South Side Venezuelan families are navigating a complicated mix of hope, uncertainty, and fear following Nicolás Maduro’s capture in Caracas and arraignment in New York. Questions about asylum, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), and the safety of loved ones back home have grown more urgent as these residents try to understand what shifting U.S. policy could mean for their lives in Chicago.

Marina Suares fled violence and political persecution in Venezuela with her children and grandchildren and survived a perilous trek through the Darién Gap and Central America before reaching the United States in 2023. She and her family were among the thousands of new arrivals who initially spent time sleeping on the floors of police stations in Chicago. Suares slept at the 2nd District station for nearly two weeks while seeking asylum and support after arriving with nothing.

When a fire destroyed the South Side apartment they had just moved into after leaving the police station, she and her family relocated temporarily to Washington, D.C. She still returns to Chicago regularly for immigration court hearings and to meet with the nonprofit supporting her asylum case. The Weekly checked in with her again after first speaking with her last year.

“I have this great feeling…that finally we are seeing a light,” she said about Maduro’s capture. “For us, this is a lot,” she said.

For her, Maduro’s capture represents the first consequences a top official has faced for the harm his regime has inflicted on ordinary Venezuelans. “At least we are seeing that one of them is paying for some of what so many Venezuelans have suffered,” she said. “But we know that the president here is doing that for something of his benefit,” she added.

While Suares expressed relief, and a sense of long-delayed justice, she said it doesn’t signal safety for her or her family.

Her relatives who remain in Venezuela live under constant fear and surveillance, particularly in Caracas and in her hometown of Maracay, she said. Family members have warned her not to send news or political content because police and armed colectivos—pro-Maduro paramilitary groups—routinely check phones. “There, you have to keep a low profile,” she said. “If there’s anything against the government, they beat you up, they arrest you.”

Although Suares made it out of Venezuela, she still finds herself constrained here. While she has a work permit, she avoids working outside the home out of fear of encounters with federal agents, who have used deadly force during traffic stops and immigration raids—most notably in the killings of Silverio Villegas González, an immigrant living in Franklin Park, Illinois, and Renee Nicole Good, a U.S. citizen in Minnesota, as well as arrests, detentions, raids, and deportations.

About having a work permit, her husband told her, “It doesn’t guarantee anything.” And Suares added that a nephew in Texas was detained and deported despite having one. He is now back in Venezuela, where she described extortion by police, violent crackdowns, disappearances, and a recent incident in which a child was killed during unrest in her hometown.

And since Maduro’s capture, she said conditions in the country have worsened. “Right now, it’s worse,” she said. “They are more oppressive, there is more abuse, more people are getting jailed.”

At a panel hosted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs last week, Francisco Rodríguez, a Venezuelan economist and professor at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies who previously served as an economic advisor to the Venezuelan government, emphasized that while Maduro is out of power, the Chavismo regime remains intact. “Trump cares about oil,” Rodríguez added. “He cares about U.S. economic interests.”

Rodríguez noted that the Trump administration also prioritizes messaging. References to drugs and crime, he explained, appear largely symbolic; Venezuela does not produce fentanyl, and most cocaine consumed in the United States comes from other countries. He also suggested that Maduro’s capture may have involved cooperation from insiders within Venezuela’s security and political structures, not opposition activists, but “figures who calculated that removing Maduro personally could preserve the broader regime.” Evidence to support that allegation has not yet surfaced.

In a statement last week, Mayor Brandon Johnson criticized the Trump administration’s military action in Venezuela, saying it “violates international law and dangerously escalates the possibility of full‑scale war.” He added that the “illegal actions by the Trump administration have nothing to do with defending the Venezuelan people; they are solely about oil and power.”

A mayoral spokesperson also said Johnson renewed his call for TPS, which is a temporary designation that allows certain Venezuelans to live and work in the U.S. due to instability in their home country, and access to asylum for migrants “in response to the instability and unsafe conditions created by President Trump’s reckless and illegal military action in Venezuela.”

