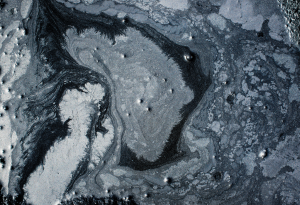

Spring finally came to Chicago about a month ago, turning the lake from gray to blue and exposing endless lawns of dead grass. On the Southeast Side, along the banks of the Calumet River, the warmer weather slowly turned several large hills from snow white to a metallic black. The hills are made entirely of petroleum coke, a byproduct of refining crude oil.

The debate around how and where petcoke should be stored has snowballed since December, when British Petroleum’s refinery in Whiting, Indiana completed a $3.8 billion renovation, which included a state-of-the-art coker that will triple its output of petroleum coke.

The petcoke from Whiting is currently being stored at two terminals on the Calumet River, about one mile from the border with Indiana. Both of these facilities are owned by KCBX, a subsidiary of Koch Industries, which has an exclusive contract with BP for storing the company’s petroleum coke. (A third storage site in the area is owned by Beemsterboer Slag Corporation, which was storing petcoke without the proper permits up until November of last year, when the city forced them to remove their stockpiles.)

Though the petcoke is enclosed in a pit with forty-foot walls when it’s on BP’s land in Indiana waiting to be placed on a barge and sailed to Illinois, it is left open to the elements during transportation and storage. It sits uncovered just hundreds of feet from houses, and only blocks away from schools and hospitals.

Last July, a video of a particularly windy evening in Detroit showed a formidable cloud of what looks like ash from a fireplace. It was in fact petroleum coke dust, blowing over the Detroit River. Then, in August, there was a windstorm on the Southeast Side that lifted a cloud of petcoke from its holding grounds on East 100th and East 106th Streets, blowing it across the neighborhood.

Since then, both Governor Pat Quinn and Mayor Rahm Emanuel have proposed regulations on the storage of petcoke, and Lisa Madigan, attorney general of Illinois, has filed lawsuits against both KCBX and Beemsterboer for violating dumping regulations.

Chicago is no stranger to the hazards of being an industrial town, and residents of the Southeast Side have lived with the more pervasive realities of industry for over a century. Petcoke is the latest iteration of this struggle: another chapter of confusion, ignorance, and inconsistent government action.

The wind that blows along Lake Michigan’s shores certainly does not stop for byproducts of oil refining, and residents of the Southeast Side have been facing the almost non-stop dispersal of stray dust from the faces of the black hills for over eighty years. Whether it’s hills of petcoke or coal dust, relief only comes when it snows.

There’s a lot of people who don’t know the difference between Diet Coke and petcoke,” says Tom Wolf, executive director of the Illinois Chamber of Commerce’s Energy Council. It’s a good line, and not untrue.

Petcoke comes in two varieties, green and cooked. Green petcoke is the material that is transported from Whiting to the terminals on the Calumet River. When that material is burned to make things like processed aluminum and cement, it’s declared cooked. Many factories around the country use petcoke of either variety in small amounts.

It is consumed at the highest rates by aluminum smelting plants and by factories that produce bricks. Most of the United States’ petcoke output is sent overseas, however—typically to places like Japan, India and China, where regulations on pollution are not as stringent. In the first quarter of 2012, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, those three countries accounted for over a third of U.S. petcoke exports.

In the early part of the twentieth century, petcoke was considered a waste product from the fuel-refining process. But since the thirties, petroleum coke has been burned as a secondary fuel that can be yielded by refining crude oil in a certain manner. It is most analogous to steam coal in function, yet it can contain as much as ten times more sulfur and release over fifty percent more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Unlike coal, petcoke burns without producing much ash—between four and nineteen percent less, according to the American Fuel and Petrochemicals Manufacturers. This makes it a convenient energy source for Third World countries, which are less likely to have sophisticated waste management systems.

What makes petcoke so popular around the world, however, is that American producers consistently and significantly discount the price: it generally gets a twenty-five percent mark-off relative to coal, according to a report from Oil Change International. It is, as they say, priced to move.

In 2011, the U.S. produced close to sixty-two million tons of petcoke, and almost forty million tons of that was exported, according to a report from Roskill. The report estimates current global production at one hundred million metric tons each year, and predicts that the world will produce 170 million metric tons in 2016.

Nearly every manufacturing process has its byproducts, but petroleum coke, or petcoke, is also a byproduct of the present moment in climate policy. As more and more oil flows south from Canada—and with the possible introduction of hundreds of thousands more barrels each day with the completion of the Keystone XL pipeline’s fourth phase—the output of petcoke from the nation’s refineries has doubled since 1999, to 180,000 tons a day, according to the same report from Oil Change International.

Canada’s bituminous sands, in Alberta, produce oil that is called dark, or sour, in the petroleum industry. Formed in the Cretaceous Period, between 140 and 60 million years ago, the sands have been estimated to hold about 169 billion retrievable barrels, which amounts to just nine percent of the total barrels of bitumen estimated to lie below the boreal forest.

The sands are second only to the Arabian Peninsula in petroleum reserves, though the liquid they produce is a mixture of petroleum, sand, and water, and is harder and more costly to refine than oil that comes from either Saudi Arabia or Texas. According to the report from Oil Change International, processing oil that is heavily laden with bitumen yields double the amount of petcoke obtained from refining light oil.

BP’s multi-billion dollar upgrade includes a new distillation unit to help the plant process more of this unconventional oil. With its new machines, the refinery in Whiting is set to become the biggest producer of petroleum coke on the continent.

Like a lot of things that come from the belly of the earth, petcoke can be potentially harmful, especially in smaller sizes.

Petcoke is what is called particulate matter, or PM. World environmental organizations measure the size of particles in micrometers, and classify different particles as either PM-10 or PM-2.5. A particle that is PM-10 is less than ten micrometers in diameter and smaller than a human hair. A particle that is PM-2.5 is less than two-and-a-half micrometers in diameter and is small enough to wend its way into the deepest part of your lungs.

An ideal yield of petcoke produces balls a bit smaller than a pencil eraser, but in transit and storage those pellets can break down and become PM-10 and even PM-2.5 dust, smaller than the particles in an aerosol inhaler.

Sarah Lovinger, executive director of the Chicago chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility, says that PM-10 dust can exacerbate existing lung conditions like asthma and emphysema, and that studies have linked fine particulate matter to lung cancer.

The EPA, however, classifies petcoke as a “non-hazardous material.” It has done studies since the nineties on the possible adverse effects of petcoke on rats, monkeys, and plants, and has found negligible toxicity in plants and no cancer in the animals. Unlike other infamous particles, such as asbestos or silica crystals, petcoke was found to have no effect on the genetic makeup of the rats or monkeys—it didn’t change the order or appearance of any of their chromosomes or genes.

The EPA acknowledges readily on its website that particulate matter has been linked for years with lung damage, and their studies found as much. A report from June 2011 references a two-year inhalation study published in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine in 1987 that “produced irreversible respiratory effects…in rats and primates (both sexes) at all concentrations tested.” The animals developed lesions and cysts, as well as scarring and a build of a fibrous tissue around the openings to the lungs.

Unfortunately, studies on animals in a lab can often have little bearing in determining a substance’s potential threats toward humans.

“You can’t tease out the different environmental factors [with animal studies],” Lovinger says. These studies point to a general conclusion, but they can seldom link widespread health issues, such as asthma, to single causes. When people who live around industrial areas get sick, researchers have to deal with a host of gases, particles, and other products that could be dangerous at varying levels and in various combinations.

“We certainly know, from studies that have been done here, in the Seattle area, in Toronto, and in other places around the world—they’ve looked at this in Italy, and in London, in Brazil—that if you live in certain areas there seems to be a higher prevalence of asthma,” says Louise Giles, medical director of respiratory therapy at Comer Children’s Hospital. “We know that asthma rates in Chicago are higher than the national norm, and we know that it’s a real problem.”

“Petroleum coke in and of itself, as long as its not airborne, is probably not toxic,” Giles adds. “But the minute it becomes airborne it’s an inhalant—bang, there you’ve got your issue.”

Tom Shepherd, president of the Southeast Environmental Taskforce, or SETA, told me about the role the dust plays in the everyday lives of people living around the piles of petcoke.

“Just on a typical day, with the wind as it is today, you can feel it if you’re standing there,” he said. We were sitting in SETA’s offices, at 133rd and Baltimore Avenue. “You know it’s there. You may not see every speck, but if you feel it you know it’s there. You’re gonna feel burning in your throat and in your nostrils. It’s there—it’s obvious. It’s like an invisible killer.”

SETA is a volunteer-run, grass-roots organization that focuses on educating the Southeast Chicago community on local environmental issues and sustainable development. It operates on funds from members, both residents and area businesses.

“We have a high rate of asthma,” added Peggy Salazar, SETA’s executive director. “We know that. We have a high rate of cancer here. Something in this area is causing that. What’s different about our area? We’re industrial. So we put two and two together. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that’s what’s different about our area.”

A study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, published in 2008 by doctors from Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, contains a map of Chicago’s child asthma rate by neighborhood. Southeast Chicago is colored green, falling into the five-to-twelve percent prevalence range—right around the national average.

Areas closer to the Dan Ryan highway have much higher rates—upward of thirty percent—and are yellow and dark red. A 2012 report from the Centers for Disease Control found the average rate of asthma in children in the U.S. to be nine percent. No studies have been done on neighborhood asthma rates in Chicago since 2008.

SETA’s offices are just ten minutes down Avenue O from KCBX’s terminals on 100th Street. Running parallel with the state border, Avenue O is about half residential, half industrial, with the section between 117th and 130th Streets flanked by warehouses and industrial storage lots. Its northern side ends in a large warehouse facility on the banks of the Calumet River.

About halfway in between is George Washington High School, with an enrollment of over 1,500 students, ninety percent from low-income families. On the school’s roof is an air quality monitor controlled by the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency. In 2012, the monitor logged the highest twenty-four-hour average of PM-10 in the state for that year: two-thirds the acceptable limit of airborne particulate matter by EPA standards.

For 2014, the Washington High air monitor was supposed to be decommissioned. According to an Illinois EPA spokeswoman, that decision was reversed after the agency’s 2014 report came out. It is one of only four PM-10 monitors in the state; the second closest one to the Calumet River is in La Grange.

Other schools in the area have been feeling the presence of the petcoke, but in different ways. In January, at the St. Simeon Serbian Church on 114th Street, a community meeting was held that drew over 150 residents, journalists, and employees of KCBX and the Illinois Chamber of Commerce. One of the many community members to stand up and address the crowd was Nick Limbeck, a second-grade teacher at Gallistel Language Academy at 104th Street and Ewing Avenue, who talked about the presence of petcoke in his classroom.

“Mainly the black dust accumulates on surfaces around the classroom, on tables, chairs, desks, things like that,” he told me. “It was most noticeable during the warmer months. It was not as noticeable the last few months.”

From his third-floor classroom, the piles in the KCBX terminal are readily visible. Limbeck had his students conduct a small “study” of the black dust, having them wipe wet paper towels on the windowsills and make observations and drawings of the substance.

Two students in his class of twenty-six have asthma, and both students were forced to miss more than a week of class at the beginning of the school year. Limbeck says their parents were sure the absences stemmed from petcoke inhalation.

He told me he was disappointed with the way the city has dealt with the petcoke issue. “I feel like I’m in a George Orwell novel, where fixing the problem is increasing it,” he said.

