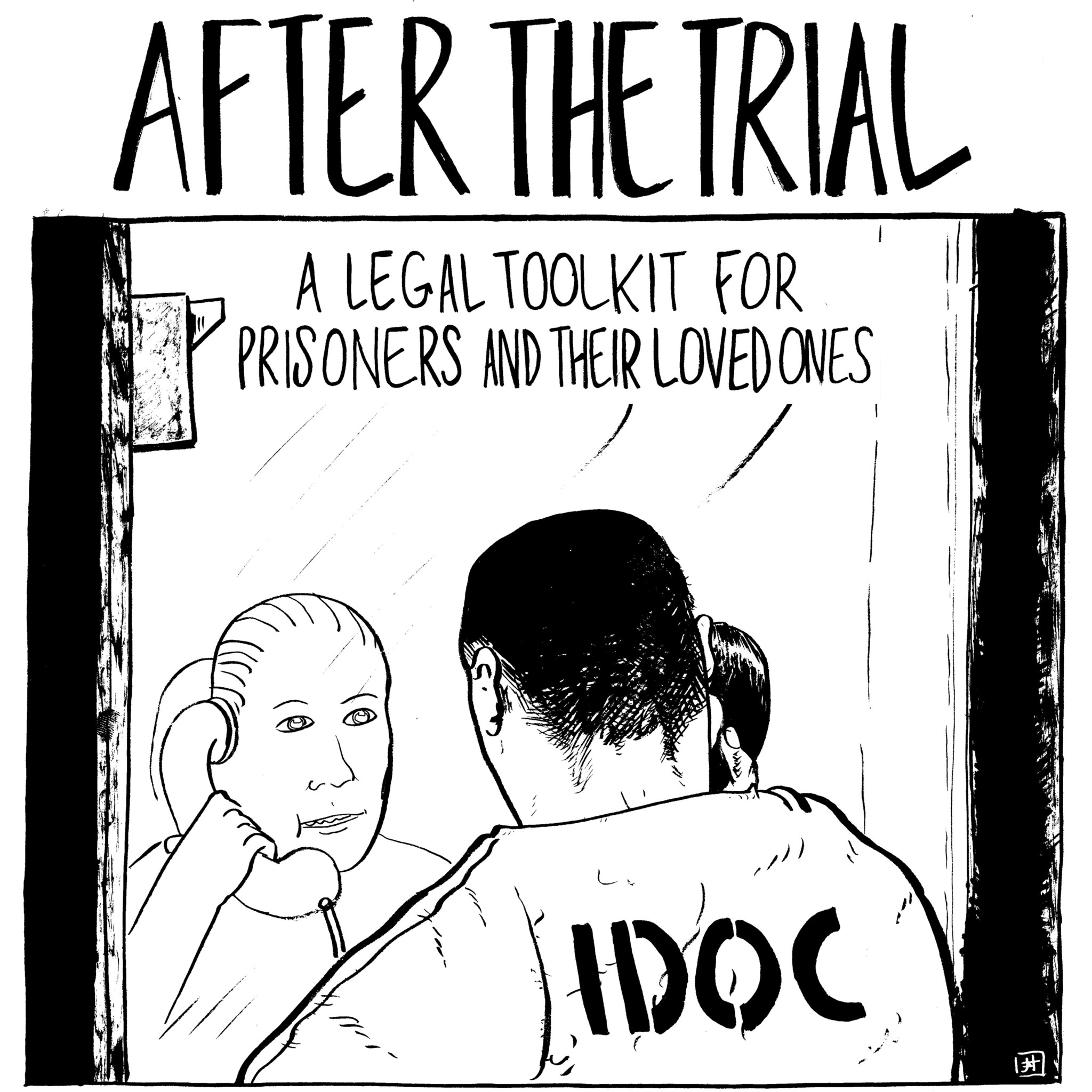

This is an excerpt of a forthcoming zine written by a team of reporting fellows at City Bureau, a civic journalism lab in Chicago focused on serving the South and West Sides.

