Chicago Public Schools’ perennial funding woes have occupied headlines since time immemorial, but recently, the bad news seems to be increasing in both quantity and severity. Recently, Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Forrest Claypool, his CPS CEO, were forced to walk back statements that CPS schools would close weeks early if the state did not provide more money after a judge threw out their last-ditch lawsuit claiming the state’s public school formula is racially discriminatory. CPS was forced to take out a $389 million high-interest loan to keep schools open, which some aldermen compared to a “payday loan” and does not even entirely fill the budget gap. On top of that, the district is attempting to wring another $467 million it says the state owes it to make its pension payment next month, facing yet another bond rating downgrade if it does not make the payment.

Mayoral and CPS officials put much, if not all, of the blame for the district’s disastrous finances on Governor Rauner’s budget stalemate with Democrats in the General Assembly. For Stephanie Farmer, an Associate Professor of Sociology at Roosevelt University, however, there’s another place to look within CPS itself when considering the causes of the district’s crises—charter schools.

In a study co-written with Ph.D candidates at Loyola University and the University of Illinois at Chicago and published last month in partnership with the Project for Middle Class Renewal, Farmer examined the relationship between public school closures and charter expansion between 2000 and 2015. The study suggests that the CPS charter policy, or lack thereof, is partially responsible for the current budget crisis. Furthermore, its policy recommendations challenge the school system to take accountability measures more seriously, especially with regard to charters.

