On the evening of June 3, a video began circulating on Twitter of a group of men walking around a blocked intersection in Bridgeport. As the armed men, wielding baseball bats, pipes, and other makeshift weaponry, crowded the sidewalks in front of boarded-up businesses on West 31st Street and South Princeton Avenue, concerned residents who felt unsafe called the police, who apparently declined to intervene. That night, several accounts allege that armed men across the greater Bridgeport area harassed, threatened, and chased after people, many of whom were traveling to or from protests occurring in Bronzeville earlier that day.

In the following days, angry residents and one of the armed men in the video met at the office of 11th Ward Alderman Patrick Daley Thompson to air their concerns and frustrations, and the discussion continued on social media. Though a proposed march against vigilantism was canceled a day after the event was created, some are hopeful that a tentative open dialogue about what happened on the night of June 3 will address larger and more difficult issues facing the neighborhood.

The events of the past week recall Bridgeport’s sordid history of vigilantism and violence against people of color, some of which may be unknown or forgotten to the neighborhood’s residents. Many of those supporting the armed men vocally distanced themselves from that history. But while Bridgeport is more racially diverse than it was ten or twenty years ago, the recent tension has highlighted divisions between “old” and “new” Bridgeport, which often fall along geographical and racial lines.

At the heart of the conflict is the contested meaning of safety for Bridgeport residents. The armed men, seeing extensive media coverage of destroyed businesses across Chicago, took to the streets ostensibly in the name of safety.

Many of the people who felt unsafe due to the armed men resolved to call or notify the police. But according to an email from Michael Cummings, the chair of the 11th Ward Independent Political Organization (IPO), residents reported that when they asked nearby Chicago Police Department (CPD) officers to intervene, the officers did nothing to respond to their requests for help. That their concerns seemed to fall on deaf ears raises questions about whether police are able or interested in keeping every Bridgeport resident safe, echoing discussions broached by ongoing international protests, and what the alternatives for those residents could be.

Eric*, a resident of Bridgeport, said that he saw the night’s events unfolding beginning at a local bar on 33rd and Princeton.

“Last night [the bar] was extremely busy because of reopening. There were probably thirty people on the patio,” said Eric. “A lot of those people were the ones who ended up running over to 31st…some of them were carrying bats or sticks and pipes or what-not.”

Later that night, Alex*, another Bridgeport resident, recalled biking past large and unfamiliar pickup trucks patrolling up and down the streets, municipal trash cans barricading alleyways, and vigilantes roaming the neighborhood well past the city’s curfew of 9pm.

Alex reported passing by a group of five or six men wielding bats, who began following Alex as they biked past. When they reached a group of police officers stationed in Armour Square, Alex attempted to report the vigilantes. However, Alex said that the police officer laughed off their concern over the men, and refused to report the incident, stating that it is not illegal to walk down the street carrying a bat.

In recordings of police scanners obtained by the Weekly, when the police dispatcher repeatedly relayed information that there was a group of men with bats around 31st and Princeton, officers described the vigilantes as “neighborhood folks.” In another scanner recording, an officer replies that a group of vigilantes on 47th and Halsted is “neighborhood people just trying to protect the neighborhood.”

At a press conference the next day, Mayor Lori Lightfoot denounced any vigilante activity and denied that CPD was allowing armed vigilantes in Bridgeport. It’s unclear if Lightfoot was simply unaware of the evidence at the time, in which case it’s doubly unclear why she made any claims at all, or if she didn’t consider men wielding bats and pipes to be sufficiently ‘armed.’

A group of concerned 11th Ward citizens presented Thompson with a letter written by resident Ambria Taylor, who had compiled anecdotes of Bridgeport residents experiencing harassment or intimidation from police officers and vigilantes. The letter included allegations that Bridgeport residents were “told directly by the police that people in the neighborhood would be after them” and others “were forced to show their leases by men with baseball bats…to be allowed to pass down 31st.” Another resident said that his “two Black friends coming over to his house…were chased away by [vigilantes] as they tried to approach.” Another resident reported that vigilantes were “drinking openly as they ‘patrolled.’”

