John Edel first fell in love with Chicago’s industrial history—“factories and railroads and ships,” he said—as a boy growing up in Rogers Park. He spent his youth following that curiosity, whether he was reading classic histories of the city or exploring abandoned factories in Skokie and Lincolnwood. Later, he discovered books like William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis and Louise Carroll Wade’s Chicago’s Pride: The Stockyards, Packingtown and Environs in the Nineteenth Century, which explored the ties between Chicago’s environment and its economic development.

This early love of industrial history, coupled with an MFA in industrial design from the University of Illinois at Chicago, led Edel to found Bubbly Dynamics, a limited liability corporation with a social mission: to renovate dilapidated manufacturing facilities in environmentally responsible ways and create sites for small and emerging businesses. His first project, the Chicago Sustainable Manufacturing Center—better known as Bubbly—now houses about a dozen light-industrial manufacturers in an affordably renovated Bridgeport building with a green roof.

In 2010, Bubbly Dynamics bought the old Peer Foods pork processing plant located at 1400 W. 46th Street. The goal was to house modern food-producing businesses in an energy efficient and low-waste building with a closed-loop approach to agriculture. Edel’s vision for the building—today known as The Plant—also included a museum “about the history of the area and the building of the Stockyards.”

It took a bit more than a decade, but the pocket-size Packingtown Museum now sits deep within The Plant. With the help of curator Dominic Pacyga, author of Slaughterhouse: Chicago’s Union Stock Yard and the World It Made; curatorial assistant Ivan Guzman; and others on a small committee, the Packingtown Museum opened in 2021.

The free museum, housed within just one room but extended by hallways, pays tribute to the waves of workers that arrived in the neighborhood across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries through immigration and the Great Migration. Attracting visitors from both down the street and around the world, the Packingtown Museum also serves as a gathering space for community groups, including the Back of the Yards Peace and Education Coalition and the Creative Chicago Reuse Exchange.

Today, Dominic Pacyga is professor emeritus of history at Columbia College. But back in 1969, he was a livestock handler, working second shift in the waning days of the Union Stock Yard before its closing in 1971. Pacyga grew up at 45th and Wolcott and knew Back of the Yards well. But he studiously avoided the Peer Foods building, which had brought tragedy to his Polish immigrant family.

“My grandfather got hurt at the plant in 1948, and later died of his injuries. I stayed away from the area,” he said.

But later, a film crew persuaded Pacyga to discuss the history of the Stockyards at The Plant during the early days of redevelopment. Pacyga and Edel met and quickly became friends.

“When it was time to get serious, Dominic was the logical choice” to curate the Packingtown Museum, Edel said.

“It’s a small museum, but I think it tells a powerful story and [offers] a rich history of the neighborhood,” said Pacyga. Many of the photographs come from his personal collection, including a picture of his grandfather.

In Pacyga’s view, two overarching themes run throughout the history of the Stockyards: the innovation, and the spectacle. Today, the Stockyards Industrial Park is an imposing site from most angles—and especially near 47th and Racine, where Testa Produce’s wind turbine sits just a few hundred yards from a large, smoke-spewing plant that looks straight out of a Simpsons episode. But there are large areas of vacant space.

