- Best Complimentary Dessert

- Best 100th Anniversary Celebration

- Best Youth-For Youth Undertaking

- Best Secret Garden

I was born in ’52. There weren’t a lot of new immigrants coming in, and at the time, everybody was being Americanized. In my family, we tried to keep the language and the culture going. My father wanted us to speak Chinese at home all the time, and we went to Chinese school every day for six years.

Susan Lee Moy is the author of The Chinese in Chicago: The First One Hundred Years, a book-length master’s thesis on the history of Chicago’s Chinese population. She was born in Chinatown, where she attended John C. Haines Elementary School. For junior high and high school, she attended schools on the North Side, and then for college, she attended Northeastern Illinois University, where she studied to become an elementary school teacher. After finishing her education, Susan taught in James Ward Elementary School in Bridgeport for sixteen years, following this position she became assistant principal at Solomon Elementary School on the Northwest Side for two years, and then principal for ten years. She retired five years ago.

[After college] I came back to Haines to teach for one year, and at the time, multicultural and bilingual education was coming to the forefront. I thought, if this is the way of education, then I needed to be more prepared, so I attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison and received my master’s in Asian-American History. My thesis was on the history of Chinese [people] in Chicago from 1870 to 1970. That was completed through a lot of research, but also [through knowing] my own family history.

Both of my grandfathers were here [in America] at the turn of the century. My grandfather [on my mother’s side] brought my grandmother to Chicago, one of ten [Chinese American] women [in Chinatown] at the time. [Ed. note: U.S. census data show fourteen Chinese American women living in all of Chicago in 1900].

My grandfather [on my father’s side] had worked in laundry. By the time my father came [to Chicago] in the mid-twenties, things were changing, and he didn’t want to be in the laundry business, so he started operating a Chinese restaurant. So that’s the family history. I did learn a lot from the stories my mom and dad told as I was growing up.

And I saw my father being very active in the Chinese community. He was president of the Lee Association and travelled a lot across the country, so I saw how the network of Chinese [people] across America worked through him. And my mother always loved history as much as I do. She was a teacher for one year in China and taught at the Chinese language school at the Chinatown Church. Because she was more literate than many of her contemporaries, she was able to pass that onto my brother and myself.

[From writing The Chinese in Chicago] I learned to appreciate the forefathers and foremothers before us and the sacrifices they had to make so that we can have a good living. When I grew up in the sixties and seventies, it was the wakening of Asian-American history, much like African-American history—everyone was finding where they were coming from. I had a lot of friends protesting, participating in the Vincent Chin marches, asking for equality.

I do remember my father saying to me, “You should always speak your culture and speak your language because we’re living in a Caucasian world, and wherever you go, people will look at you and associate your yellow face with being different from you.” And in a way, it’s true. I’m glad he taught us that and we’re able to then tell ourselves and others that we’re just as worthy as anybody else.

We try to pass that on to our two children. I have a son and a daughter, and they both understand a lot of Chinese. People are always like, “Wow, you’re the fourth generation and can still speak Chinese? That’s amazing!” Although I had moved to the North Side, I often brought my children to Mark Sheridan Math & Science Academy in Bridgeport, so that they could be exposed to other Chinese Americans like themselves. I think that was good for them; it gave them a sense of community, a sense of belonging.

I still go to the Chinese Christian Union Church in Chinatown. I went there for nursery school since I was four. Now I volunteer at the Chinese-American Museum of Chicago. I still stay in touch with my community and support them whenever I can. (As told to Elaine Chen)

Tang’s Garden Restaurant

If you’ve ever found yourself craving Chinese food in Chicago, odds are you’ve ended up at the Cermak-Chinatown Red Line stop. Within sight of the station is an ornate archway that leads into a concentrated plaza of restaurants and shops. Tang’s Garden Restaurant, however, is located half a mile away, just northwest of Chinatown, near Pilsen. The family restaurant, which opened in 2014, is well worth the fifteen-minute walk from the station.