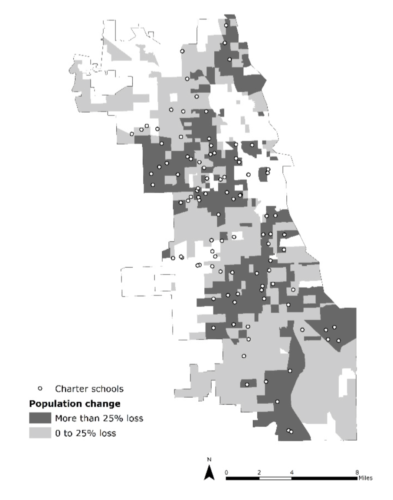

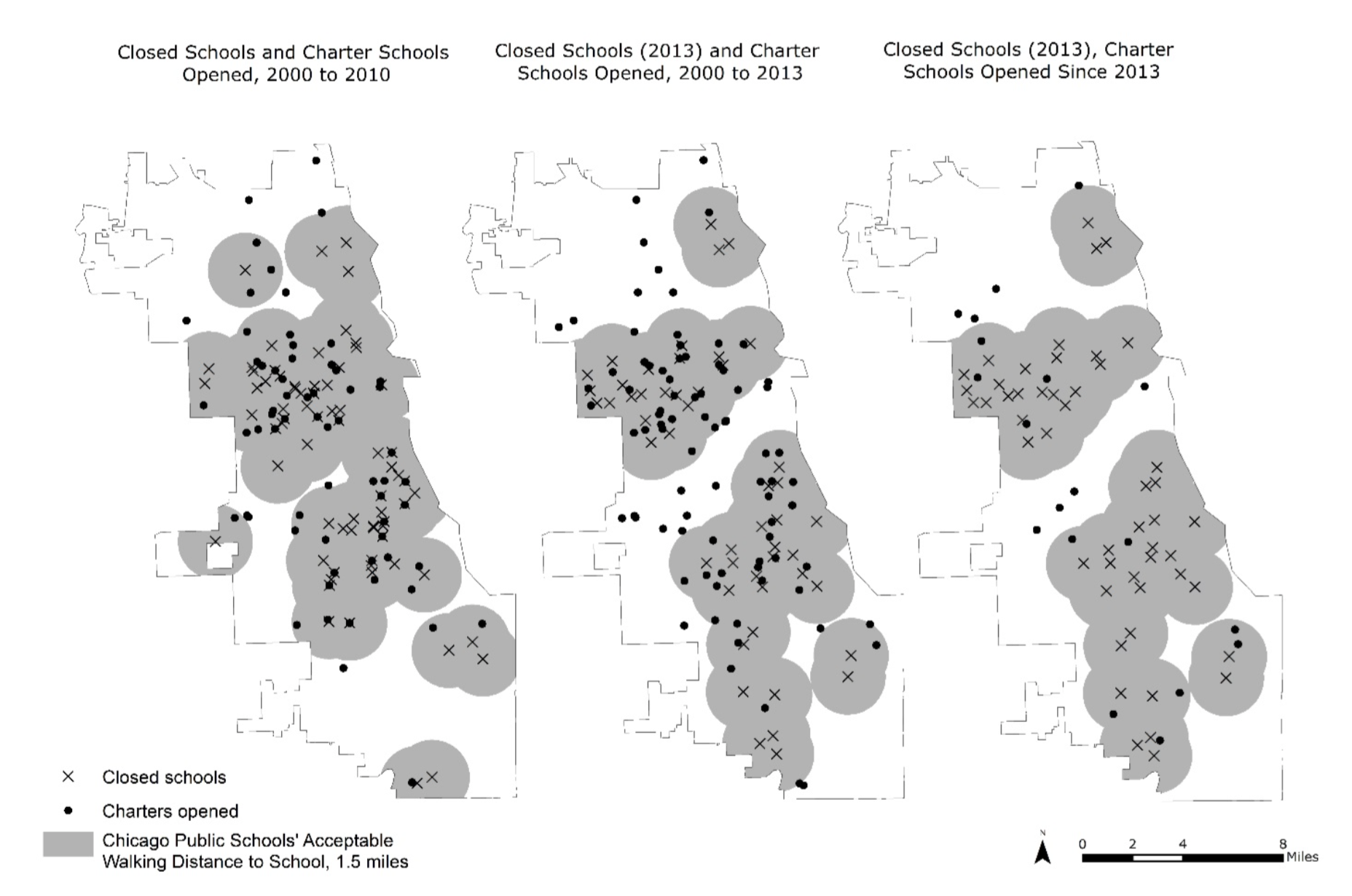

Using data from CPS, the Illinois State Board of Education, and the U.S. Census, analyzed with ArcGIS mapping software, Farmer’s team documented and compared changes in school-aged population, the locations of closed schools, the locations of new charters, and whether neighborhood public schools were deemed underutilized, overcrowded, or efficient. Analysis of these data points lead the researchers to three major conclusions: that the magnitude of CPS’s debt is mostly hidden, that the nature of charter expansion and placement has been all but unplanned, and that charters have diverted a significant amount of money from neighborhood public schools.

Farmer began compiling data for this study three years ago, when she began studying school closures following the 2013 shutdown of forty-nine CPS schools. Her experience in school finance research, however, reaches back to 2000 when she studied the relationship between schools and tax increment financing (TIF) districts. In a phone conversation with the Weekly, Farmer cited the tendency for new charters to be opened in neighborhoods with declining school-age population as the most surprising finding in this new study.

“This indicated to me that [CPS wasn’t] planning this process,” Farmer said. “It was just haphazard, ‘Let’s open a charter school’ without necessarily connecting it to the need across the school system.”

According to the study, eighty-five percent of the 108 charter schools opened between 2000 and 2015 were located in areas with a decreasing school-age population. Sixty-two percent were opened in areas with “high” school-age population loss, defined as a decrease of twenty-five percent or higher.

Between 2004 and 2015, CPS employed two policies when targeting schools for closure. The Renaissance 2010 (Ren10) initiative, announced by then-Mayor Richard M. Daley in 2004, sought to close sixty to seventy existing schools in exchange for one hundred new selective enrollment, contract, and charter schools. This initiative spoke to a new era of CPS governance that prioritized the “school choice movement,” now largely associated with conservatives such as Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos; rather than parents sending their children only and always to the local neighborhood public school, they would now have a range of choices for their child’s education without having to depend on private school options. The criteria for closure depended primarily on a new performance rating system tied to scores on the ITBS and ISAT tests for elementary schools and the PSAE for high schools. According to Farmer’s study, which defines the Ren10 period as 2001 through 2009, seventy-three schools were closed and replaced with eighty-seven new ones—sixty-eight of them charters, or seventy-eight percent of the total.

