst” at the UIC lab, according to records obtained from the university.

How exactly the accrediting agency investigated the complaint remains a secret. “In light of confidentiality restrictions we have with our clients we can’t release information,” Pamela Sale, vice president for forensics at ANAB, told Injustice Watch.

But shortly before ANAB auditors arrived for a scheduled inspection in February 2024, UIC officials told Bash they wouldn’t be renewing her contract, and shut down human testing at the lab. All contracts with law enforcement were abruptly terminated, and the agencies were asked to come retrieve their blood and urine samples.

The lab personnel were caught off guard by the closure. Bash wrote to a Carol Stream police sergeant on Jan. 10, 2024, that she and her colleagues “were shocked by the university’s decision and are working to navigate this on a personal level.” The next day, she submitted a resignation letter, effective at the end of the month.

The accrediting agency’s audit report detailed a slew of problems at the lab: months of missing records on “calibrators and controls used in THC quantitative testing”; years of missing evaluations on THC measurement uncertainty; no procedure to “preclude an individual from technically reviewing their own work”; no instructions for reporting inconclusive results; failure to properly review and document complaints about laboratory activities. The instrument used for THC screening hadn’t received required annual maintenance in nearly two years.

When an assistant state’s attorney from Kane County called Larsen to ask why the lab was closing, “I let him know it was because we were not profitable. Nothing related to the quality of our work,” Larsen wrote in an internal lab memo.

No one in a position of administrative or financial authority over Larsen and his lab at UIC or the University of Illinois system agreed to be interviewed for this story—not Pharmaceutical Sciences Department Chair Nancy Freitag, not the College of Pharmacy Dean Glen Schumock, not Vice Chancellor for Health Affairs Robert Barish, nor UIC Chancellor Marie Lynn Miranda. University of Illinois system President Timothy Killeen and Board of Trustees Chair Jesse Ruiz also refused to answer questions.

In their internal investigative report, the university’s lawyers wrote the decision to stop human testing at the lab “was the culmination of a process, which began in 2022, that weighed the financial burden of [the lab’s] human testing along with the decision to suspend the forensic science programs at the College.” According to the report, the lab wasn’t generating enough revenue to cover the expense of human testing.

Despite the growth of the lab’s law enforcement client list, less than 5% of its reported revenue came from human testing between 2017 and 2024, according to financial records reviewed by Injustice Watch. Instead, most of the lab’s money still came from testing racehorses, which primarily came from the Illinois Racing Board, but also included clients in Maine, Oregon, and Texas.

Weeks after the lab ceased human testing, the accrediting agency informed Larsen about the results of its investigation into Bash. The agency “determined that the allegations related to inaccurate and unqualified testimony have merit,” Sale wrote in an email to Larsen, while finding the allegation that she was “untruthful” to be without merit.

Attorneys in DuPage County soon caught wind of these findings against Bash. In April 2024, prosecutors issued the first disclosures about Bash’s history of giving “inaccurate and unqualified testimony.” She was now a radioactive witness.

The disclosures reverberated among attorneys and forensic scientists throughout the state. Email records obtained by Injustice Watch show Illinois Traffic Safety Resource Prosecutor Jennifer Cifaldi, also an employee of the University of Illinois, fielding questions from prosecutors who had relied on Bash for testimony.

At the same time, the lab’s remaining staff began to receive questions from defense attorneys and prosecutors about the lab’s ability to distinguish between delta-8 and delta-9 THC. One of the analysts on the racehorse testing side of the lab repeated the test that was first run in March 2021. “In short, we are unable to distinguish between the two isomers using the current methods,” the analyst wrote in an internal lab memo. “It is unknown how many cases this may have affected.”

The analyst and Larsen emailed back and forth about whether it made sense to figure out how many cases were affected and how to move forward. On May 16, 2024, Larsen finally acknowledged that the analytical method used by the lab “may not” have been able to tell the difference between delta-8 and delta-9 THC in human samples going back at least six years. In a letter to state’s attorney’s offices in seventeen counties, Larsen wrote “this issue has been of concern since we learned of its existence.”

Larsen also sent a passionate three-page letter to ANAB asking the accreditation agency to reconsider its negative findings against Bash. Larsen wrote he did not see any problems with her testimony in Franco’s case, where she had described him as “scientifically under the influence” even though he was well below the legal limit for THC.

Larsen argued Bash had no meaningful opportunity to defend herself against the accusation she testified improperly. He called the disclosures issued by prosecutors based on ANAB’s findings “misleading and potentially defamatory,” and added the agency’s reputation was on the line.