Tang’s unassuming exterior conceals an unexpectedly large and comfortable space within, where red and gold lanterns hang above the bustling wait staff and crowded circular tables. The restaurant’s personal touch is evident in its complimentary treats; each dinner is accompanied by hot tea, meaty soup, and finally, soft tofu pudding. While Tang’s is known for its dim sum, the complimentary dessert is what makes the dining experience remarkable. The sweet pudding, a traditional Chinese snack also known as douhua, is made of soft, warm tofu that melts at the touch of your tongue. A dinner at Tang’s is sure to leave you with a sweet taste lingering in your mouth for the entire trip home—and its memory on your mind until you return. (Abigail Bazin)

Tang’s Garden Restaurant, 1826 S. Canal St. Daily, 9am–11pm. Dessert offered after 4pm. (312) 226-1826

Best 100th Anniversary Celebration

Chinatown Centennial Mural

Located under Metra tracks on the eastern edge of Chinatown, the Chinatown Centennial Mural greets residents, pedestrians, and commuters entering and exiting the neighborhood. Completed last year by professional artists who were assisted by students from the neighborhood, the Mural commemorates the last one hundred years of a thriving Chinese-American community on the Near South Side—and also celebrates the community’s future.

Chinatown’s 100th anniversary occurred in 2012. According to longtime Chinatown resident and historian Susan Lee Moy, around 1911, South Loop-area landlords raised rents, threatening Chinese immigrants that had resettled there from the West Coast. The next year, in what can only be described as a marvel of community organizing, a Chinese merchants’ association purchased fifty-four properties on what is now Cermak Road. (The association bought the buildings through third parties, as Chinese immigrants were barred from owning property.) Much of the Chinese population then moved to Cermak, where Chinatown is today.

The Mural’s three-dimensional dragon immediately catches the eye, but the true intrigue lies in the small circular photographs that line the Mural. On the north side of Archer Avenue, photographs trace the rich, often overlooked history of the area—Chinese families and storefronts from the 1920s and thirties (some of which, like Wentworth Avenue dim sum house and rumored Al Capone hangout Won Kow, are still standing), mahjongg games, the bust of civic leader and park namesake Ping Tom, and generations of local schoolchildren. As the Mural continues south, the photographs depict increasingly recent events up to the present.

With public art such as the Centennial Mural, helped in no small part by the next generation of Chinese-Americans growing up in the neighborhood, the Chinatown community looks forward to its future while ensuring its history is remembered. (Sam Stecklow)

Chinatown Centennial Mural, Archer Avenue between Wentworth Avenue and Clark Street.