Regarding TPS, the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC) noted that Venezuelan nationals living in the United States are currently not eligible. In a statement, the organization said: “Although Congress created TPS to provide relief for people whose countries face political and humanitarian crises, the Trump administration has already ended TPS for Venezuelan nationals.”

Courts have challenged the termination of TPS, but the Supreme Court allowed the government to keep it terminated while the case is under review. NIJC said this shows the administration is serious about revoking TPS and is unlikely to change course.

Suares’ case has followed a different legal path. She is seeking asylum, a protection based on individual claims of persecution rather than a broad humanitarian designation. In a statement, the NIJC said that people in the U.S. can still apply for asylum if they fear being hurt in Venezuela, even if they’ve been here for years. The government has tried to block asylum in some cases, but federal law still gives people the right to protection.

The U.S. used to have a parole program that let people from Venezuela and some other countries come to the U.S. safely with permission to live and work for up to two years. That program was ended by the Department of Homeland Security in March 2025, so there is no special pathway right now for Venezuelans or their relatives to come through parole.

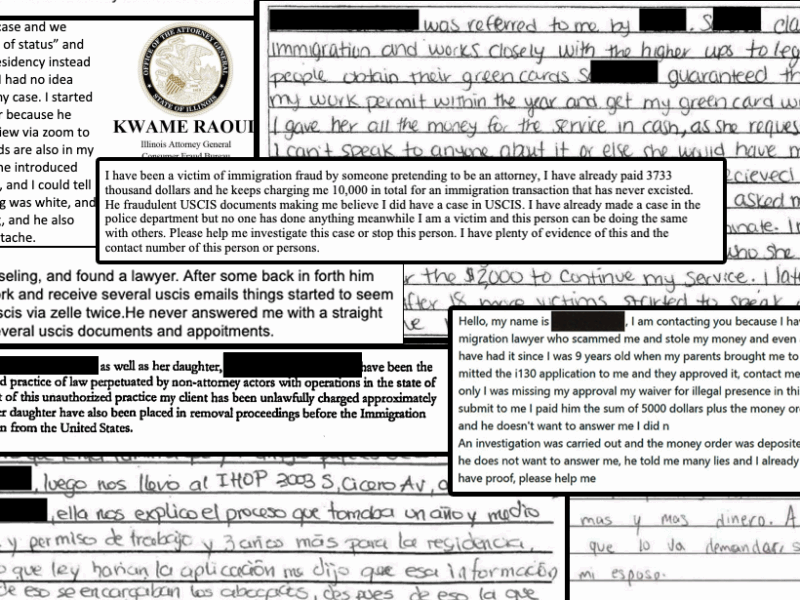

NIJC recommends anyone with questions about how their family members might be able to come to the U.S. should talk to a qualified immigration lawyer and to look out for scammers or fraudsters, as they “often prey on vulnerable immigrants at times of crisis.”

Luciano Pedota, the president of the Illinois Venezuela Alliance, said that while some have expressed hope they might return, “They find themselves in a bind going back to Venezuela…they have such a control system, they model Chavismo in which, in every neighborhood, every little town and every neighborhood, there is a snitch…an informant. And so many people have to leave their town, because if you don’t obey the ideology of the rule, they will ask you to do so then they will start harassing you.”

At the same time, many remain anxious about navigating U.S. bureaucracy. With temporary protected status ended and work permits offering limited security, “If there is not a pathway to have a legal status and to permanent residency, they will be extremely concerned,” Pedota said, highlighting the irony that, although they fled dictatorship, many Venezuelans are now caught in a legal limbo with fragile protections.

Trapped between a homeland marked by violence and oppression and a new country where security is fragile, the Suares family’s struggle underscores the broader reality for Venezuelans at home and abroad: freedom is not fully within reach, and the future remains uncertain.

“With everything that’s happening…I don’t go out,” Suares said. “Only to the grocery store or to church on Sundays. I don’t think this is a life.”

Alma Campos is the Weekly’s immigration reporter and project editor.