According to a 2009 study from the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research, CPS received complaints for its lack of transparency regarding its decisions to close schools for underperformance. Mounting pressure influenced CPS to adopt a “turnaround” policy, where low performing schools would undergo complete staff overhauls rather than close.

The election of Emanuel in 2011 brought a new system that relied on testing performance as well as enrollment to dictate school closures. In an attempt to “right-size” the district, the mayoral-controlled Chicago Board of Education determined that schools with a class size average of less than 24 were “underutilized” and those with an average over thirty-six were overcrowded. Previously, schools with utilization percentages—the percentage of average students per classroom with respect to the Board of Education’s “ideal utilization” of thirty students per classroom—below sixty-five were also considered underutilized.

A 2013 study by public school parent activist coalition Raise Your Hand for Illinois Public Education and CPS data research project Apples to Apples found, however, that during the 2012-13 school year, forty-seven percent of charter schools fell into the “underutilized” category. Farmer points to this discrepancy as evidence for CPS’s carelessness with regard to building unnecessary charter schools while simultaneously closing neighborhood ones.

“The opening of these [charter] schools is not in relation to where the actual need is,” Farmer said. “And so this is problematic when we’re in such scarcity—financial scarcity that is—that we can’t do this in a haphazard way.”

The CPS policy towards charter proliferation has changed in recent years, albeit only slightly. In 2015, Claypool announced a new warning policy meant to target underperforming charter schools for closure. Four schools, including two single-site charter schools, received closure recommendations in November 2015. In a CPS press release, Claypool said that the closures “were made to ensure better outcomes for students, and signal to charters not performing well, that they need to either improve or pack their bags.” Three of those schools, including Amandla Charter School, which the Weekly reported on in February 2016, remained open after appealing to the Illinois State Charter School Commission (SCSC), which is controlled by appointees of Governor Rauner .

Despite this show of toughness against underperforming charter schools, the results of Claypool’s policy demonstrate an important distinction between single-site schools like Amandla and powerful networks of charters like Noble, which has eighteen separate schools. Two of the four schools targeted for closure in September 2015 were single-site schools, even though they make up only about twenty percent of the 135 charters currently operating in CPS. Single-site charters also tend to be the brainchildren of teachers and social justice advocates, whereas networks are oftentimes not. Farmer notes that Claypool’s policy works to “eliminate [the] competition from the bigger chains.”

Farmer also noted that these two styles of charters differ in their financial interests, where networks tend to garner more support from “venture philanthropists” with deep pockets.

“That’s an interesting dynamic, especially when you’re talking about how, at this same time, the financial sector is seeking to erect a charter bond market,” Farmer said. “And of course, these charter bonds would be paid back with public revenues.”

Obtaining financial data about the city’s charters can prove challenging; just twenty-seven percent of them filed mandatory audits with the Illinois State Board of Education in 2015, reporting a combined debt of $277 million. Based on that number, Farmer speculated that the total debt of charter schools runs around $1 billion.

This debt, according to the study, is also wrapped up in the siphoning of resources from neighborhood schools to charter schools. The CPS adoption of Student Based Budgeting (SBB), a system in which schools are funded per student rather than per teacher, contributes to a “recursive cycle of student enrollment decline and budget cuts.” When a student moves from a neighborhood public school to a charter school, those tax dollars move with them. Neighborhood public schools feel the brunt of this loss, as overhead costs do not decrease with fewer students. Schools are then left with the choice to keep the school librarian or pay the electricity bill, while charters receive more money with every new student.

Farmer describes charter debt as “off-the-books,” in part because of lack of transparency. According to the state law governing charters, all charter schools are required to submit independent audits annually to “its authorizer and the State Board.” This doesn’t appear to be common practice, however.

Charter schools can also receive grants and private funding, but neither this information, nor the total share of charter debt, is included in the CPS Comprehensive Annual Financial Report.

“That kind of lack of accountability and transparency is very problematic because then the public doesn’t understand…the sheer magnitude of debt,” Farmer said. “Especially in light of how the debt itself has been used to justify school closures. Or, how the debt itself is being used to justify these cuts to education.”