Thompson published a post on Facebook acknowledging that “tensions are very high” on the evening of June 3, but the citizens’ letter asked him to publicly condemn the vigilante activity in the neighborhood. Thompson later released a statement in the evening of June 4 saying that he does not condone vigilante violence and intimidation, but gave residents no alternatives to calling the police should they see vigilante activity.

Michael Wagner was one of the armed men at 31st and Princeton on the night of June 3. In an interview with the Weekly, he was adamant that none of the men at that specific intersection were avowed white supremacists (one of the allegations) or actively harassed anybody, though he said he could not speak for the reports of violence in the greater Bridgeport area. He also went to the 11th Ward office the same day other residents dropped off the letter to Thompson. The individuals at the ward’s office all acknowledged that the conversation began as a heated and angry argument, but Wagner ended up apologizing.

“If you guys see a bunch of men on the corner with bats, of course you would be scared. And rightfully so,” said Wagner. “And my point to them was—and not that it’s a good point—you were scared because you’ve never met us and you don’t know us. Granted, that doesn’t make it right…I’m sorry we struck fear, but there was no bad intention behind it besides to keep the neighborhood safe.”

In a public June 5 Facebook post, Wagner detailed his conversation with Chris Kanich, a local resident involved with the Bridgeport Alliance, a neighborhood grassroots organization. “Just spent an hour on the phone with a man who is idk for lack of a better word their lead organizer. Great guy. Ironically he lived on my block my entire life and I never knew,” Wagner wrote. “He has no issues with defending ourselves from anarchists, but to go out and threaten people for no reason is not okay and that’s what they are against. Understandable.”

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

Wagner’s post also suggested that instead of congregating on the streets in large groups, people should only stand armed guard outside their own property. “We are all anti fuckin fascist but the antifa on the media are reckless and should be defended against.” He went on to write, “I urge everybody to stand on your porches, or in front of your own businesses, with bats or what have you, and just hangout and don’t do anything unless something has to be done.” And when discussing the march that at the time was still scheduled for June 7, he wrote that it would most likely be peaceful and residents shouldn’t do anything to stop it, but “IF they did anything it some rogue group showed up, we can be on the scene so fast and beat the shit outta them.”

Wagner’s post received both widespread approval and support, along with some criticism. Many of the positive reactions praised Wagner, who says he often goes by “Wagz,” for helping keep the peace and forging a connection between Bridgeport’s communities. Wagner and a few others hope to get on a Zoom call in the coming weeks and open up a larger discussion about what happened and why people felt the way they did.

Some of his critics felt his apology didn’t go far enough to address the history of racial violence in Bridgeport, and that the people he spoke to didn’t represent everyone angry at the armed men. Wagner and other supporters of the armed men insisted that Bridgeport’s history of vigilantism and white supremacy didn’t define them. As one commenter put it, “Yall are going on facts based on history 40-50 years ago, and that most of those people hightailed their asses out of Bridgeport to the burbs long ago.”

But while some of that history may have had its beginnings more than a hundred years ago, other parts are much more recent, suggesting at the very least that one of the divides in Bridgeport is between those who feel like the neighborhood’s past is firmly behind them, and those for whom it lives on in the present. Whatever the reality of the situation now, reckoning with that past may be part of the neighborhood’s healing process as it addresses the events of the past few days and beyond.

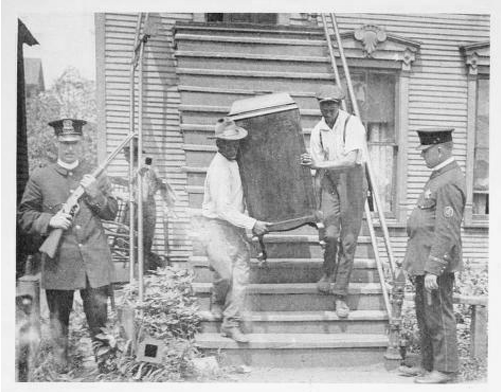

A once staunchly white European immigrant working-class community (and the birthplace of five Chicago mayors since the 1930s), Bridgeport has long held a legacy of racist violence against Black Chicagoans. While Bridgeport was by no means the only neighborhood in Chicago known for this, it was uniquely home to organizations like the Hamburg Athletic Club, which was headquartered at 37th and Emerald and composed of young white men including former Mayor Richard J. Daley. A biography of Daley described the club as “part social circle, part political organization, and part street gang.”