In Spring 2018, our reporting team (Manny Ramos, Ellen Mayer and Bashirah Mack) tackled a project about post-conviction litigation and the difficulty of arguing that your lawyer did an inadequate job of defending you. As part of that project, we’ve spoken to lawyers and judges about legal procedure, we’ve gotten access to legal resources that aren’t accessible to most people and most importantly, we’ve spoken to formerly incarcerated folks about the needs and challenges of prisoners trying to represent themselves. We’ve compiled all that information into a zine, in the hopes that it will be useful to incarcerated people and their loved ones. We’d like to thank Westside Justice Center, a non-profit legal services and legal education organization, for factchecking and assistance in the creation of this zine.

The full twenty-four-page zine zine is currently being finalized and will be available to the general public in August. To request a free copy of the zine, which includes much more information for prisoners and their loved ones, click here.

Going It Without a Lawyer

In Illinois, anyone who has been charged with a crime has the right to free legal representation for their trial and for the direct appeal. That means the courts will provide a public defender to anyone who can’t afford a lawyer. After the direct appeal, you’re on your own.

At this point, folks who want to pursue post-conviction legal action will have to either pay for a lawyer, find an organization that will do pro bono (free) legal work or represent themselves. Many prisoners can’t afford a lawyer and pro bono organizations can only take on a handful of cases at a time. Some folks simply prefer to advocate for themselves. Whatever the reason, many prisoners end up representing themselves in post-conviction legal action once the direct appeal is over. Another term for this is “pro se litigation.”

If you’re representing yourself, you’re not alone. But you are facing a steep uphill battle.

