The story of All Jokes Aside, the South Side comedy club responsible for the rise of many of the world’s most famous black comedians, is a story about the black experience. It is a story of pressures: those that come from growing up in a low-income area, that come from being a minority in an elite university, and those that come from corporate structures that don’t want you there. It seems that there could be no one better to tell this story than Raymond Lambert, a co-founder of the club and the last man aboard the sinking ship when it closed down.

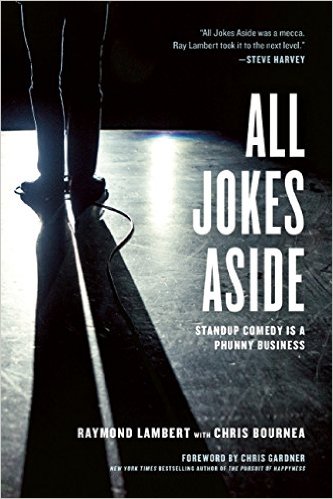

Lambert, who quotes classical philosophy as readily as comedy, states up front that he wants to work with entrepreneurs who want to make a difference in the world. In this book alone, he provides a number of lessons that could help not just those entrepreneurs, but anyone who deals with prejudice in networking and leadership. Unfortunately, this serves to make All Jokes Aside, the book Lambert has written about the club with Chris Bournea, somewhat disappointing. Deft at removing both emotion and conflict from many interesting stories, the book is all too ready to skip things that actually sound interesting.

All Jokes Aside was, to be reductive, a South Loop comedy club that flourished during the stand up comedy boom of the nineties. It was one of the favorite locations of Bernie Mac and Jamie Foxx and one of the first filming locations for Def Comedy Jam, which featured many comedians whose careers were formed by their relationship with All Jokes Aside. But the club was undoubtedly more than just a thriving venue. The late film critic Roger Ebert once wrote that, “what Second City was for Saturday Night Live, [All Jokes Aside] was for virtually every black comedian who emerged in the 1990s.” Even more than that, the venue was significant for its credibility as a business built by black people, for the black community. “It created a great feeling of pride among comics to have their own five star club,” comedian George Willborn says in the book. “The owners were black, the audience was black, the waiters and waitresses were black, the deejay was black. And they did not have to make any excuses for it.”

The authors point out that the comedian Laura Hayes once said that All Jokes was “the one club where she didn’t feel sexism.” Unfortunately, like many other stories I’d like to have read, the book skips over how a culture like that was created at the club. The book champions end results, yet details none of the conflict or triumph that led to them. Despite the fact that this book at times is more of an instruction manual on entrepreneurship than a true narrative, we don’t even get a cursory explanation of how to make that happen. Specifics are similarly lacking in the both the book’s discussion of All Jokes Aside’s leap to finally making a regular profit, and Lambert’s admission that he radically overestimated his initial profit stream, a mistake that nearly bankrupted them.

It sometimes feels like Lambert originally meant to write not a memoir, but a book of lessons for the African-American entrepreneur. Through anecdotes, he extolls the virtues of networking, especially within his close circle of fraternity brothers. He describes the benefits of business school, which include “an excellent education, great contacts, and the benefit of its reputation.”

I’d recommend this book to any entrepreneurs I know, especially fellow African Americans and anyone planning on a career in the entertainment industry. Perhaps one shouldn’t be surprised, but Lambert’s writing is at its most emotionally impacting when getting to the heart of his lessons in entrepreneurship, whether it’s his sobering description of the typical entrepreneur or his descriptions of the “black tax.” Even the club’s closure is written not as a tragedy, but as a lesson in business management. When Lambert opened his second venue, the challenges of being a black entrepreneur became emotional as well as instructional for him. He was praised by his neighbors to his face but found his hopes of starting a comedy club in the Loop destroyed by concerns that “the economic status of the clientele” would not be “conducive to the neighborhood.” It’s here that he addresses the “black tax” at its most devious and explains why he could never do things “the Chicago way.” It’s here that you can feel the frustration and sadness that he experienced.

Despite Lambert’s MBA-tinged writing style, he manages to provide insight into the urban black experience. Exactly how he connected with the black community becomes clear through many of his anecdotes, like one about a comedian getting his very first suit in order to be able to perform there. “A comedian could look out into the audience,” he writes, “and see his doctor at one table, his drug dealer at the next, his girlfriend at the next and his college professor at the table next to her.”

The story of All Jokes Aside runs through the center of what Chicago can mean as an incubator for black entrepreneurs. As Chris Gardner, a businessman and one of Lambert’s first employers said, “there wasn’t nothing unusual about a young African American coming to Chicago with a vision and a dream.” Lambert’s book, All Jokes Aside, perhaps should have been billed as an instruction manual for making it here, as it prioritizes the delivery of lessons over a narrative telling of Lambert’s story, and delivers its most powerful moments in passing down those lessons. Though a frustrating read at times, it is a book that deserves our persistence, as it has the capacity to teach us something.