“It is appalling how rapidly an accomplished and honest professional’s career can be jeopardized by misinformation and accusations shrouded in secrecy,” he wrote.

Larsen never got a response. As the academic year came to a close, Larsen retired, though he continued fielding panicked communications from the lab’s former clients trying to figure out their exposure. He now works as an adjunct lecturer in forensic science at Loyola University Chicago.

Bash, meanwhile, founded her own science consultancy, remains a member of the Illinois Impaired Driving Task Force, and continues to be certified by the American Board of Forensic Toxicology. She remains able to testify in Illinois courtrooms.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, false or misleading forensic evidence helped convict a quarter of the more than 4,000 people wrongfully convicted in the United States since tracking began—including seventy-nine from Illinois.

Scandals involving junk science in the criminal legal system tend to involve whole forensic disciplines such as controversial bite mark and bloodstain-pattern analysis, which are admissible because of rules on expert testimony set by the U.S. Supreme Court.

It can be difficult to challenge junk scientists because the only people allowed to weigh in about their legitimacy are other scientists in the same field. Bite mark analysts must be impeached by other bite mark analysts, not by dentists or osteologists. Once admitted into a case, junk science becomes harder to challenge in others, especially when court decisions relying on it are affirmed on appeal.

Forensic toxicology, however, is not considered a junk science. Where bloodstain-pattern analysis is akin to palm reading, forensic toxicology is more like measuring someone’s hand. Its practice is subject to standards governing toxicology beyond the legal system. To be taken seriously, a lab seeking to sell its testing services must be accredited by an independent body such as ANAB, which audits thousands of workplaces globally, from steel mills in Angola to animal health monitoring facilities in Ireland. UIC’s lab was one of nearly 200 sites ANAB accredited for forensic toxicology in the United States.

Yet an accrediting agency is not a watchdog. Labs undergo accreditation voluntarily, and audits by accrediting bodies often come down to verifying that the lab has written down its operating procedures and is following them.

“We do expect that our laboratories are operating in good faith,” said ANAB vice president Sale. “It’s hard to detect if somebody wants to hide something from you. We’re only there for a short period of time.”

ANAB does not review how lab analysts testify or check the validity of scientific principles labs use as the foundations of their testing approaches.

“Accreditation is a baseline requirement for quality management of any forensic science service provider,” said Sarah Chu, director of policy and reform at the Perlmutter Center for Legal Justice at Cardozo Law School in New York. But to achieve true oversight of forensic science, she said, states need “commissions that have the power to investigate and are transparent and have the trust of all the stakeholders in the system.”

The gold standard for forensic science oversight in the United States has evolved in Texas over the last twenty years, after high-profile lab scandals there exposed numerous wrongful convictions. The Texas Forensic Science Commission, formed in the wake of those scandals, today has its own accreditation requirements for crime labs and analysts; when labs and individual scientists lose the accreditation due to misconduct or incompetence, the evidence they produce cannot be used in Texas courtrooms. The commission publishes reports naming rogue scientists and detailing misconduct at labs; though the reports themselves are not admissible in court, they add public accountability.

In addition, Texas has a state law requiring prosecutors to continuously disclose evidence to defendants; prosecutors can be disciplined for failing to do so. There’s a “junk science writ” that allows people to seek new trials if they can show flaws in the forensic evidence used to convict them. Most recently, the state created a portal making crime lab files directly open to both prosecutors and defense attorneys, eliminating some of the burdens of transmitting evidence.

Experts who have studied forensic oversight in Texas told Injustice Watch its broken system didn’t change overnight. But once the state committed to principles of transparency and accountability, the culture of crime labs, law enforcement agencies, and the courts began to shift. Chu, who wrote her doctoral dissertation about the Texas Forensic Science Commission, found over a period of four years external complaints about labs fell precipitously as labs’ self-reporting of issues to the commission climbed.

Balancing disclosure of lab mistakes with concerns about being sued is “always uncomfortable,” said Peter Stout, director of the Houston Forensic Science Center, one of the largest crime labs in the country. “But the rights of the victims and defendants supersede the fear of the agency.”

Recent lab scandals in other states have laid bare the inadequacy of forensic science regulation nationwide. In Massachusetts, a state crime lab chemist was convicted on obstruction of justice charges for falsifying lab results in as many as 34,000 cases while another served an eighteen-month prison sentence for using the drugs she was supposed to be testing in some 24,000 cases. In Washington state, years of blood drug tests were suppressed due to methamphetamine contamination at the state toxicology lab. In Colorado, a former forensic scientist is facing 102 felony counts for alleged manipulation of DNA evidence. All the reforms in Texas notwithstanding, bad forensic science still finds its way into courtrooms there.

