During last month’s walkout and “Day of Action,” activists and teachers from Chicago Public Schools (CPS) gathered at two of the city’s public universities, Chicago State University (CSU) and Northeastern Illinois University, to advocate for increased funding across the education system. They protested a state budget crisis that has not only left Chicago Public Schools stretched thin, but also left public universities, including those two, without any state funding for most of the 2016 fiscal year.

Beyond the parallel situations of CPS and Illinois public universities, CPS educators have another reason to protest the defunding of Illinois public universities: these are the four-year institutions that their students are most likely to attend.

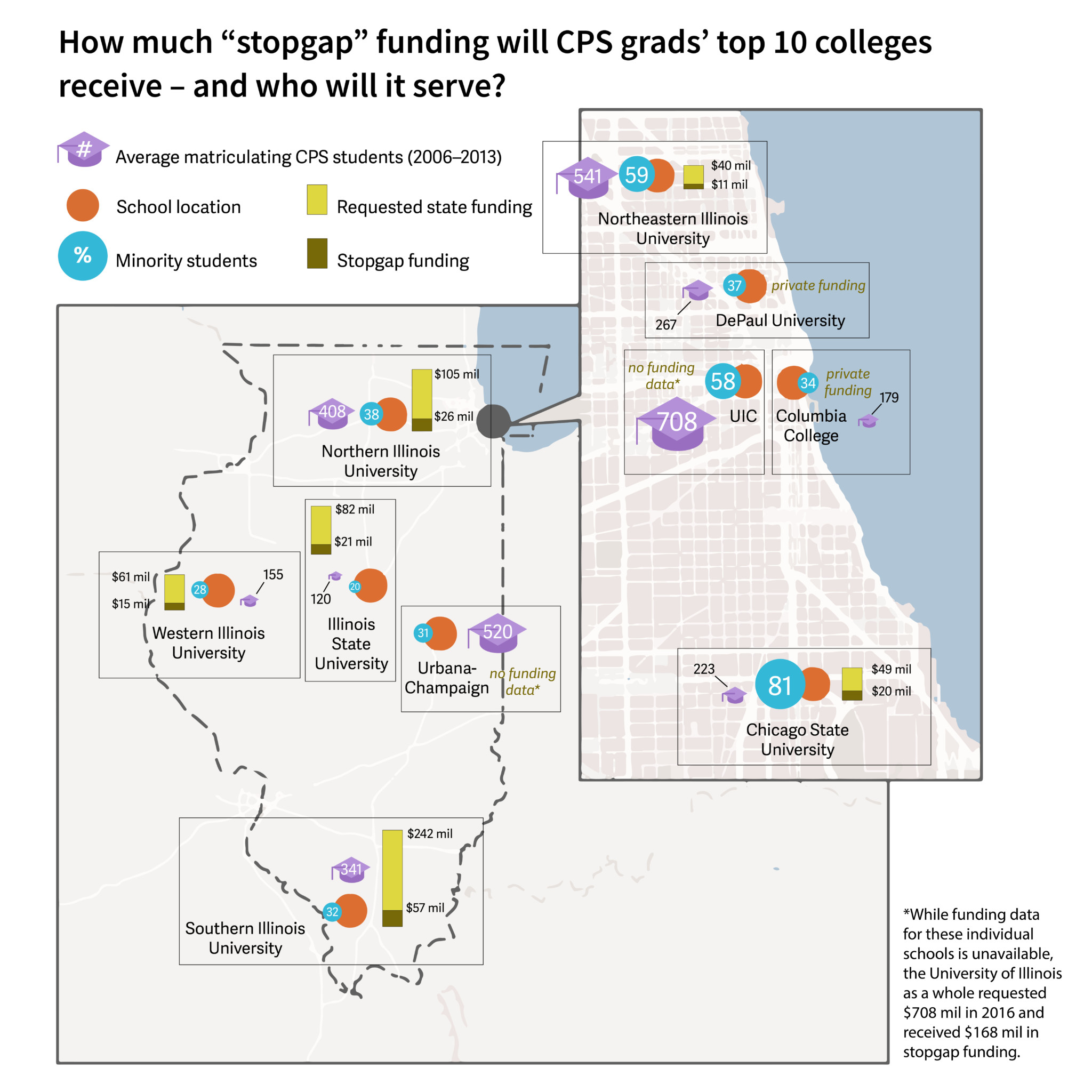

A 2014 report from the Chicago Consortium on School Research (CCSR), entitled “The Educational Attainment of Chicago Public Schools Students: A Focus on Four-Year College Degrees,” highlights the somewhat troubled path CPS students face between graduating high school and completing a bachelor’s degree. As part of its analysis, the report lists the top ten four-year colleges and universities attended by CPS graduates, ranked by average number of CPS enrollees between 2006 and 2013. Of the ten schools, all are located in Illinois and eight are public universities, five of which are located outside of Chicago.

CSU, a majority-minority school pushed to the brink of shutdown without state support, is arguably the hardest-hit by the budget crisis. Like all nine of Illinois’s public universities, CSU finally received public funding on April 25, after Governor Bruce Rauner signed a stopgap measure that provided $600 million to the state’s public universities, community colleges, and its low-income student scholarship program, the Monetary Award Program. But just four days later, on April 29, CSU announced layoffs for 300 non-faculty employees, and even more layoffs might be coming.

But the other public universities on the list are facing their fair share of uncertainty. None of these schools received more than half of the funding they requested before the start of the fiscal year—with the exception of CSU, stopgap funding for each school hovers around a quarter of the requested amount.

Most schools have had to cost-cut to make it through the end of the spring semester; many of them based their decisions on Rauner’s proposed budget cuts, which still offered more funding than the stopgap measure that passed in late April. At Northeastern Illinois University, ranked number two on the CCSR’s list, all administrative and non-union employees have been working without pay for one day a week since March; hiring and spending freezes are also in place. In February, its credit rating was downgraded by Moody’s Investors Service.