Founded in 1904, the Hamburg, along with similar white “athletic clubs” in the city such as the Ragen’s Colts and Aylwards, “started enforcing imaginary Jim Crow boundaries to stop blacks from encroaching into Irish neighborhoods” as the Black population of Chicago doubled between 1915 and 1940, according to a history published on The Root. Poet Langston Hughes once recalled how after taking a walk past the imagined color line on Wentworth Avenue in 1918, he returned to his home “with black eyes and a swollen jaw, having been beaten up by an unidentified Irish street gang…‘who said they didn’t allow n—— in that neighborhood.’”

The Chicago Commission on Race Relations found these white “athletic clubs” to be responsible for instigating many of the violent attacks against Black Chicagoans before and during the 1919 Chicago Race Riots.

The Commission’s report also found that these athletic clubs had the political pull to “fix” the police department in their favor, allowing them to avoid repercussions for their actions. A member of the Ragen’s Colts reported that the police were “told to lay off on club members,” tipped off club members about heightened police activity, and even rode around in cars to protect club members “in case [they] were picked up.” According to the report, a judge of the municipal court testified to the Commission, “They seemed to think they had a sort of protection which entitled them to go out and assault anybody. When the race riots occurred, it gave them something to satiate the desire to inflict their evil propensities on others.”

Organized efforts at racial violence from white “athletic clubs” like the Hamburg made Bridgeport a dangerous neighborhood for Black Chicagoans throughout the twentieth century. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, the Black population of Bridgeport did not increase above 0.2 percent from the 1930s to the 1960s.

Bridgeport residents employed a number of violent tactics to terrorize Black people and keep them out of the neighborhood. When the Douglas Hotel north of Dearborn Homes burned down in June 1961, eighty of its Black residents were evacuated by the Red Cross to Bridgeport’s Holy Cross Lutheran Church. Upon hearing the news, white residents soon began demanding that the Black fire victims be removed from Bridgeport. The pastor’s wife later recounted that they “threatened to break the windows in the church and screamed obscenities…they threatened to destroy the church if we didn’t get the Negroes out of the building.” In 1964, a white mob threw rocks at an apartment a couple blocks north of the Daley family home that had been rented out to two Black college students. According to Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, the police then “removed the students’ belongings, and told them when they returned from school that they had been evicted.”

Wendell*, who grew up in the now-demolished LeClaire Courts in Archer Heights, recalled how Wentworth Avenue separated Bridgeport from neighboring Black communities. Throughout the late seventies, he frequently went to the old Comiskey Park to catch White Sox games. But throughout his youth, Bridgeport was widely known as a “sundown town” where Black Chicagoans would be in danger after dark.

“There was an old wives tale in the eighties that the cops would kidnap young Black kids and throw them in Bridgeport to finish them off,” said Wendell. “That was something my parents would tell me…it was the boogeyman place where you don’t want to get caught.” This warning rang true—in 1989, the Los Angeles Times reported that a thousand protestors marched in Bridgeport against police brutality, citing an incident in 1988 in which two fourteen-year-old Black boys were arrested at Comiskey Park by police for violating curfew, beaten by the officers, and then “[dropped] off in Canaryville, where they were chased and beaten by a gang of whites.” During the protest, “some of the whites who lined the street shouted profanities or racial slurs…carried the Irish flag and chanted ‘White Power.’”

The two officers involved in the incident were indicted, but similar practices continued citywide throughout at least the 1990s. The 2017 Department of Justice investigation into the CPD found that officers would routinely take young suspects to rival gang neighborhoods, and abandon them there, in order to coerce them into providing information.