Best Youth-For Youth Undertaking

Project: VISION

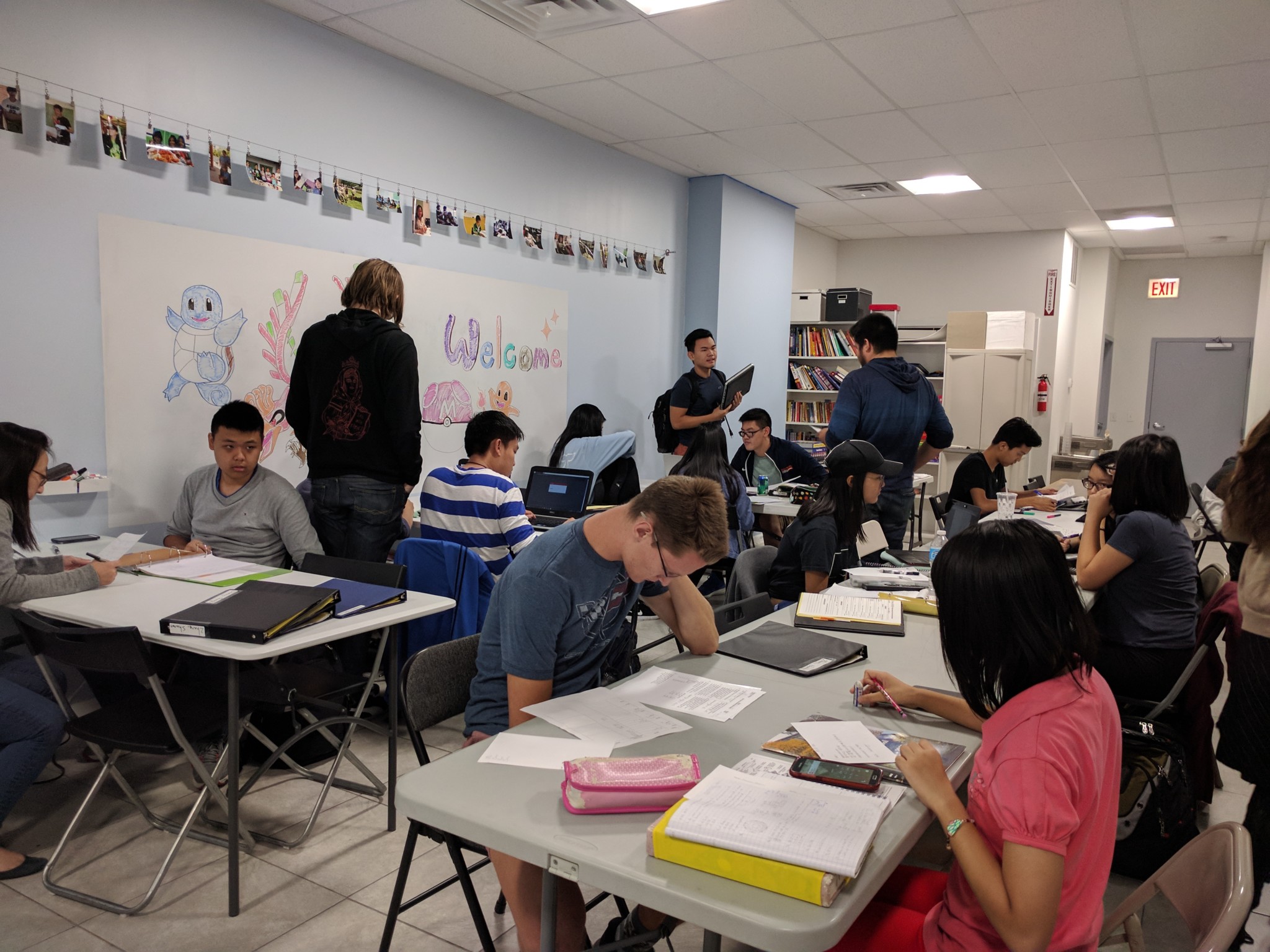

Project: VISION, a nonprofit tutoring center in Chinatown, sets itself against the “model minority” assumption that Asian-American students don’t need academic support. Most of the students at Project: VISION are Chinese American residents of Chinatown and Bridgeport; associate director Sandy Guan said many of them are first-generation immigrants and English language learners. Around seventy percent would be the first in their family to attend college. Project: VISION tutors provide homework help, test prep, and guidance on college applications, as well as helping new immigrant students learn English and navigate American society.

But it’s not all academic—to receive tutoring, students also have to participate in community service and leadership projects. These projects center around helping other youth in their community, like setting up a food pantry, combatting teen substance abuse, and this year, establishing restorative justice programs and helping juvenile delinquents expunge their records when they turn eighteen. Program director Manny Medina said it was this dual emphasis on academics and civic development that drew him to Project: VISION. “We want [students] to come out of Project: VISION with more than just good grades,” he said. “We want them to do service, we want them to learn how to be a leader—and not just a leader, but a service leader.” (Hafsa Razi)

Project: VISION, 236 W. 22nd Pl., unit 1. Mondays–Fridays, 3pm–7pm; Saturdays, 10am–1pm. (312) 808-1898. projectvisionchicago.org

Cermak Road & Canal Street

Walk east along Cermak Road from Canal Street, and you’ll catch a glimpse of one of Chinatown’s many private vegetable gardens. These gardens are dotted throughout the neighborhood on rooftops, backyards, and front porches, featuring a common medley of vegetable plants—Chinese opo squash, tomatoes, chard, bitter melon, and string beans.

In 2014, two University of Illinois researchers scanned the whole of Chicago looking for gardens. Using thousands of high-resolution images and site visits, the researchers found a high density of home-based gardens in Chinatown. The abundance of gardens is likely linked to the popularity of open-air markets in Chinatown, in which gardeners regularly sell their own crops.

This particular garden on Cermak Road, tended by residents of the next-door apartment complex, is bigger and more ambitious than most. It climbs along the side of a train overpass, about fifteen feet in length, with wooden planks roughly constructed into a walkway up the hill. A carpet of squash leaves surrounds makeshift trellises covered in vines. It’s a feast for the eyes, and certainly for someone’s kitchen. (Hafsa Razi)

South side of Cermak Road, east of Canal Street.

Correction 9/28/2017:

A previous version of the interview with Susan Lee Moy misstated her year of birth. It has been updated to reflect that she was born in 1952.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly