One of my uncle’s friends who is my friend too asked us to give him a kiss to the cheek…When I tried to do it, he turned his head and I kissed him on the lips instead of the cheek. That’s when I learned not to trust everyone.” Cung Lieu wrote this reply to Krystal Nambo after she asked him to share about a crazy memory he had.

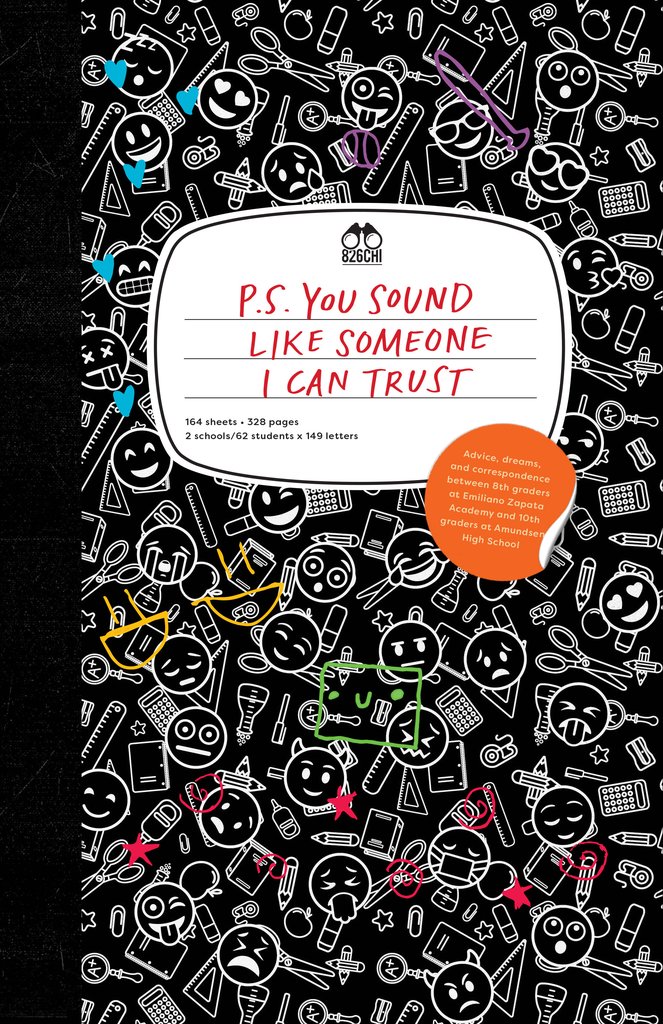

Vanessa Cruz also wrote about trust. At the end of her first letter to Jazmine Rodriguez, she added: “P.S. By the way, Jazmine, you sound like a person I can trust.” This piercingly candid line ended up inspiring the title of the newest book published by youth writing nonprofit 826CHI, P.S. You Sound Like Someone I Can Trust.

826CHI, the local chapter of 826 National, fosters the writing skills of students ages six to eighteen through tutoring and workshops. As part of its Young Author’s Book Project, 826CHI coordinated a series of letter exchanges between eighth graders at Emiliano Zapata Academy in Little Village and tenth graders at Amundsen High School in Ravenswood. The organization paired students based on their answers to a survey asking about interests and hobbies, and then met up with the students once a week throughout the school year to workshop the letters. The product is a collection of twenty-nine pairs of letter exchanges.

Flipping through the pages, seeing only the words written by each student, the occasional doodles dotting the margins, feels similar to how the students must have felt when receiving the letters—consuming every bit of information about unfamiliar and faceless individuals—until the end of each exchange reveals pictures and biographies of the students involved.

The letters, in their youthful bluntness, are refreshingly amusing: “I’m going to ask you only five questions since this is the last letter,” writes one student. Two questions later: “Okay, I know I said that I was going to ask you five questions, but my head is out of questions.”

The candor is at times shocking—the students’ word choices wonderfully conveying the complexities in their minds. “The first thing I remember remembering is my friend Jasmin. She died when I was in sixth grade,” one student wrote.

Another student, responding to an 826CHI writing prompt asking what hope is, answered, “The word hope to me is honestly just a word… My dad was desperate to stick by my side and be there for me as he was getting sicker. So, he hoped and prayed he’d get better, yet that got him nowhere. He hoped, but I guess it just wasn’t good enough.”

Maria Villarreal, Director of Programs at 826CHI, said that the mode of letter-writing prompted this openness. When 826CHI visited the students’ classrooms, its members organized activities in which they asked students, “Who are you?” The members tried to encourage the students to look at drafts of their letters and ask themselves, “Is this true of who you are?” By asking this of the students, the organizers pushed them to reflect further on their work and thoughts, allowing them to express themselves more easily to others.

