We will spend whatever it takes. Whatever that cost is, we will pay it.”

Those were the words of Chicago Public Schools CEO Forrest Claypool at a community event in June, just as CPS began testing its more than 6,000 sinks and faucets for lead-contaminated water.

Anna Espinosa, 38, was in the audience that night. School officials had planned for a crowd at the Back of the Yards high school gym, fully expanding the orange bleachers toward the middle of the basketball court where a table was reserved for CPS, Department of Water Management, and Department of Public Health officials. But only a handful of parents, teachers, experts, and reporters showed up, so the attendees were relocated to a dozen chairs around the table.

Claypool was soon peppered with questions.

”Why weren’t the meetings publicized widely?” one attendee asked.

“They were,” Claypool replied.

“Why did you wait to test until the media started investigating?” another asked.

“CPS launched this program, not the press,” Claypool said, bristling slightly at the insinuation.

And the exposure risks for CPS students from school fixtures? “Basically non-detectable,” Claypool assured those gathered on the court.

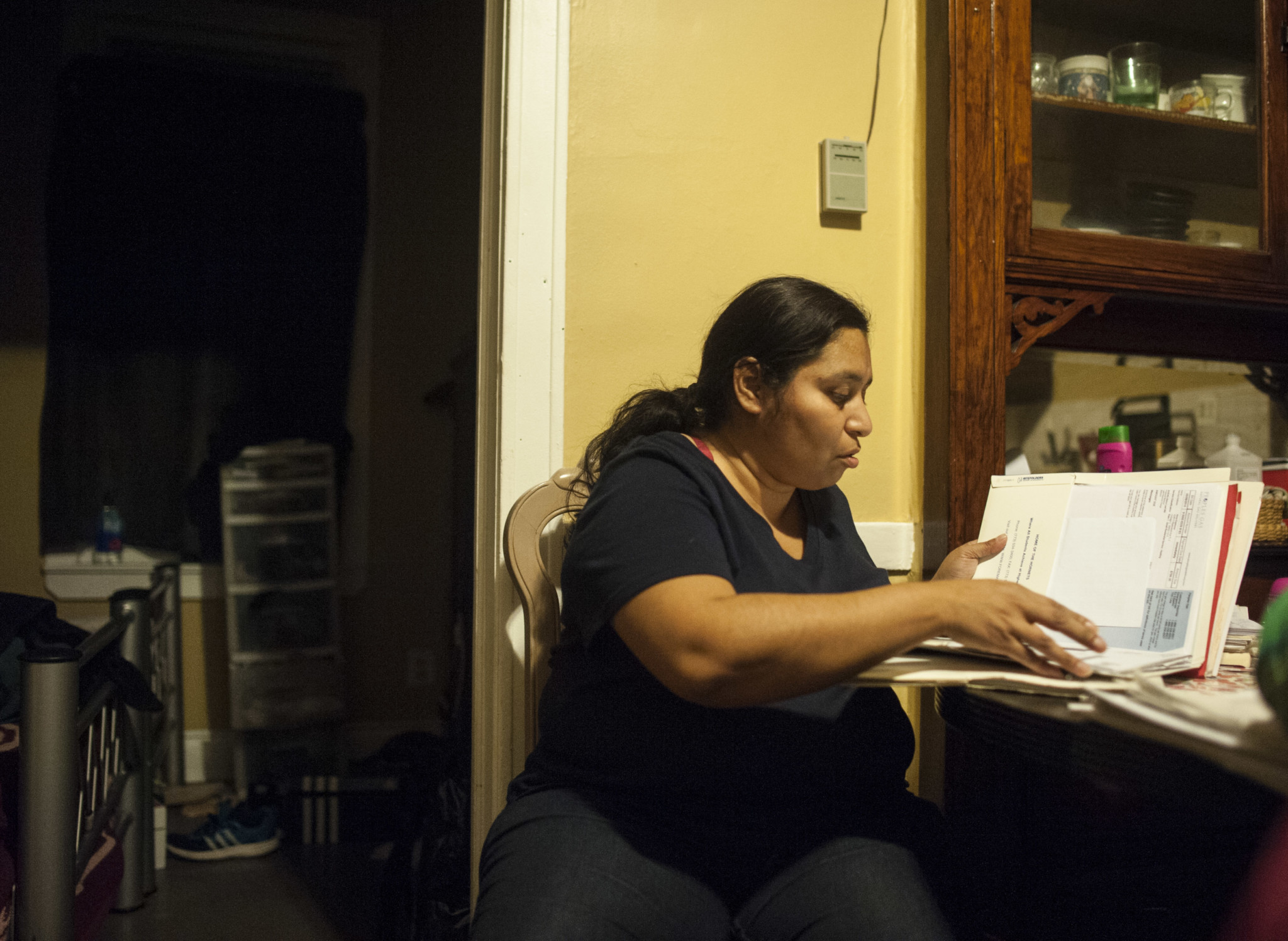

But the newly launched water testing was only one reason Espinosa attended the meeting that day. At the age of four, her autistic seventeen-year-old son had already been poisoned by lead in the family’s last home, she said, later telling reporters that the CPS officials she had just listened to were “full of it.”