In 1997, a thirteen-year-old Black boy named Lenard Clark was attacked and beaten into a coma by three white teenagers as he biked along the border of Bridgeport. The case, extensively detailed in Steve Bogira’s Courtroom 302, was viewed as a bellwether for whether or not white perpetrators of anti-Black violence would face stringent consequences. Bogira also notes the entrenched power structures in Bridgeport—business owners, union leaders, and family with purported mob ties—who lobbied the judge to give the teenagers a lighter sentence. The New York Times reported that “the teenagers later bragged about keeping blacks out of the neighborhood.”

A Tribune article from the same year reported that “the first black family to move into the Bridgeport Homes [a low-rise public housing complex] a few years ago was forced out by egg throwing and harassment.” By 2000, the Black population of Bridgeport had only risen above one percent. The legacy of Bridgeport’s anti-Black violence remains palpable even in recent years; the Black population of Bridgeport has averaged at only 2.5 percent from 2013 to 2017.

The influence of the Hamburg Athletic Club was by no means limited to physical violence in Bridgeport. Instead, it became one of the strongest bastions of the Cook County Democratic Party machine. Former presidents of Hamburg, like former Aldermen Joseph McDonough and Tommy Doyle, and Mayor Richard J. Daley, were able to win local elections thanks to the widespread mobilization of its members. And when Bridgeport-bred mayors controlled the city consecutively from 1933 to 1979, the Chicago Tribune reported that the neighborhood became “Chicago’s political center” thanks to patronage systems that gave Bridgeport residents lucrative jobs with the city. In 1977, the New York Times estimated that “5,000 of the 20,000 patronage workers are from the 11th Ward.”

According to Simon Balto’s Occupied Territory: Policing Black Chicago from Red Summer to Black Power, Bridgeport during Daley’s reign “channeled thousands of police officers onto the CPD’s employment rolls,” including multiple members of the Daley family. These personal connections “‘made it easy for him to overlook the shortcomings of some of its members.’”

Bridgeport is still widely considered to be a police neighborhood. When Paul Bauer, a CPD commander who lived in Bridgeport, was killed in 2018, the streets of the neighborhood were lined with blue ribbons and other memorials. The personal relationships that many generations of white Bridgeport residents have with police officers could explain the police response on June 3. When police officers describe armed vigilantes as “people from the neighborhood,” they may mean, quite literally, their neighbors or family.

Bridgeport is more racially diverse than ever; the neighborhood is now majority minority, with 63 percent identifying as either Latinx or Asian. It’s changing in other ways, too—the median house price rose 9.9 percent in 2019 (double the city’s increase of 4.8 percent)—and worries that gentrification is on its way are common. When Johnny O’s—which at various points in its history served as a neighborhood bar, restaurant, and more recently, convenience store and hot dog stand—closed its doors last year, neighborhood residents, recent and established, mourned the loss of a working-class institution. “Johnny O’s was old school. It added character,” said one lifelong resident.

But change doesn’t come without opposition, or happen all at once. Even in recent years, the persistence of vigilantism, racial hostility, and conflicts around police protests remains a reality in Bridgeport. In 2012, a protest against police brutality in Bridgeport ended with a public “shouting match” and a scuffle between a neighborhood resident and a protestor, according to NBC Chicago. In 2015, DNAinfo reported on Bridgeport men who acted as the “Neighborhood Watch.” According to the article, the three (unarmed) men drove around the neighborhood at night and reported burglaries, suspected gang activity, and broken street lights to the police, many of whom recognized the men as local vigilantes. The same year, two Bridgeport rallies were set for the same day—one in support of CPD and one against police misconduct. Both were canceled.

Amanda’s* family, which is Chinese-American, has lived in Bridgeport for three generations. While growing up, she and her family have also experienced the neighborhood’s hostility against Chinese immigrants who were moving outside of Chinatown and Armour Square towards Bridgeport.

