Profundity is a dangerous thing to chase. It’s a bit like chasing one’s own tail, in that its circular motion is naturally opposed to the vertical movement depth requires. There’s nothing shallower than the desire to be profound.

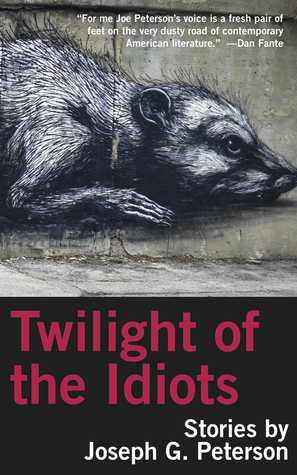

Twilight of the Idiots, a new collection of short stories by Joseph G. Peterson, proclaims its ambitions toward profundity with such gusto—a Nietzschean title and epigraph, plus an invocation of Homer on its back cover, for starters—that it feels unfair to expect it to live up to these intentions. But it’s clear from the get-go that Peterson, a Chicago-area writer with four novels under his belt, is aiming high.

At first glance, an interesting unifying motif emerges in the form of calls to action from mysterious sources (vagrants, hallucinations, alcohol, the Muse, and so on). There are universal concerns: mothers and fathers, the relations between men and women. In other words, suitably rich material for an ambitious project.

Peterson’s choices, however, quickly limit the collection. Despite there being eleven stories, we get only male narrators and protagonists. In a collection that makes pretensions of saying something about men and women, love and loss, life and death and the rest of it, this is problematic, limiting, and lopsided.

The damage done by the gender imbalance is doubled by the uniform disdain Peterson’s menfolk have for womankind. These are angry stories of immaculately beautiful women leading men to ruin, of cheating wives, of traitorous mothers and girlfriends, of older women preying on young boys, of men relentlessly misunderstood and tormented by nagging. There are exceptions—specifically, the few stories that exclude women entirely: a cop on-duty, an ex-soldier (men’s work, surely), and a few murderous gangsters (same thing).

More troubling is when these tendencies emerge in full: the further down the socioeconomic ladder, the more regressive attitudes the character spouts. This feeds into another disconcerting aspect of Peterson’s work: the odd and severely off-point attempts at a blue-collar dialect. Even ignoring the occasional dissonantly hifalutin’ phrase thrown in, these sections seem like an educated person’s fantasy version of how commoners speak; one can only assume their sexist conservatism is meant to feel somehow innate. The use of this device is hardly progressive, but more importantly, the rhythm in the dialogue is so off that the effect doesn’t even work as intended. The stories that lean more heavily on the dialect are easily the most painful.

Really, though, it seems that Peterson is not playing to his strengths in this collection. This is his first collection of short stories, and the rhythms of the short form evade him. The shorter stories in the collection are almost all dialogue, with heavy use of clichés and archetypal characters. Perhaps this is intentional, to give the stories more of a “universal” quality, but for reasons already mentioned, these pretensions largely land with a thud. Even if the characters’ voices, regardless of their ages, weren’t so oppressively similar, the dialogue in the shorter pieces all seems insufficiently motivated, the characters’ decisions too arbitrary. Nearly all of the stories end with somebody dying, too, which is this form’s equivalent of ending every scene in a movie with somebody leaving a room.

This is a shame, because the one piece that gives itself a little more room to breathe, “Rawfish,” is easily the best of the lot—not coincidentally, it avoids many of the pitfalls mentioned thus far. It’s a simple story of a boy’s first job, somewhat reminiscent of John Updike’s “A&P.” Granted, an immaculate virgin/grizzled harlot dichotomy scaffolds the story and threatens to derail it: Charlie takes the fish restaurant job to impress a “dauntingly pretty” girl with “fragrant hair” (she’s devoid of personality, of course), and has as a coworker, Beverly, an older woman with a “thick coating of makeup” and “fake lashes” who nearly propositions the sixteen-year old narrator. But the narrative voice holds convincingly, and the story moves swiftly, with interesting exchanges and clever details. Motivations are allowed to arise and subside organically, the plot grows in suspense, and in the end, Beverly’s dignity somehow manages to overcome the indignities of her characterization.

The narrator leaves the story with a new respect for her and for himself, a new lease on life. We leave the story with hope for this author, that he may tap into his strengths more effectively, and furthermore raise himself above some rather puerile hang-ups, predominantly about women. Until he can do that, it can’t surprise us that his most convincing vignettes come in the voice of a sixteen-year-old boy.

Joseph G. Peterson, Twilight of the Idiots. Chicago Center for Literature and Photography. 226 pages.

Linus, as this book’s publisher, I feel compelled to take great umbrage at the amount of scorn you’ve heaped upon this book for it containing unlikeable characters, when in fact this is the entire point of this book’s existence, as clearly stated in both the book’s back-cover synopsis and in the very title itself. To give a book a bad review merely because you don’t like the general idea of stories featuring unlikeable narrators is in my opinion a really unfair thing to do, akin to panning “Moby-Dick” because Ahab is “unpleasantly obsessed with whales.” You’re of course welcome to have whatever opinions you want about Joe’s actual writing style, his treatment of blue-collar slang, and the other things you complain about here (all of which I disagree with as well, although that should be obvious), but I feel it’s my duty to mention how unfair you’re being as a supposedly “objective” reviewer to give this book a pan merely because the narrators of the stories are unpleasant people, especially when that was the entire goal the author had in mind from page one, and explicitly states so right in the book’s very title.

I was sad to read this review; it is difficult to assign reviews and Lord knows there are so few reviews in the media today, so all readers are grateful. I think (and I do not know, of course) that the reviewer is quite young; I went ahead and read his story about the lion who bit the throat of man of this website and I thought of Ray Bradbury and what, in relation, a review of that story might be. I happened to get a copy of Joe Peterson’s collection and loved it. I am middle aged. I have a wife and daughter and son and love them all very much. The first story in the collection is perhaps the best short story I have read of what a woman feels at being treated as an object; clearly, as the first story—which is the table setter—was not understood by the reviewer. I imagine this is to youth, but it might be inexperience; I do not know. The next is perhaps the best story I have read on suicide. Whew. I agree that Raw Fish is an excellent story, but I thought others better. It is of course a matter of taste. The reviewer encourages Mr. Peterson, but as far as I am concerned, this is an extraordinary short story collection.