Many students bonded over common music or reading interests, but of course the most memorable exchanges were those in which the students exposed their most vulnerable selves. Jazmine Rodriguez, one of the Amundsen tenth-graders, now interns at 826CHI after she met Villarreal through this project. Her exchange with Vanessa, the Zapata eighth-grader whose postscript gave the book its name, yielded an intimate and enriching relationship between the two.

The two have learned from one another in unexpected ways, with Rodriguez and Cruz often sharing and receiving advice from one another. After seeing Cruz postscript at the end of the first letter, Rodriguez explained she “teared up a little bit.” Seeing how open Cruz was, Rodriguez thought, “You know what, let me put my guard down and tell her something about my personal life that I don’t normally tell people.” She opened-up about her father who abandoned her family, explaining that detail as “a dead rose in my heart.” And in her last letter to Cruz, Rodriguez wrote: “I wish someone would’ve told me this: be wise and always be as humble as you are now.”

While Rodriguez gave Cruz seasoned advice, Cruz incited Rodriguez to abandon barriers. “That’s one thing Vanessa did for me,” Rodriguez recalled. “Sometimes I would walk in on a Tuesday being like I really don’t wanna be doing this, but when I would sit down and space away from all my friends and not get distracted and actually wrote, amazing things happened from that.”

What Cruz did for Rodriguez, the students did for me. Reading through these honest stories, making me smile and sigh and pause, I was transported back to days where I don’t remember stopping myself before opening my mouth or replaying what I had just said after the words had escaped.

The honesty of the students provokes questioning the boundaries we put up between ourselves and the world—boundaries that affect how we present ourselves to others, but, more importantly, how we see others.

The students’ accounts add authentic perspectives to and challenge the narratives that people often hear about Chicago Public Schools (CPS). CPS has been called a failing school district, its students accused of lagging behind the “average” student (although in fact, CPS students score higher on standardized tests than comparable students statewide). People often hear about Chicago schools and students in a negative light, said Eric Markowitz, one of the Amundsen students’ teachers for the project. The students have challenged this narrative in creating “such an entertaining and great book like this.” He would be surprised “if [people’s] opinions don’t change into something positive” after reading the book.

“These kids are CPS kids,” said Tanya Nguyen, the Amundsen students’ English teacher. “They have different experiences and challenges and even triumphs than kids that are in different districts.”

The letters don’t let you forget this. One student from Amundsen talks about “dodging bullets on a day-to-day basis in [their] neighborhood,” explaining it is like “playing a survival game.” Another student from Zapata writes in a different exchange, “In my neighborhood at 7 am it is quiet and normal. But at 7 pm it’s dark outside, the street lights don’t work, and you can hear cars firing because they go too fast on speed bumps. Where I live, there is also lots of killing.”

However, the students also share anecdotes about kissing mishaps and the trust they feel for their friends. Regardless of the challenge, the student’s writing sets them apart from the stereotypes of the CPS label. As Nguyen said, what’s “really powerful” is that “there is this publication that celebrates all of these things that make our kids unique and special and strong.”

The letters also challenge broader narratives of residents in Latinx communities. “Students of color, students that are part of an immigrant community…have been vilified in different ways this year in the political climate that we’re in,” Eliza Ramirez, the Zapata students’ English language arts and writing teacher, said. The letters’ publication is so important, Ramirez said, because the students “got this chance to tell their stories and to talk about who they are.”

When recognition across shared humanity occurs, like Rodriguez had said of the writing process, “amazing things” can happen. The letters foster this recognition in the book’s readers, but also, in the first place, in the students who wrote the letters, who live in two different neighborhoods fourteen miles apart. Ultimately, the importance of the publication traces back to these students.

Rodriguez and Cruz, for example, sustained their exchanges after the project ended. At the book’s launch event, many students were shy to talk to their letter partners, as it was the first time they were allowed to meet. “It was hilarious,” Villarreal said, like a middle school dance except with eighth graders on one side and tenth graders on the other. Yet, when Rodriguez saw Cruz, “I just gave her a huge hug, I was like, ‘Hi! I’ve been waiting to meet you for so long.’”

Afterwards, they exchanged phone numbers. According to Rodriguez, some other students also connected on social media. Rodriguez promised Cruz that she would respond quickly, not “in three weeks,” which is how long the letters often took to be exchanged. “I told her: ‘I’m always here for you…. You can always count on me.’”

What she told Cruz in her last letter seems to be truly lasting: “P.S. You’ll always be my best friend.”

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.