After the meeting at St. Simeon, I talked with Brian Urbaszewski, director of environmental health programs at Chicago’s Respiratory Health Association. He thinks the petcoke should go completely.

“The only safe limit is zero,” he said, pointing to a positive, linear relationship between general pollution and health issues.

Dr. Giles agrees, and added that the issue of pollution is even starker for children. “We know that particulate matter is a kind of airborne pollution,” she said. “The younger you are, the more susceptible you are to damage that can happen from prolonged inhalation.”

When I talked to Tom Wolf, of the Illinois Chamber of Commerce, he expressed concern that residents were blaming petcoke indiscriminately for the area’s perceived health problems.

“That’s an industrial area down there,” he said. “It’s a huge assumption to say one facility is causing all those perceived problems.”

In the same year that Washington High School’s air monitor saw record levels of PM-10, it also recorded the highest yearlong averages of cadmium and nickel in the state, though nowhere near the EPA’s limits. Coal dust, which has been stored along the Calumet River for over eighty years, looks very similar to petcoke when it is stored in piles or is airborne, or when it clings to the siding, windows, or front steps of a house.

“What I’m worried about happening is you do knee-jerk reaction regulations, you put a company out of business or make it spend hundreds of millions of dollars, and at the end of all that the community still has dangerous levels of particulate matter because the problem’s from someplace else,” Wolf continued. “I’ve seen people tell me, I’ve seen people throw up filters, but anecdotal evidence isn’t science.”

The filters Wolf mentions are those found in your average in-home air-treatment system. At the meeting in January, one of those filters was held up in front of the crowd by Peggy Salazar, of SETA. It had only lasted a few weeks the previous summer before turning the color of a charcoal briquette.

“That’s not normal,” she said, as she swept her fingers across the filter and held them up, showing a black residue one usually sees on the hands of coal miners. The filters were from 109th and Mackinaw, about two blocks from a petcoke storage area.

“If I had an air filter like that I would be pretty mad,” Wolf said when I mentioned Salazar’s presentation. “But I would also like to think that I would ask the city to determine where that is coming from, and not assume that I know where it’s coming from.”

Salazar says that she contacted the Illinois EPA to have the filter tested, to see if it was in fact covered in petroleum coke dust. The Illinois EPA, she claims, refused to test it.

“We were a little hesitant to just come out and call it petcoke,” she says. “I can’t imagine it being anything else, either. Even if its coal dust, it’s still an issue.”

Given that petroleum coke has been stored along the Calumet River in varying amounts for over two decades, the city’s recent actions do seem a bit sudden. Beemsterboer Slag Corporation was ordered to get rid of its petcoke after the Illinois EPA discovered the company had started handling the substance on its twenty-two acre facility before they had received the necessary permits. The company’s piles were gone within a month.

When Governor Pat Quinn spoke up about petcoke in January, he announced proposals that were coming from his office that he hoped would be ratified by the Illinois Pollution Control Board, a non-governmental agency that reviews regulations and legislation pertaining to the environment. The city had a slightly longer timeline to develop rules with regulators, stretching from February until last week.

“That’s still fast,” Tom Wolf said of the city’s regulations. “But if you’re giving me a comparison, that’s better than seven days. And ultimately I believe the city was responding to a specific issue and protecting their citizens.”

Quinn’s regulations were voted down by the Illinois Pollution Control Board, and the city’s deliberated response came Tuesday, April 1, at a meeting of the zoning committee that concerned the ordinances around petcoke. Though a ban on petcoke within the city-limits of Chicago had been championed by Aldermen John Pope (10th) and Ed Burke (14th), Pope, who represents the entire Southeast Side, presented a revised version that would make storage of petcoke permissible if it is at a facility that also cooks the petcoke to fuel a manufacturing process.