Farmer’s report concludes with three policy recommendations: an immediate moratorium on charter school expansion, the creation of more accountability measures for charter schools, including a “school facility planning process,” and abolishing the SCSC.

The final measure addresses a charter school closure loophole of sorts, in which schools recommended for closure by the Chicago Board of Education can appeal to the SCSC to remain open. Three of the four charter schools threatened with closure in 2015 found success with this channel. Farmer says this method enables the SCSC to “bypass local control.” She also contends that this was always the primary aim of the SCSC, as it was based on legislation from the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, an organization known for authoring legislation establishing or expanding conservative ideals and spheres of influence in city halls and statehouses throughout the country.

“[The SCSC] was established not to have this kind of neutral regulatory body, it was established as a political body in its conception,” Farmer said.

In addition to highlighting the accountability and transparency problems for which CPS has been criticized previously, this study provides tangible data for the relationship between charter schools and school closures. A member of Chicagoland Researchers and Advocates for Transformative Education, an education research organization, Farmer expects her work to serve as a foundation for new research efforts focused on the free market school choice aspirations of DeVos and the Trump administration, exemplified by its support of vouchers that would allow public school students to attend private or religious schools with taxpayer money.

“In the study, I talk about how student based budgeting allows for the per-student allocation to travel with the student from a neighborhood school to a charter school,” Farmer said. “That’s precisely a voucher-like model. So [with] the lessons that we learn from this study…we can perhaps anticipate what would happen if we moved to a voucher-like system. So that’s where the next, I think, movement is going to take shape.”

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

great, great piece

This is incredibly rigorous journalism, I love all of the actual parents, students, alumni, teachers or staff from charter schools you spoke with and quoted in the article.

Also impressive that the author was able to make statements like, “single site charters tend to be the brain child of educators whereas networks are not” without any evidence whatsoever. Never mind that Noble (referenced in the prior sentence) was started by two CTU teachers.

The editors of the south side weekly must be proud of this level or rigor in reporting, basically a single source, Farmer, subsisdized by the CTU able to regurgitate “research” that has not been peer reviewed, nor published by an academic journal.

Hello:

I enjoyed the article, but I am just not seeing connection between charter schools and current CPS budget problems.

Overall message here is charter schools targeted ares with struggling schools, and after charter came in, the struggling schools lost even more students, forced to close. CPS spent less and less money on those schools, and now spend zero on those non existent schools. When you bring up SBB, does that mean CPS gives money per student or CPS gets money per student? If they get money per student, is that coming from state? City? I guess if CPS was getting money per student, then I can see the connection but if that is money per student that CPS gives to a school, then I am missing the connection, I would love to be enlightened here as I am trying to learn more about education and funding.

Thank you

Anon, if I may call you that. The subject of the article was a study published by Roosevelt University and authored by Prof. Farmer. It was not single sourced but rather several studies conducted by other entities were referenced for context and to underscore findings in the Roosevelt University. I get that you seem to think that it is a hit piece. However, can you cite some source to support that Prof. Farmer is not doing independent inquiry but rather is subsidized by the CTU?

Are you sure that two scrappy teachers with a vision and a plan started the Nobel network? Did they do a GoFundMe? Did they do car washes on weekends until they finally had enough money to start a scrappy little school that shared their scrappy vision. Was the plan just crazy enough to succeed. Or does the Nobel network largely exist due to the injection of capital from Ken Griffin, someone who is certainly no stranger than politics. You are no stranger to politics either are you, anon?

Why are schools being purposed for where enrollment is more likely to decline where other schools are closed where there is plenty enrollment. Why did Trumbull close? At the time it had close to 200 special needs students who were OMITTED from the utilization study making it seem as if the school was significantly emptier than it was each day. The study failed to count them although if you stood in the hallway you could count them everywhere you looked. We only see what our ideology allows us to see, don’t we, anon?

As someone who has been following this story for awhile, I can tell you that the story (and more importantly this study) adds to what is known. Your snark and cynicism add nothing to the debate on how elastic our brick and mortar schools should be.