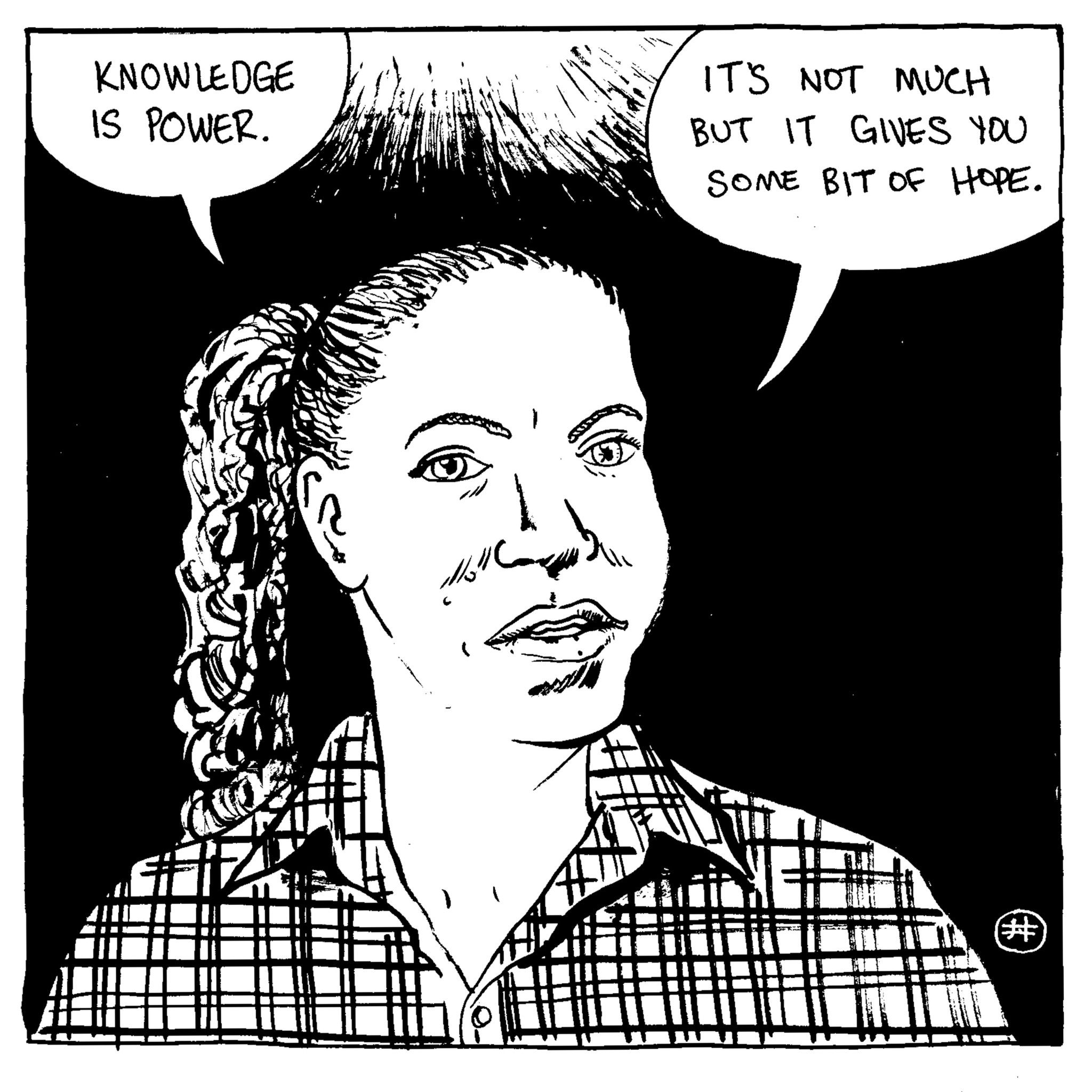

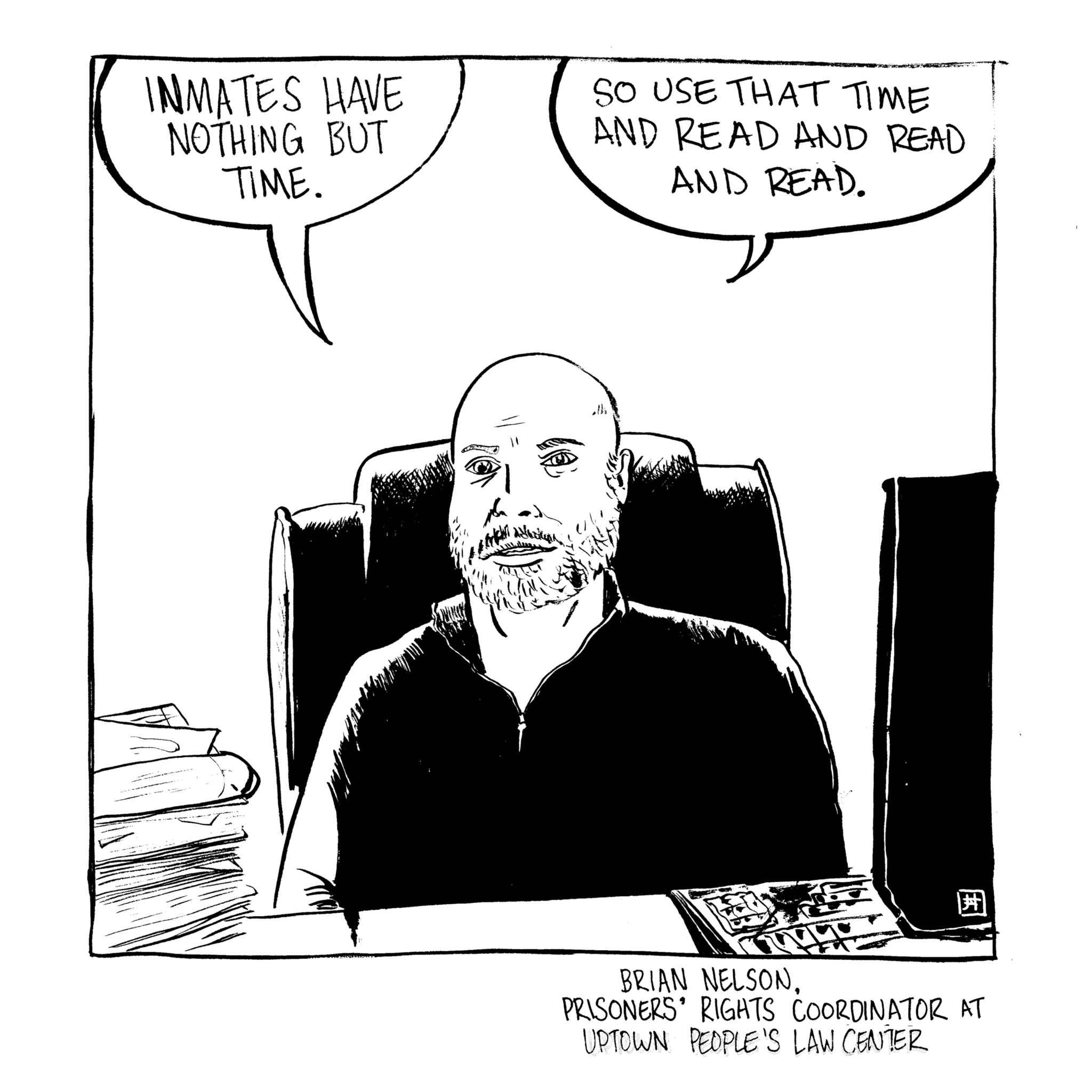

Lawyers go to school for three years just to learn the laws and procedures that make up our legal system. If you don’t have that formal training, you’re already operating at a disadvantage. That being said, there is a long and rich history of “jailhouse lawyers”—incarcerated people who have taught themselves the law and used that knowledge to get relief for themselves and their fellow prisoners. If you’re trying to join their ranks, the first thing you’ll have to do is learn the rules.