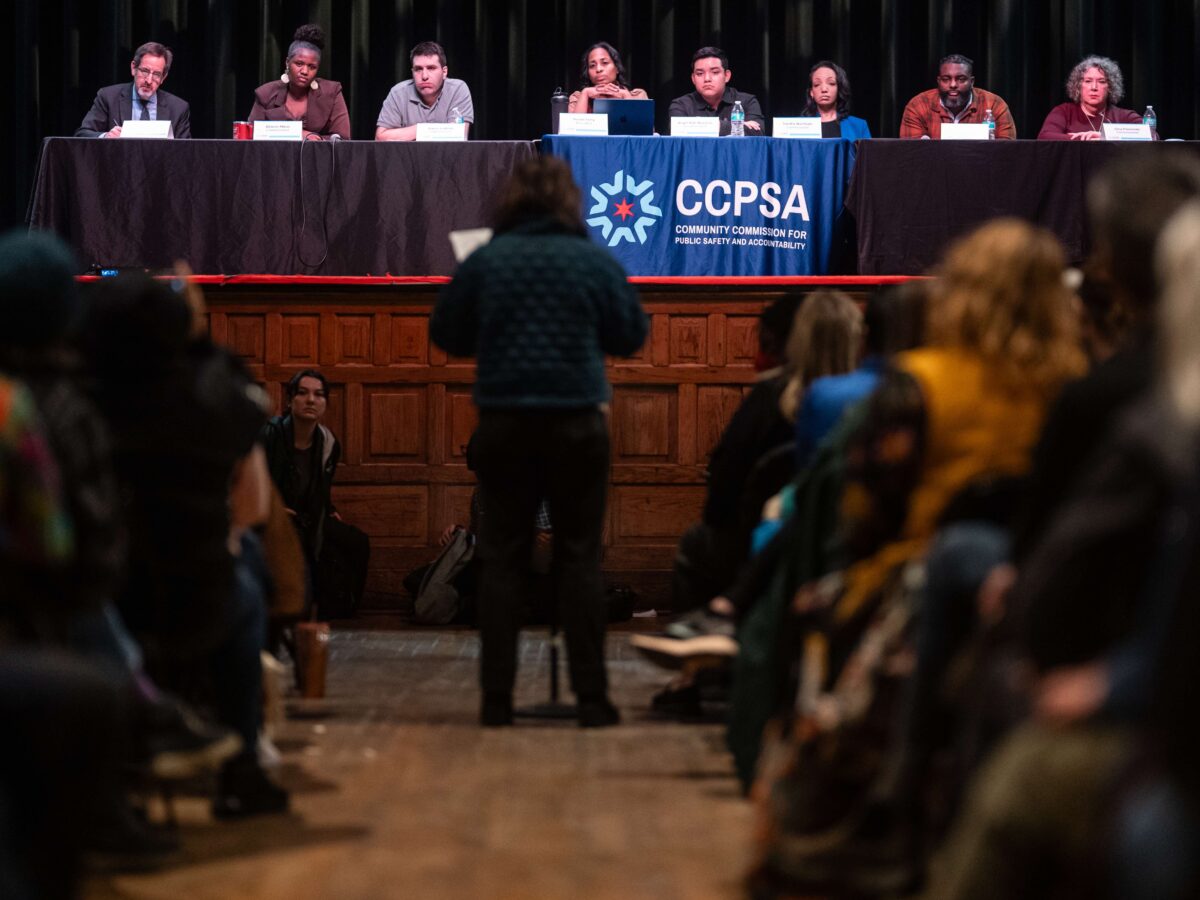

Residents Demand Oversight Commission Investigate CPD Cooperation with ICE

At a raucous meeting in Pilsen, hundreds of residents chanted “Who do you protect? Who do you serve?”

In Immigration Protest Cases, Feds Keep Striking Out

The Justice Department has aggressively prosecuted those who protest its mass deportation campaigns, but many of those prosecutions have fallen apart.

Fraudsters Target Immigrants Seeking Legal Help

In Illinois, immigrants have lost thousands of dollars to notarios offering legal assistance they’re not qualified to provide—as well as other impostors. Nationally, the figure is at least $1.2 million.