Instead, Espinosa wanted to know what CPS would do for her son in his last years at Thomas Kelly High School. In other words, how does Chicago’s public school system plan to help students who were poisoned by lead as children and are now suffering the effects as young adults?

While CPS works to find and eliminate lead-contaminated fixtures in its buildings, students who arrive at school already exposed to lead still have limited options for treatment. Though the city imposes mandatory lead screenings on children before they turn six years old, a review of departmental policy shows that CPS has no official or comprehensive policy on how to assess and assist lead-affected children. Considering the symptoms and their effects—ranging from low grades to violent behavior—and compounded by budget cuts, the public health crisis of lead poisoning extends beyond today’s water fountains. What schools do and do not provide to children affected by lead will shape the futures of thousands of young Chicagoans.

An Invisible Legacy

The symptoms of lead poisoning include a range of seemingly unrelated ailments like abdominal pain, constipation, sleep problems, headaches, loss of appetite, and memory loss. Many are relatively mild and can be individually overlooked, but, in the case of lead poisoning, could pave the way for a myriad of lifelong effects including irreversible brain damage, aggressive behavior, lowered IQ, growth delays, and poor grades. Recent reports even link childhood lead exposure with trends in violent crime.

“Those [effects] happen even at low levels of lead poisoning. So these kids get poisoned before [age] 5, and they get to school already with learning disabilities,” says Howard Ehrman, an environmental advocate, University of Illinois at Chicago professor and former top official at the Chicago Department of Public Health. “One of the problems we have, not only with lead poisoning but all possible learning disabilities, is the fact that CPS and most public schools have never funded or made it a priority for enough people to do proper testing and then put the children, based on the Americans with Disabilities Act, into the right programs to treat their learning disability.”

Symptoms of lead poisoning often do not become apparent until a child has difficulty in school. And while those effects are often translated as bad behavior and underperformance, in a time of citywide cuts and changes to school budgets, which critics say could shrink special education funds, the impact of untreated lead poisoning raises tough questions for communities already facing disastrous levels of unemployment, incarceration, and public school closures.

In 1999, Fuller Park was the community area with the highest incidence of elevated blood lead levels among children tested, with nearly two in five kids testing positive. By 2013, only 2.8 percent of kids tested there had elevated levels. The dramatic decrease can be tied to a number of factors including disuse of leaded gasoline, an increase in lead screenings, and cleanup of lead paint in homes. But lead is an “absolute neurotoxin,” according to Ehrman, meaning that babies affected in 1999—now high school students—are likely impacted by the exposure even today.

Among those students is Espinosa’s seventeen-year-old son, Moises, who was tested in 2005 and had a lead count of 4.9 micrograms per deciliter, Espinosa says, adding that she believes it was higher in the years before. She says he was likely exposed to lead-based paint in their home, which is how most children accidentally consume lead. But small amounts of lead can accumulate in the body from many different sources.

The family’s Back of the Yards neighborhood, where the CPS community meeting took place in June, is part of the New City community area. In 2013, 1.4 percent of children (ages zero to six) tested in New City had elevated blood lead levels, putting the neighborhood fifteenth among Chicago’s seventy-seven community areas. Espinosa’s son attended schools in McKinley Park, Brighton Park, and Pilsen during that same time frame, some of which had sinks or water fountains with lead-contaminated water during this year’s tests.

“I couldn’t believe there was lead in my school [Perez Elementary], where I had grown up, and that there was lead in Pilsen Academy where [my children] went also,” she says.

Moises was diagnosed with autism at fifteen years old, and though scientists have not found a causal link between the toxin and autism, childhood lead poisoning has many of the same symptoms as Autistic Spectrum Disorder—and it has been found to contribute to autism severity in lead-poisoned children.

Espinosa’s message for parents today: “Keep insisting on getting the resources.

“There’s more resources out there to know where the lead is coming from, how they’re getting it, where you could go get more info, [and] how you could get more help,” she says.

CPS is scheduled to complete testing of 526 schools by the end of 2016, according to district spokesperson Emily Bittner, who noted that final results from all tested schools will be complete in early 2017. As of December 5, ninety-five school drinking fountains and eighty-nine sinks—thirty-two of which were in kitchens—tested above the EPA “action level” of fifteen parts per billion. Of the 184 fixtures above that level, all were shut down and more than 120 have been returned to service after pipes were flushed, repaired, capped, or replaced, according to school officials. The Chicago Park District went through a similar process this summer.

For many parents and city officials, the full array of park and school tests was worth applauding.