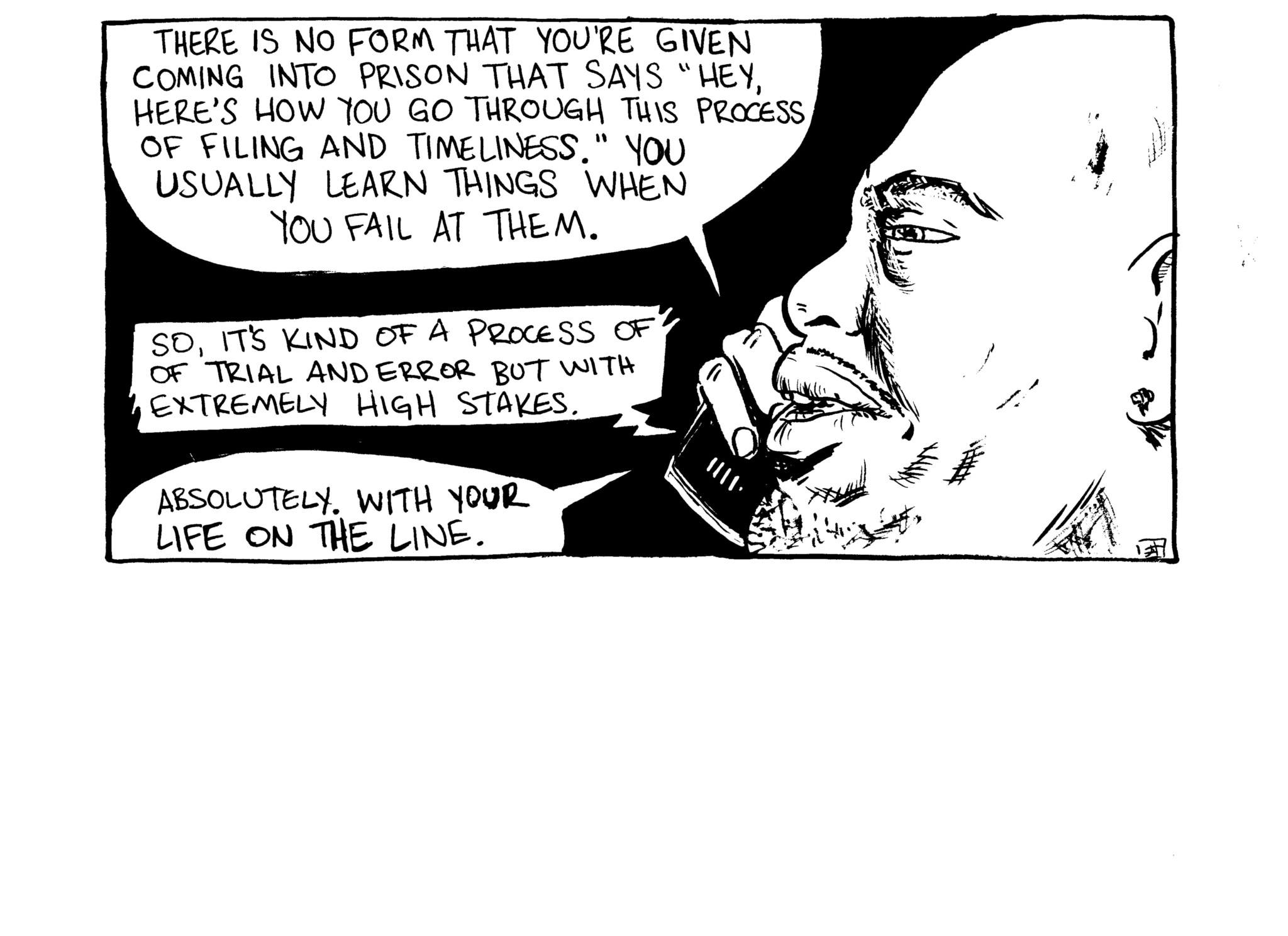

The courts have strict filing deadlines and rules for what you can and can’t argue in your post-conviction briefs. And there are steep penalties for breaking those rules. For example, if you file a post-conviction petition late, the courts will dismiss it, and you may never get a chance to file another one. Or, if the court finds that your petition is “frivolous” (without legal merit), you’ll be required to pay all of the filing fees and court costs and the department of corrections can revoke your sentencing credit.

Unfortunately, that means that there’s no room for trial and error. If you’re filing for post-conviction relief, you have to get it right the first time.

That sounds like a lot of pressure! But we’re not trying to discourage you. Actually, we’re trying to encourage you to do as much research as possible and get as much help as you can. If you have access to a good law library in prison, use it and ask the librarian lots of questions. If your fellow inmates are willing to share their own post-conviction experiences, learn from their successes and failures. If you have family or loved ones who want to help you, let them.

What to Know as a FamilyMember or Loved One

The courts can be overwhelming and intimidating. When you talk to lawyers, it may feel like they’re speaking a completely different language. Without legal training, you may feel like there’s nothing you can do to help your loved one file their petitions. But in fact, you can be an incredible asset to your loved one if you are willing and able to get involved.