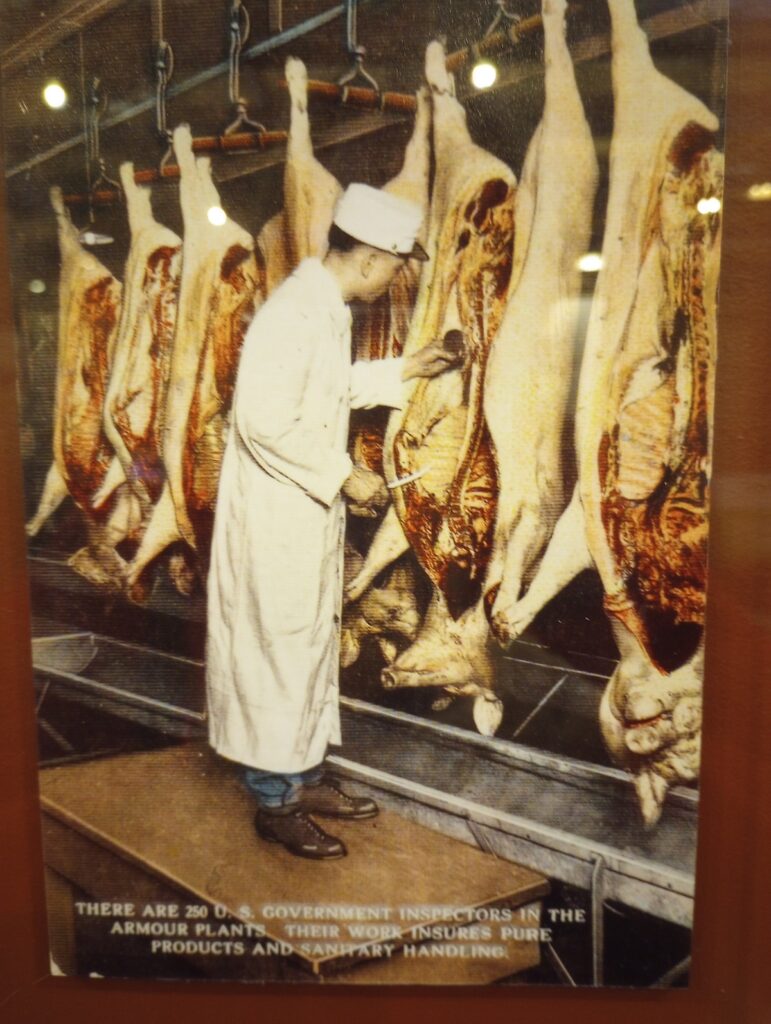

Not so in the glory days in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “It was a big tourist attraction,” Pacyga said. “Half a million people a year were coming every year to see the Stockyards and the killing floors.”

At Peer Foods, pig carcasses were hung on the meat rail and sent down the packing line to be carved up and sold, whether in products like bacon and sausage or in pieces. As Pacyga tells the story, a kosher butcher from one of the meat companies would carve artisan works out of bones, “like a cane and a jewel box.” Those items are now part of the museum’s (deliberately small) collection.

Pacyga knows all the fun details you might never have guessed about the Stockyards—from the fact that the Chicago White Stockings, predecessor of the Cubs (not the Sox!) played their first game in Dexter Park on 43rd Street just off Halsted, to the trivia-worthy date of Christmas Day 1865, when the Yards first opened to the public and crowds jostled to see cattle being slaughtered and butchered.

Pacyga noted, wryly: “What better way to celebrate Christ’s birthday in the most capitalistic city in America?”

Ivan Guzman joined the Packingtown Museum effort in 2017. Previously a high school teacher, Guzman was then attending grad school at UIC for museum studies. “Creating a museum from the ground up seemed really enticing,” he said.

Building a museum inside The Plant, a historic packing plant being remade for modern food businesses, was also a draw. “The space we had was very unique, different from a traditional museum or gallery space,” Guzman said. “I enjoyed how the history was embedded in the space.”

The committee considered how to use the room’s unique elements, like the large cooler door in the back corner, to tell the story. “How do we use that, how do we embed that in the exhibit?” Guzman recalled them wondering. Their answer: the door opens to reveal an enlarged photo of a butcher on the line.

Edel said he deliberately left the meat rails on the ceiling in the space to enhance visitors’ understanding of the original building.

To enhance the immersive feel, Pacyga, Guzman and others are collecting stories from families who arrived in the Stockyards from elsewhere. Guzman is working on translating all the stories into Spanish. “We want to make sure the museum is language-accessible to Spanish speakers, given the makeup of the neighborhoods” nearby, he said.

The museum team acknowledged that it hasn’t always been easy to coax stories out of people. “Mexican families’ [stories] were a little easier to obtain because of the number of families living in Back of the Yards,” said Guzman. Though they have leads, he added, “We’ve struggled to find a German family story.”