“I have to commend the Park District and CPS for being so aggressive and testing the faucets and the sinks within their buildings and outside,” says Chicago Department of Public Health commissioner Julie Morita. “I think it’s an extra step to ensure the safety of the water.” She added that CPDH is currently working with CPS to mail letters, informational packets, and the results of tests in their schools to parents.

“What we’ve said is that the risk is low and yet if people want to be tested, they should reach out to their health care providers,” she says.

As of December, CPS has spent $1.9 million and anticipates spending about $2.3 million total for the first-ever system-wide lead testing of school water fixtures, but when it comes to the root cause of lead, Ehrman says the city will continue to see cases of exposure until it removes the lead service pipes and fixtures that bring water into schools and homes around Chicago.

Leading the Way

Cuffe Academy kindergarten teacher Jeanine Saflarski says she’s happy with how the lead-affected water fixture in her kindergarten classroom was capped and fixed by CPS.

Of the 141 of fixtures tested at Cuffe in August, three tested positive for lead. Two sink faucets, both in pre-K classrooms, tested between twenty-six and twenty-nine parts per billion, significantly higher than the EPA’s “action level” of fifteen parts per billion. According to Bittner, the third fixture tested below that level and was flushed along with all other water fixtures in the district.

But zoom out further and a more concerning picture emerges. In 2013, 7.6 percent of children tested from the Auburn Gresham neighborhood, where Cuffe is located, had elevated blood lead levels, ranking ninth out of Chicago’s seventy-seven community areas. Though experts say Saflarski is unlikely to encounter a severely lead-affected child in her kindergarten classroom today, many of the thirteen-year-olds graduating from Cuffe’s eighth grade this year were born during a time when nearly twenty-one percent—more than one in five—of Auburn Gresham children under the age of six who were tested had elevated blood lead levels.

Saflarski says a teacher is trained to notice the smallest, earliest signs of a learning disability. “You do everything you can in the classroom to try to meet modifications and needs,” she says, adding that teachers have protocols in place for kids in need of special assistance such as speech and occupational therapy. The school system even gives teachers lists of children with medical needs like food allergies, she says, which is not the case for lead.

But even if parents were to disclose their children’s lead poisoning, there is no official protocol for what teachers should do. Younger children may be eligible for the state’s Early Intervention Program, but according to a 2012 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “lead exerts long-lasting effects and the effect of lead on a child may not be demonstrable until the child is well into the elementary school years.” The CDC report lists research-backed recommendations for lead-affected people from infancy to the age of twenty-one, including specialized counseling to help with aggressive behavior, nutritional programs, chelation therapy in severe cases to decrease lead content in the blood, and individualized plans that identify, monitor, and assist children who have learning disabilities.

“I think it’s terribly concerning that CPS doesn’t have a policy,” Ehrman says. “The policy should include, number one, a memorandum of understanding, a formal agreement, between CDPH and CPS signed off by the mayor of the city of Chicago saying there will be integration of databases,” so that city agencies can share information to identify and help children affected by lead.

Many lead-safe schools recommendations are agreed upon by lead experts, and while CPS does not formally address any of these recommendations in its policies, the district “uses a process called MTSS (Multi-Tiered System of Supports) to identify any students with potential special needs,” according to Bittner.

But a comprehensive school policy on lead is not unheard of. The Connecticut State Department of Education, for example, has published policies designed “to clarify the role of schools in meeting the needs of children and families affected by lead.”

In fact, “developing school district policy and procedures regarding children who may be affected by lead” is first on a list of ten distinct ways schools can better serve lead-poisoned youth, according to the department’s website. Other points include educating school personnel, maintaining special-education resources, development of monitoring plans, and referral of lead-poisoned students to enrichment and eligible disability programs.

Likewise, school districts in Boston; Rochester, NY; and Columbus, OH all have posted, or are in the process of creating, policies for school-based lead safety. According to the University of California’s Lead-Safe Schools Guide, benefits of a policy include avoidance of unnecessary costs, open communication with parents, better-trained school employees, and evaluation of what works on a local level.

In Flint, MI, a class-action legal battle is currently underway alleging the local public school system is not providing services and interventions that could make a difference in the ability of lead poisoned youth to succeed.

“Since the full magnitude of this crisis became public in 2015, there have been federal and state inquiries, investigations, task forces, declarations, and appropriations. Yet there has been no effective response to address the needs of the thousands of children who attend Flint’s public schools,” the lawsuit alleges on behalf of fifteen children who were exposed to lead in Flint.

Espinosa, along with many other CPS parents, is worried about the same thing. If no cost is too high for the district to find and repair lead-contaminated sinks and drinking fountains in the schools, what about the costs of ensuring lead-poisoned children get the care they need?

Additional reporting by Timna Axel and Enrique Perez

This story was produced in partnership with City Bureau, a Chicago-based journalism lab.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.