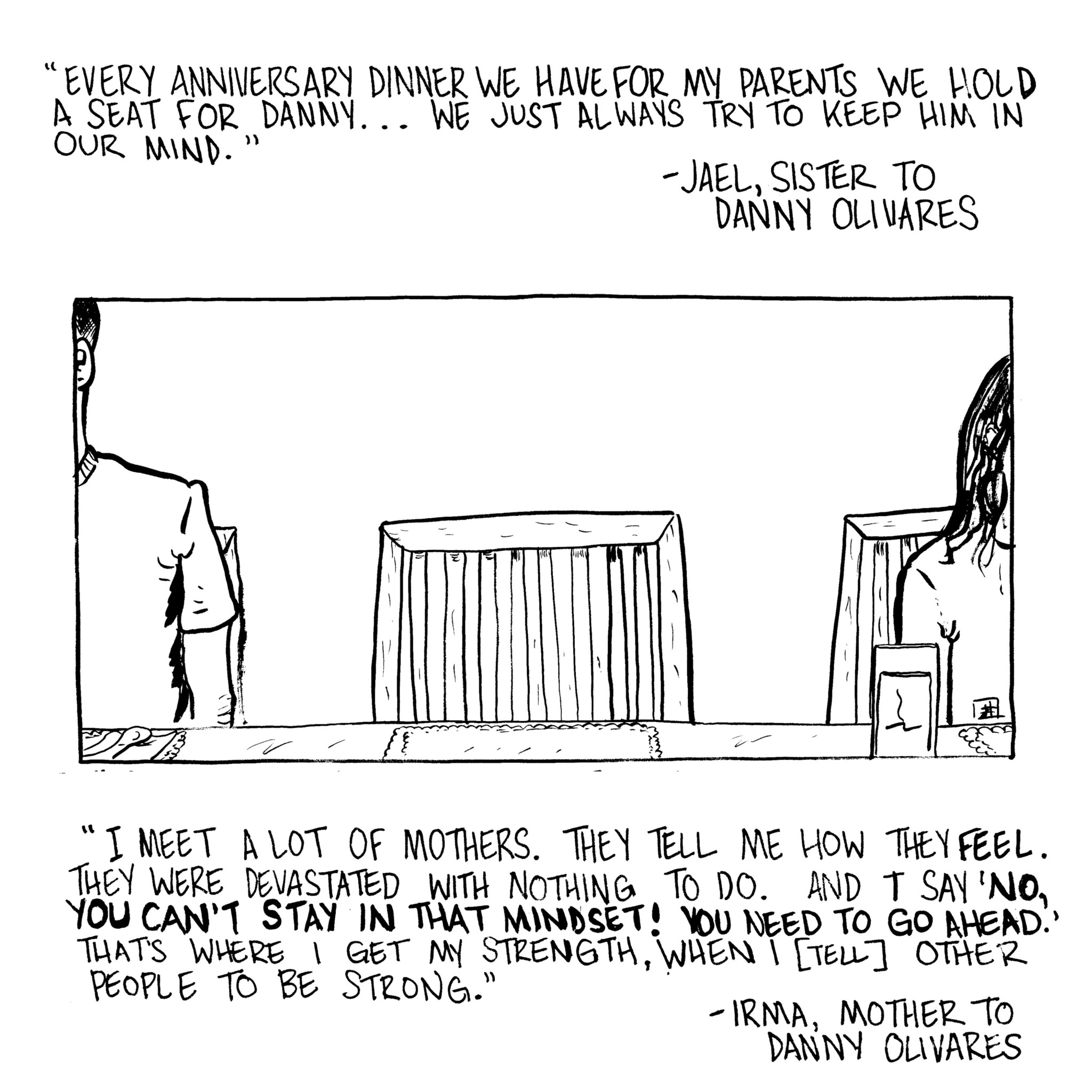

Of course, even if you want to help, your loved one may prefer to operate solo. He or she may not want to burden you or might just feel a sense of urgency to get it all done. Chicagoan Danny Olivares was convicted of murder when he was twenty-one and has been trying to fight the conviction ever since. When Danny lost his appeal, he wrote his own post-conviction petition. His sister Jael said he didn’t ask for much help. “I think he didn’t feel that anyone was as invested in [his freedom] as he was,” she said. “So he kind of just decided to do it himself.”

Ultimately, Danny’s family did help out in a few ways. They sent him legal books and they helped him make copies of his post-conviction petition. They also helped Danny get affidavits (sworn statements) from witnesses in his case.

If you’re planning to take an active role in your loved one’s legal fight, make sure he or she knows that you want to help and offer some ideas of how you can help.

For example, throughout this zine, we are going to emphasize the importance of doing legal research. But, depending on where your loved one is incarcerated, there may be very limited legal resources. For example, Danny Olivares told us that in Illinois’ Stateville Correctional Center, inmates can only access law books if they know the exact name of the case they want to read. Prisoners in solitary confinement have to request that books be brought to their cell, which can take weeks.

Without regular access to law books or the internet, your loved one may have a lot of trouble doing the research necessary to write a strong petition. You, on the other hand, can access the internet, either at home or at a public library. That, in and of itself, is a huge advantage. Once your loved one decides what kind of claim he or she wants to bring in litigation, you can help identify the most relevant court cases to read with just a quick Google search. You can visit Cook County’s public law libraries and ask the librarians there for help finding the most up-to-date case law.

Identifying case law is just one way that you can be helpful to your loved one. He or she might also need help accessing legal resources, contacting witnesses or finding new evidence.

Of course, all of this work takes time and money, and it can have an emotional cost, too. Orlando “Chilly” Mayorga is the director of CAVE (Chicago Anti-Violence Education) at Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation in Englewood. Chilly is also a former prisoner, and he said he wishes someone was checking on his family back then and letting them know they weren’t alone in this experience. “It would have been good for them to have somebody to walk them through not only the legal process but everything that comes with it,” he said. “I know how emotionally and psychologically taxing that was.”

Below, we’ll give recommendations for books and resources you can use for further information. And on top of that, we recommend that you seek out and learn from other people who have loved ones in prison. We’ve included contact information for organizations in the Chicago area who provide support and community to the loved ones of incarcerated people.

Resources for Families and Loved Ones

Legal Resources

Public law libraries

Cook County operates a public law library to serve lawyers as well as people who are representing themselves in court and the public as a whole. There are 6 branches of the law library, spread throughout cook county. The main branch is located in the Daley Center in downtown Chicago. You will find the best selection of books at the main branch, but every location has computers with Westlaw and LexisNexis, two online legal research tools that the majority of lawyers now use to find relevant case law for their cases. In addition, every location has a librarian on staff who can show you how to use Westlaw and who will help you conduct your research. The main law library in the Daley Center also holds regular educational programming that may help you with your legal research.