Stout compared the lax supervision of crime labs to the much stricter oversight for labs that do workplace drug testing for federal agencies, regulated through the National Laboratory Certification Program. If a lab the size of his was subject to as much scrutiny as a one doing basic urine drug testing for, say, postal workers, “I would have an audit team on the ground here in the laboratory four times a year” instead of once every four years, Stout said. He added the funding for forensics lab work across the country is also drastically lower than for workplace drug testing labs.

“The reality is, in this country, Texas is abnormal,” he said. When it comes to forensic science, “there basically just isn’t any oversight.”

In researching an upcoming book, Stout found only eight states with laws requiring forensics labs to be accredited or certified to produce evidence used in criminal prosecutions. In this environment, bad science can flourish because most defendants, police officers, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges do not have the expertise to evaluate the validity of what scientists say.

In Illinois, the law is silent on accreditation but labs and individual analysts must be certified by the Illinois State Police to perform forensic testing. This process involves periodic submission of proof that lab analysts are passing proficiency tests. Like accreditation, certification adds a gloss of legitimacy without serving a watchdog function.

Despite periodic crime lab scandals—systemic failures in the Chicago Police Department’s fingerprint analysis reported in 2017; lack of scientific method validation in State Police blood alcohol testing reported in 2015; a local DNA analyst who failed to disclose evidence of innocence for years starting in the 1990s—Illinois, like most states, has no government body in charge of oversight and auditing of forensic sciences.

Following the discovery of a 766-case DNA testing backlog for Chicago murder cases, Gov. JB Pritzker signed a law in 2021 creating the state’s first Forensic Science Commission. It was tasked with ensuring “the efficient delivery of forensic services and the sound practice of forensic science,” but it has no authority to investigate complaints, shut down labs, discipline analysts, or issue legally binding findings.

Instead, the commission is an advisory body housed inside the Illinois State Police, which pushed for its creation in the first place. The chair of the commission is State Police Director Brendan Kelly—who also oversees most of the state’s forensics labs. Kelly declined Injustice Watch’s request for an interview.

Donald Ramsell, an attorney specializing in DUI defense who has long crusaded for more forensic science accountability in Illinois, said crime lab oversight throughout the state is “subpar and not trustworthy.”

With no one in charge of surveilling the underlying scientific validity of lab methods, “when you have a rogue lab or a lab operating in non-conformance with accepted scientific practice, if they don’t self-report most of it goes undiscovered,” Ramsell said.

He said Illinois’ Forensic Science Commission falls far short of the authority its name implies. “Instead of improving the practice of forensic science in Illinois, it’s become another layer of paperwork,” Ramsell said.

The commission meets its first true test in the UIC lab scandal. Its handling of the matter thus far shows the lengths left to go before it can provide a meaningful backstop to junk science in the courtroom or serve as a forum for correcting forensic injustices.

The Illinois Forensic Science Commission, which has received virtually no media coverage since it began meeting in 2022, has fourteen members, including crime lab directors and criminal legal systems stakeholders. Members are divided into subcommittees focused on public policy, DNA, training, and quality issues at labs.

In February 2024, right as the UIC lab was shutting down human testing, the commission’s public policy subcommittee heard presentations from two forensic scientists about the lack of scientific basis for testing urine in DUI-cannabis investigations. One also spoke about misleading testimony coming from the lab and the imperative to clarify the state’s DUI law on urine testing in order to prevent wrongful convictions.

“I can’t remember how many times we’ve discussed this issue, so it shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone,” said Claire Dragovich, one of the commission members and the director of the DuPage County Forensic Science Center. She wanted the commission to recommend a change to the DUI law. “I’m sure [Illinois State Police] legal will have opinions about how much we can say in a letter to support this, but I want to get crackalackin’,” Dragovich said.

The commission made no public comment about the UIC lab, but seven months later it issued a recommendation to amend the DUI law to specify the measurement of “free” delta-9 THC only, which would put an end to urine testing.

State Sen. Julie Morrison introduced a bill explicitly excluding urine from DUI-cannabis testing in February 2025, but it died in committee with no co-sponsors or hearings. Morrison declined Injustice Watch’s multiple requests to discuss the bill.

This year, for the first time, the commission asked the UIC lab to submit a report about its “significant non-conformities”—lab-speak for major problems that require documented correction.