Outside of Chicago, Northern Illinois University also had its credit rating downgraded, and it cut over $15 million from its spring semester budget. Southern Illinois University at Carbondale plans to lay off 180 people and make cuts to academic and student employment programs. The school also attributed a decline in enrollment for the spring semester to the state budget crisis. Western Illinois University announced plans to cut $20 million from its budget over the next two years, lay off 110 employees, and institute a hiring freeze; these plans have not been changed by April’s stopgap funding.

The University of Illinois system, whose campuses are ranked number one (Chicago) and number three (Urbana-Champaign) on the CCSR list, received only a quarter of its requested funding. Since the schools have relied on state funding for only ten percent of their budget, and have greater endowments than most, they are relatively better-off than their peer institutions. But even these schools have faced cuts—in October, the University system cut $24 million in administrative costs, and in April, UIUC asked departments to prepare for layoffs in the fall. Illinois State University has also faced relatively minor shortfalls—the school instituted a partial hiring freeze and in May announced a three percent tuition increase for next fall.

Most schools say that April’s stopgap funding is only a fragment of what they need: they hope for additional funding from the state before the end of the fiscal year in June. In the meantime, students at these schools will work toward their degrees under constrained circumstances.

The CCSR report paints a rather dismal picture of college-degree attainment for CPS students. Seventy-three percent of CPS ninth-graders graduate high school, and forty percent of those graduates enroll at a four-year institution. Even then, many students who make it to college leave without a degree. Just below fifty percent of the college enrollees graduate within six years—just fourteen percent of that original ninth grade class.

These low rates of college success indicate problems not only in higher education, but at the primary- and secondary-school level; they predate the precarious 2016 fiscal year, and they will likely persist in years to come. The road from CPS high schools to a four-year degree is clearly rocky—but this year’s funding crisis for public universities makes it that much harder for Chicago kids to succeed in the schools they most commonly attend.

It would be interesting to see the tuition rates and how they changing at each university. Is it true that Illinois tuition is twice the US average?