You can find your closest branch library here.

Legal Aid of Illinois Online:

The Illinois Legal Aid website contains tons of helpful resources including fillable legal forms and basic explanations of appeals, post-conviction petitions, etc. If you’re looking for a simple template for affidavits or motions (e.g., motion to proceed as a poor person) you can find those in the Form Library section of their website. The website has Spanish language as well as English pages.

Legal Aid self-help centers:

Legal Aid of Illinois also runs Legal Self Help centers around the state, including 4 in Cook County. These centers have computers with internet that are available for public use, and they usually have someone on hand to help you find legal forms and information on the Legal Aid Website. This is especially helpful if you’re having trouble navigating the website on your own. You can use the Legal Self-Help Directory on the website to find the location closest to you.

Printing and Copying

Chicago Public Library:

Website: chipublib.org/faq/printers-and-copiers

Printing and copying: 15 cents per page

Scanning: free

Cook County Public Law Library:

Website: cookcountyil.gov/service/legal-research-ccll

Printing and copying: 15 cents per page

Scanning: 15 cents per page

Illinois Legal Aid Self-Help Center:

Website: illinoislegalaid.org/get-legal-help/lshc-directory

Printing: Available at some locations. Free at some locations for legal information and forms only. Check the Legal Aid website to find out which centers have free printing services.

Social and Emotional Support for Prisoners’ Loved Ones

Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation

Precious Blood offers multiple services for families of incarcerated people. The organization occasionally coordinates family visits to Illinois prisons. In addition, it hosts a monthly gathering called Communities & Relatives of Illinois Incarcerated Children (CRIIC). CRIIC offers support, encouragement, and community to anyone who has a loved one in prison. PBMR also provides reentry services for the formerly incarcerated. Contact Julie Anderson to get involved: criic.julie.@yahoo.com.

Cabrini Green Legal Aid

Cabrini Green Legal Aid offers a monthly Reunification Ride, taking children—along with their caretakers—to visit their mothers in Logan Correctional Center. Loved ones of incarcerated folks can sign up for the program by calling Jessica Newsome: (312) 850-4621. Mothers at Logan can sign up by requesting a Reunification Ride form from their counselor.

Ellen Mayer is the Weekly’s politics editor and a former reporting fellow at City Bureau. This is an excerpt of a zine she wrote alongside her City Bureau team members Manny Ramos and Bashirah Mack. To request a copy of the full zine, please send an email to ellen.mayer@southsideweekly.com.

Jamie Hibdon is a cartoonist and illustrator who is part of the comics journalism collective Illustrated Press. His work can also be found in the ongoing anthology Lingua Franca Comics. When not making or teaching comics, he is probably thinking about comics.

When I walked through the front gate of the Attica State Prison in early 1972 to serve a life sentence, the prison was still in shambles from the notorious riot of 1971. In late 1972 the prison finally got around to establishing a functioning law library and I was assigned to provide legal assistance to those prisoners unable to help themselves; basically I functioned just like a lawyer, For a few years I was actually court-appointed to represent other prisoners in certain kinds of legal proceedings. I kept this job in prison law libraries all across New York for the next 40 years until my parole release. Along the way I became something of an expert in post-conviction practice. I won a lot of cases and I’d like to pass on a couple of tips for jailhouse lawyers who may not already be aware of them.

First, when you draft your papers, concentrate on clearly stating the facts of your case without obvious bias. The judge presumably knows the law, but the judge doesn’t know the facts of your case like you do.

Second, tell your story using short sentences and plain English. Don’t showboat using big words. Write as though you’re explaining your case to a teenager who knows nothing about law and has a short attention span.

Third, writing skills can be more important than your legal research skills. I knew a lot of men who were very competent legal researchers and had a good grasp of the law but were terrible writers. Judges are not known for their patience in trying to figure out what you’re trying to say.

Fourth, be prepared for potentially devastating set-backs. Been there, done that, and I survived. You can too. And if you’re good enough, you might be able to help other prisoners who don’t have your skills. I’ve been out of prison for almost seven years and I continue to write motions and appellate briefs for lawyers, so for a few ex-cons post-release employment in this field is a possibility.

One other thing: nobody ever overturned their conviction by hanging in the weight yard, on the basketball court, or chasing the bag. Priorities matter.