An outright ban, Pope argued, would make the city legally vulnerable to a court challenge by KCBX and their parent company, Koch Industries. Pope asked the committee to defer its decision until later this month, saying, “I think there may be a few more items we can add.”

This week, hours after this issue goes to print, the zoning committee is set to give what many think will be the final set of ordinances concerning who is allowed to store petcoke and how in Chicago. It’s taken since January for the committee to come up with a final decision, but Salazar has low expectations.

The question of enclosure to prevent the wind from sweeping the petcoke up and drifting it onto the homes of the Southeast Side was answered last month, when the Chicago Department of Public Health announced that any petcoke storage facility needed to make plans to fully enclose its piles within ninety days, and erect the necessary structures within two years.

However, questions still remain over the continued impact of the piles on the community and the environment. The studies done on plants and animals showed evidence that petroleum coke, when inhaled at high concentrations over long periods of time, can cause serious, largely incurable lung damage, but some residents are concerned about what could happen if petcoke got into their water supply through drainage issues or some kind of leak.

The lawsuit filed against KCBX by Lisa Madigan in early March contends that KCBX has shown disregard for water pollution standards, and that the concrete walkway between the water and the piles of coal dust and petcoke is too narrow to prevent the dust from seeping into the Calumet River and into the water supply of the area. A press release from Madigan’s office says that an inspection by the Illinois EPA found many deep cracks in the walkway through which the petcoke could have seeped into the ground and water.

The rolling hills of black dust along the Calumet River have been fixtures of the neighborhood for over two decades. Yet, as BP starts to process crude oil at triple its previous capacity, the role of petcoke in the ongoing metropolitan drama has become much more important, not just to residents but to those with a stake in the industry.

When I talked to Peggy Salazar of SETA recently, she expressed her deep disappointment at the way the city has handled the regulatory process.

“They came out with guns blazing, like it was high noon or something,” she said. “Okay, you put some regulations in place, but who’s going to enforce them? What’s changed, really? What’s going to happen?”

She worried that the setbacks in City Hall would discourage residents of the Southeast Side from getting organized against KCBX. “Their experience is going to be that nothing changes,” she said.

“We live in a modern society,” Tom Wolf says. “I take the El, I drive a car. There’s no perfect, nonpolluting way of living.”

Last Saturday, the Southeast Environmental Taskforce hosted a march from State Line Avenue to the petcoke piles on 108th and Buffalo. Over one hundred people showed up, double what Peggy Salazar had anticipated.

“If we got fifty we were going to be really happy, so we were twice as happy,” she says.

This week, the zoning committee is set to give what many think will be the final set of ordinances concerning petcoke in Chicago. It’s taken since January for the committee to come up with a final decision, but Salazar has low expectations.

“We’re not satisfied with what they’re giving. They need to enclose the piles tomorrow, not two years from now,” she told me. “We’re still disgusted and fed up, because it seems like were not gonna get what we want. But we’re not going to give up. As long as people are showing their support, like they did on Saturday, the effort is not going to die.”

Note: On Wednesday, April 30, the City Council approved the ordinances presented at the beginning of April. The ordinances limit further expansion of existing petcoke storage areas, and make it impossible for other companies to establish new storage terminals. KCBX will be forced to keep its petcoke stocks at a certain point, and to give the city quarterly updates on how much is being stored along the Calumet. Universal Cement, which is looking to expand its factory at 117th Street and Torrence Avenue, will be allowed to store petroleum coke for use in its manufacturing processes. In three years, the commissioner of the Chicago Department of Planning and Development will submit a report to the City Council on whether to impose further limitations on the storage of materials that may pose a threat to public health.

Fantastic items from you, man. I’ve take into account your

stuff prior to and you are simply extremely fantastic.

I really like what you’ve bought here, certainly like what you’re stating and the way through which you assert it.

You are making it entertaining and you continue to take care of to

stay it smart. I cant wait to read much more from you.

This is actually a great site.