Edel acknowledged the problem runs deeper than just finding the storytellers. Many people with great stories to tell turned silent when asked to record their tales for posterity. “People love to talk, but they’re too self-conscious about it to leave a record.” That was true of Jaime, a Peer Foods worker living down the street, who sent his children to college on the backs of the pigs he cut up. It was also true of Wanda Kurek, the beloved owner of Stanley’s Tavern, who passed away in 2019 at the age of 95.

“She would tell stories all day,” recalled Edel. “Then, when we finally came into the bar to record her, she was angry. We got one-word answers.” As soon as the recorder disappeared, she became her usual, talkative self.

Though the work has been difficult, the team continues to gather stories and plans to build an immigrant timeline featuring these stories both in the physical museum and online, at the museum’s website.

Pacyga noted that innovation and spectacle continue to play a major role in today’s Back of the Yards. Testa Produce, in the Stockyards Industrial Park, relies on a wind turbine to provide thirty-five percent of its energy. Surrounding the Packingtown Museum, inside the Plant, are a host of small businesses providing 105 full-time jobs. According to Eden, more than half the businesses are women-owned, and a third are owned by people of color.

Local coffee shop owner Jesse Iniguez, who grew up in the neighborhood, takes a nuanced view of the museum. “It’s a great opportunity to highlight the history and culture of Back of the Yards, both past and present,” he said.

At the same time, he and others in the neighborhood would like to see the museum, and The Plant, get more deeply connected to the community. “Maybe it’s because of the pandemic, but I think more could be done to invite the community.”

When asked directly about local concerns that a white North Sider showed up in the neighborhood, bought a building and is creating something that could change the character of the area, Edel spoke candidly. “That has, from the start, weighed heavily on my mind,” he said. “I’ve never had the intention to be a spaceship from the North Side showing up to gentrify the neighborhood.”

But growing really deep roots in the community isn’t easy. Edel, the Plant and the Packingtown Museum have made some headway, but with scarce resources, ensuring the museum is widely known throughout the neighborhood has been a lesser priority. “If we had a little bit more resources, I would love to have somebody whose job it was to shepherd school groups” through the working industrial site, Edel said.

For now, that task falls to Carolee Kokola, The Plant’s operations director, who joined the team in 2013. “I kind of have [an]ear to the ground as far as who is visiting,” she said. She said more than a third of visitors come either out of interest in Chicago history or in the history of meatpacking and its role in creating industrial processes. Another historical fun fact offered by Edel: Henry Ford’s car production line was just a riff on the template created by the meatpacking industry.

Though hosting school groups can be challenging, given that The Plant is an active industrial facility, Kokola mentioned that the museum recently hosted the eighth-graders from San Miguel School, a Catholic middle school in Back of the Yards. “We had like forty-something eighth-graders,” she noted. Many didn’t understand what the neighborhood name meant before their visit.

The museum already hosts some events, like April’s Reuse-a-palooza, and recurring meetings, like a recent gathering of the Back of the Yards Peace and Education Coalition. Edel wants to expand the museum’s programming to hold more lectures, film screenings and poetry readings with local and citywide organizations.

Guzman offered some advice to first-time Packingtown Museum visitors: “Before even stepping into the building, I would say, just take in the neighborhood.”

You can see—and often smell—the Chicago Meat Authority, still packing beef, pork and poultry, on 47th Street just east of Racine. Or grab a taco from La International, a grocery store at 46th and Ashland, at Paco’s Tacos in the back. Guzman advised: “Appreciate the neighborhood and the surrounding environment to understand the history that’s being presented in the exhibit.”

The Packingtown Museum is open Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Fridays, 9am. to 4pm, or by appointment. You can also visit the museum during tours of the Plant building, which are held every Saturday during the summer farmers’ market season. Or visit online at www.packingtownmuseum.org.

Maureen Kelleher is a writer who lives in Back of the Yards. Find her: @KelleherMaureen

Many Irish work there . They lived From Halsted and going east.