“The first time I was ever racialized was around the intersection of where the video happened…it was the first time I was called a racial slur by a white child around my age,” said Amanda. “My sister was chased by two white boys on bikes while she was walking home with her friend, who was also Asian-American.”

Still, Amanda notes that there are local organizations in Bridgeport, like the Bridgeport Alliance, that are doing valuable work to support the neighborhood’s residents of color. But she still feels as if there’s an “indirect silencing of people of color [because of] the fear of racialized violence.”

The events of the past few days have only further cemented that Bridgeport’s residents of color are still confronted with the neighborhood’s past. But it’s less clear what the neighborhood can do to address those issues and ensure that every one of its residents feel safe.

In response to the vigilantes, some local residents cobbled together a counterprotest scheduled for June 7. But even the Facebook page of the event is full of controversy, with some people expressing concerns about retaliation and intimidation against Black and brown protestors and the protest’s lack of communication with Black organizing groups. Other comments came from disapproving Bridgeport residents who thought more residents should be thankful for the vigilantes. Eventually, the protest was canceled due to safety concerns.

“Over the course of the last couple days, lots of people have been calling for protests, but people who know the realities on the ground in Bridgeport today, and its history when it comes to clashes between white people and nonwhite people, are kind of recognizing that you can’t just say you’re going to stage a protest without doing your due diligence to make sure people who attend can have a reasonable expectation of safety,” said Chris Kanich, who is involved with the Bridgeport Alliance and a co-leader of the Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid organization. “You have a high onus to make sure people stay safe. Bridgeport feels like a tinderbox right now.”

Pastor Nic, who has been working at First Lutheran Church of the Trinity since 2019, said she has never felt hostility or disrespect from the people in her ministry, but agreed that the neighborhood remains a flashpoint for conflict for many people of color.

“It’s complicated and it’s difficult because there are bits of hope I see in Bridgeport,” she said in an interview with the Weekly. “And then while we’re having a conversation with Alderman Thompson I see police circling the block eight times. Eight times for a thirty or forty minute conversation….I stress that because it reinforces why this action had happened. We are being overpoliced. If we are going to rely on cops to do the work of protecting and serving, rather than circling around and trying to get a sense of what concerned constituents are doing with the alderman, they should be out making sure people are not taking the law into their own hands.”

Many of the residents’ disappointment with the unwillingness or inability of the police to make them feel safe comes as protests across the world question the role of police in public safety, and ask people to reimagine what it would take to keep communities safe. But since people taking up arms and patrolling the streets themselves doesn’t appear to be a good answer, it raises the possibility that neighborhood residents may need to come together and figure it out themselves.

“[When I saw] vigilantes targeting people who look like me, in my experience, that was the first time I was actually afraid to be in my neighborhood, to be in Bridgeport,” she continued. “But what was inspiring and hopeful was that without even asking, community members and parishioners said that they were going to come by the church on Tuesday. They’re recognizing that there is potential for something to happen, especially since we are on 31st Street. People showed up. That in itself was a redemptive peace for me in my experience and relationship with Bridgeport.”

“Although these might not be all lifetime Bridgeport residence [sic], they love this neighborhood and want it to be safe for all,” Wagner wrote in his post. “I realize some stubbornness here and I know a few will read this and blow me off and think I’m a ‘sellout,’ but know I am doing this and talking to strangers and going to ward offices, for you. For us. Because already Bridgeport has gotten too much negative attention, and wrongfully so.”

“There is a consensus…that we all want to live in a safe neighborhood, and we all want to have a safe place to have businesses, and we all want to thrive as a community,” said Amanda. “I don’t know how or what that would look like. That’s where I’m kind of struggling with…I think it’s unearthing a lot of things that were never really addressed or talked about within the community.”

Numerous interviewees requested their names to be changed or for their last names to be withheld for the concern of their own safety.

Rachel Kim is a senior editor. She last wrote about the Gage Park High School fifty year Black students reunion.

Non-fiction Creative writing at best. When in Rome, do what the Romans do or dance to France.

Bridgeport and all predominant CPD are still very racist and people who stir the pots are just spineless cowards