As musicians tuned their saxophones and violins, the Sunday morning service at St. Sabina’s, on 78th and Racine, began with an announcement: “If you want to get married at St. Sabina, you must attend our seminar, ‘Becoming One.'”

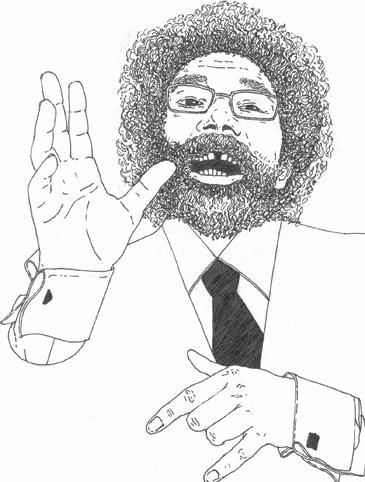

The church, known for its social activism under pastor Michael Pfleger, was packed to capacity for the annual visit of liberal intellectual Cornel West. State Senator Jacqueline Collins was in the audience, as was John Rogers, CEO of Chicago-based Ariel Investments.

“I don’t know about you, but I’m full of joy this morning,” said West, taking the stage as music rose.

He began his sermon with love. “I am who I am,” he said, voice deepening, “because somebody loved me. Somebody cared for me. Somebody tended to me, somebody targeted me.” West spoke of his family and early mentors as integral to his own past. “I’m a Christian, I believe in loving everybody. But I begin on the chocolate side of town!”

West rapidly blended religious, political, and social messages, while juxtaposing a bleak view of American democracy with a joyful genealogy of black leaders and an aficionado’s love of music. “The black freedom struggle is one of the great treasures of the modern world, and black music as a part of that tradition is one of the jewels in that treasure,” he said.

“And anytime that the quality of the music, the quality of the life, the quality of the love, the quality of the service is sacrificed, you can rest assured that not only is America in trouble, but your democracy is about to slide down the slope into chaos.”

Invoking Malcolm X and Angela Davis alongside James Baldwin and Billie Holiday, West pleaded with his audience. “Got to be honest! Got to be candid, frank, unintimidated, unafraid, say what’s on your mind! Say what’s inside of your soul! Just like our musicians at their best.”

“You can’t help but be a trouble-maker if you’re trying to be honest,” West said. “That’s what I love about Socrates: he was an honest brother.”

Here he turned to address the criminal justice system and the condition of young black men in America. “Three generations of young precious black and brown poor youth, largely destroyed but they’re bouncing back.”

“Where’s the holy angel?” he asked. “Where is the moral outrage, where is the righteous indignation of those who are serious about having integrity, honesty, decency?”

West used W.E.B. Du Bois and Martin Luther King, Jr. as examples of a legacy that must be continued and maintained. “That’s what I’m talking about. That kind of spiritual depth, and moral commitment, willing to live but also willing to die, but not dying in order to be a commercial, an advertisement, but because you love something bigger than you. And some love went into you! So that you allow yourself to be part of the life of the afterlife of the folk who loved you so deeply and sacrificed for you so intensely.”

“There’s no guarantee that the black freedom struggle will survive, with any level of honesty, decency, integrity or virtue, if the younger generation does not pick up the mantle…with a sense of remembrance for those who came before.”

“I don’t know how long I’ll be around, but I want the young folks to know, I might not be optimistic about America but I have great hope in them.”

As West moved away from the podium, Father Pfleger approached, and called up “any young brothers between sixteen and twenty-five” to join them on the altar. As they made their way up to the front of St. Sabina’s, young boys, teenagers, and grown men stood facing the congregation. “You are the best hope we’ve got,” Pfleger said.

“Make a promise to me,” said West. “Listen to Nina Simone’s ‘To Be Young, Gifted and Black’ when you get home.” After great applause, each man embraced West and returned to his seat—some smiling, some grave, but everyone looking as if Dr. West had given them a hug, a burden, and a benediction.