As a main building at the University of Chicago Law School, the Glen A. Lloyd Auditorium is usually packed exclusively with academics and law students. But during the Youth/Police Conference, it wasn’t scholars who did most of the speaking. Rather, it was teenagers, youth workers, police chiefs, activists, additional community members, and parents who were eager to share their lived experiences.

The conference was a two-day gathering on April 24 and 25 aimed at stimulating dialogue about interactions between youth and police as part of the four-year old Youth/Police Project, a collaboration between the Invisible Institute, participants in Hyde Park Academy’s Media Program, and the University of Chicago Law School Mandel Clinic. The initiative seeks to create a dialogue between minority youth and future lawyers about the relationship between the law and the people whom it’s meant to serve, with an emphasis on how that relationship can be improved. “We want to build, first and foremost, from all that we’ve learned from the kids,” said one of the panelists early on in the conference, distilling the goal of the conference and the larger project.

At the beginning of the conference, event organizer Jamie Kalven of the Invisible Institute made it clear that “this will not be a traditional academic conference.” Five sets of panelists, including professors (from Stanford, the UofC, and Columbia), former and current police officers, and activists, all spoke to their knowledge of police interactions with community youth, but each panel began with recordings of students who told stories about their perceptions of and interactions with police. Hyde Park Academy students were seated in the audience, pulled out of school for the day to see the fruits of their work with the Institute.

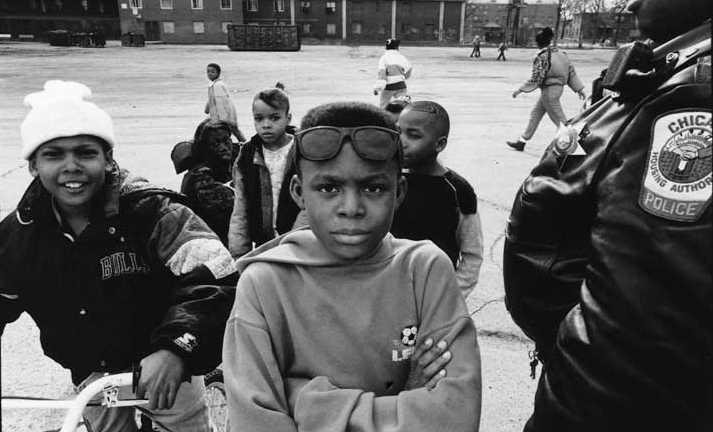

The two panels on the first day of the conference, entitled “How Youth See Police. How Police See Youth” and “How it Makes Me Feel—Youth,” sought to bring usually neglected community and youth voices to the oft-misunderstood way that African-American children engage with the police. Topics included lack of neighborhood knowledge (“if only the police had knowledge of neighborhoods that the kids have!”), the normalization of mistreatment, and a tendency towards internal problem-solving (gangs, family members, etc.) rather than turning to a police force that none of the community members trust.

When the panelists addressed audience questions, the scope of the conference broadened to cover a wider range of topics, including police brutality, the economic underpinnings of the modern prison system, and 21st-century racial segregation. Near the end of the program, a man took the floor to describe his belief that American society at its core was informed by ideals of slavery, now executed through the prison-industrial complex. His statements, placing the conference within a larger context, were referred to repeatedly throughout the rest of the panels.

The second panel, “How it Makes Me Feel—Youth,” focused on the psychological state of African-American students, adolescence, and the appropriate approach for police to take with teenagers. Concerned parents spoke up, expressing their concern about the too-often assumed criminality of their children. Margaret Beale Spencer, Urban Education professor at the UofC, whose research focuses directly on adolescence and the impact of race and culture on development, took the opportunity to draw attention to the hindrances that such animosity can cause in mental development. Youth Mentor and Blackstone Bicycle Works instructor Jamel Triggs offered advice on how police might better inhabit the roles of role models and mentors, rather than enemies.

The Youth/Police Conference attempted to guide listeners and participants toward possible solutions and nuanced discussions. But while each of the panels brought varied perspectives together, what may have been the most valuable part of the conference was the lunch break, when community members and burgeoning academics and lawyers alike could (and did) sit down and talk to each other, all of them eager to repair what sometimes seems like a broken relationship.