The UIC lab sent a report detailing just two problems for 2024: the failure to separate delta-8 and delta-9 THC and the issue of Bash’s inaccurate and misleading testimony about a defendant being “scientifically under the influence.”

Members of the commission’s subcommittee dedicated to lab quality met over Webex to discuss the UIC lab’s response in April. Most had their cameras off. The discussion sounded more like a monologue by Dragovich, the subcommittee chair who was the only person to express serious concern about the UIC lab at any commission meetings.

Dragovich said it was strange the lab had not issued any amended lab reports after discovering it could not tell the difference between two types of THC. She spoke for a while about it being impossible to testify about the meaning of past lab results without amended reports.

Dragovich paused, making room for any of the other subcommittee members to comment. She waited for thirteen seconds, then broke the awkward silence herself: “If no one has any comments about that, we can just move on to the next issue they reported.”

She read out the lab’s explanation of the problems with Bash’s testimony and said it didn’t make sense the lab hadn’t tried to figure out how many cases were impacted by statements like “scientifically under the influence” to refer to people who weren’t high while driving.

She added she couldn’t understand why the lab hadn’t notified all prosecutors’ offices about Bash’s past improper testimony. “I don’t understand why it was acceptable to not notify,” she said, “like it’s a really serious issue.”

Dragovich concluded the lab’s personnel can be subpoenaed years after they left its employment. “So even though the lab is not currently performing any casework, it is possible that the results from this laboratory are still being used in prosecutions and that past employees are still testifying, and there is zero oversight on what’s happening during that process.”

In June, the full commission approved its annual report about problems at state crime labs. It noted labs should issue amended reports anytime they discover testing has been inaccurate, and when a lab discovers inaccurate testimony by an analyst it should identify all impacted cases and notify prosecutors. The commission’s advice—which has no legal bearing—did not include any mention of labs’ duties toward the people whose body fluids they test.

Chu, who reviewed the commission’s report, told Injustice Watch it isn’t sufficient for crime labs that discover problems to notify only their law enforcement clients. She likened the failure to notify defendants themselves to a hospital failing to notify a patient of a diagnostic error.

“Forensic labs and justice system actors should have a duty to notify individuals when flawed forensic evidence may have contributed to their conviction,” Chu said. “A prosecutor might decide it wouldn’t have changed the case outcome,” but in the legal context “determining the value of evidence is the role of the courts, not one party.”

With the Forensic Science Commission lacking authority to force any disclosures, discipline scientists or challenge labs’ accreditations, the University of Illinois remains the only institution that can make amends for what happened at the UIC lab.

Defense attorneys who knew about UIC’s internal investigation of the lab were eager to read their findings. The report, however, came as a disappointment.

McMahon called it “biased and incomplete. In my opinion it’s to protect the university from lawsuits.” Ramsell called it “a whitewash.”

According to the report—which does not address the problems with testing urine in DUI-cannabis investigations—the lab’s leadership merely “missed the significance” of the delta-8 and 9 separation issue. UIC’s attorneys also undercut the lab’s own admissions about its flawed testing method, describing them as “overbroad and inaccurate.”

The lawyers wrote they consulted with Pennsylvania-based forensic toxicologist Michael Coyer to review the lab’s methods and concluded they were “at all times appropriate and met accepted scientific standards.”

Asked by Injustice Watch whether he was aware of the lab’s protocols for testing urine, Coyer said he had “no knowledge” about that. “I just looked at the technical stuff,” he said in a brief phone conversation. “I only ever talked to the lawyers.”

Bash, who at one point retained famed criminal defense attorney Jennifer Bonjean—known for representing wrongfully convicted Chicagoans as well as high-profile clients including Harvey Weinstein and R. Kelly—“declined numerous attempts from the investigative team to be interviewed,” according to the report. Nevertheless, the university declared “there is no evidence to support the allegation that Ms. Bash knowingly provided false or inaccurate testimony in any criminal proceeding.”

Dwan Thompson, who now works as a CTA bus driver, was exonerated at the end of January along with seventeen other people who had been convicted of cannabis DUIs in DuPage County based on the UIC lab’s urine analysis. DuPage County State’s Attorney Bob Berlin declined Injustice Watch’s request to discuss the decision to clear the cases. McMahon and his colleagues at the DuPage County Public Defender’s Office have been uniquely aggressive in pursuing justice for people convicted with evidence produced by the lab.

Besides McMahon, two private defense attorneys—Ramsell and Paul Moreschi, who represented Jonathan Franco—have led the charge fighting the UIC lab’s evidence in pending DUI cases as well as trying to get convictions overturned. They are currently representing Corey Lee, who is serving a six-year prison sentence for aggravated DUI. Lee showed no signs of impairment after an early-morning car crash that killed a father and son in Boone County. But Bash found 6.5 ng/mL of THC in his blood, over the legal limit. Lee, who later admitted to being a frequent recreational user, told police he stayed up all night with his sick dogs before heading out for work. He said he fell asleep at the wheel and ran a stop sign and that he had last smoked twenty-seven hours before the accident. The judge found him not guilty of reckless homicide and operating a vehicle while fatigued. If not for Bash’s lab report, Lee would be a free man.

“I know that I was not under the influence that morning,” Lee told ABC7, which first reported on his case and problems at the lab in December. “As far as the UIC lab, I believe that somebody there should have to answer for this.”

In a statement recently filed in Lee’s case, the UIC lab’s director of operations told Moreschi one of the machines used to analyze Lee’s blood showed signs of THC contamination before his sample was run. In a statement to Injustice Watch, Bash denied the machine was contaminated.

Another man whose incarceration is tied to Bash’s lab work and testimony is William Bishop, a forty-seven-year-old Chicagoan serving a thirty-one-year prison sentence.

In May 2020 Bishop, a successful former triathlete with a flourishing personal training business, was in the middle of a psychotic episode when he decided to drive from his home in River North to see his parents in Lake Barrington, according to court records, including multiple psychiatrists’ testimony. Bishop described his hallucinations to Injustice Watch and said they worsened in the car as he sped down a two-lane road in rural McHenry County. He said at the time he was convinced he was being chased by a mob and thought he heard Howard Stern on the radio telling him to drive into the next car he saw. Convinced he would die if he didn’t obey, Bishop said, he slammed his Jeep into a large cargo van going 84 miles per hour. The driver of the van died, and the passenger survived with life-altering injuries.

Bishop was eventually diagnosed with Bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. He spent weeks in an inpatient psychiatric unit after the deadly crash. When he was discharged he was taken to the McHenry County Jail and charged with eleven counts, including murder and aggravated DUI. State’s Attorney Patrick Kenneally’s entire theory of the case was that marijuana made Bishop do it.

In a recent interview, Bishop told Injustice Watch he used marijuana to “self-medicate” before he had the right diagnosis and treatment for his mental illness. He maintained he last took a hit from his vape pen hours before driving on the day of his accident. But Bash’s lab report showed at least 9.6 nanograms of THC in his blood, nearly twice the legal limit.

Bishop told Injustice Watch he was sure he wasn’t impaired by marijuana while driving. He never even saw his lab report but said his lawyers told him he was over the legal limit. “We really didn’t address the cannabis subject much after that,” he said. “We all agreed I would be found guilty of DUI and should hope for a light sentence on that charge.”

In a weeklong trial focused mostly on expert testimony from doctors about his mental state, Bash’s testimony about the marijuana in his body seemed almost irrelevant. Bishop was going for an insanity defense.

The judge found Bishop guilty but mentally ill and imposed a twenty-four-year sentence for the murder and a consecutive seven years for the aggravated DUI. Kenneally went on to hold up Bishop’s case as a prime example of cannabis-induced psychosis.

Bishop lost his appeal. He and his family said they were unaware of all the allegations against the lab until Injustice Watch reached out with questions.

“Now that we are learning about the lab’s unethical performance, I question a few things,” Bishop wrote to Injustice Watch over a prison text-messaging app. “1. Was there even any delta 9 THC in my system? 2. What were my real levels and were they even over the driving statute? 3. If there was Delta 9 THC in my system, how do we know it wasn’t from contaminated equipment and not a previous sample tested?”

Lee and Bishop are the extreme cases. Prison time for DUIs is rare, unless someone has multiple prior DUI convictions or someone dies in a crash. Most DUIs end up in misdemeanor court, where defendants usually plead guilty and accept punishment in the form of fines, probation, costly substance abuse counseling, and classes on the harms of impaired driving. These punishments can still be burdensome, especially for people in challenging life circumstances or in jobs dependent on clean driving records. DUI convictions cannot be expunged in Illinois.

Bishop and Lee were among some 680 people incarcerated in Illinois prisons for DUI offenses as of the end of March. How many of them were convicted with the help of lab work from UIC’s Analytical Forensic Testing Laboratory and testimony from Jennifer Bash remains unknown.

Northwestern University journalism residents Mitra Nourbakhsh, Kristen Axtman, and Sara Stanisavic contributed to this report.