Carl Sandburg’s poem, “Chicago,” introduces the City of the Big Shoulders while subverting the growing industrial powerhouse’s uglier sides by highlighting the city’s boldness, cunning, and ferocity. Sandburg published the poem in 1914, when literature was a titan of media. Art and entertainment have long competed with the news media in characterizing Chicago, and that has been the case in radio, television, the silver screen, and the internet.

To get a sense of South Siders’ thoughts about how the media has portrayed Chicago, I spoke with three other millennials from the South Side. We discussed growing up in the ‘90s, later dealing with the Chiraqification of the South Side and overall media representation of life in Chicago. Our conversations ranged from news and music to dealing with the city’s reality and perception of violence. These interviews were conducted in 2023, which saw the cancellation of the streaming series, South Side, and the rise of the critically acclaimed show, The Bear.

Though I grew up in poverty in Englewood, surrounded by gangs, my interviewees had Black middle-class upbringings on the South Side. Jeremy Jones is a DJ, producer, and eclectic creative from Englewood who only briefly lived outside of Chicago in the early 2010s. Brittany Norment is a social media marketing and communications consultant from Englewood; she grew up in England and lived outside the City as a military brat for ten years. Melanie Shaw is a professional cosmetologist and makeup artist who has worked on the sets of One Chicago Franchise, South Side, and The Bear, and has lived in Chicago her whole life.

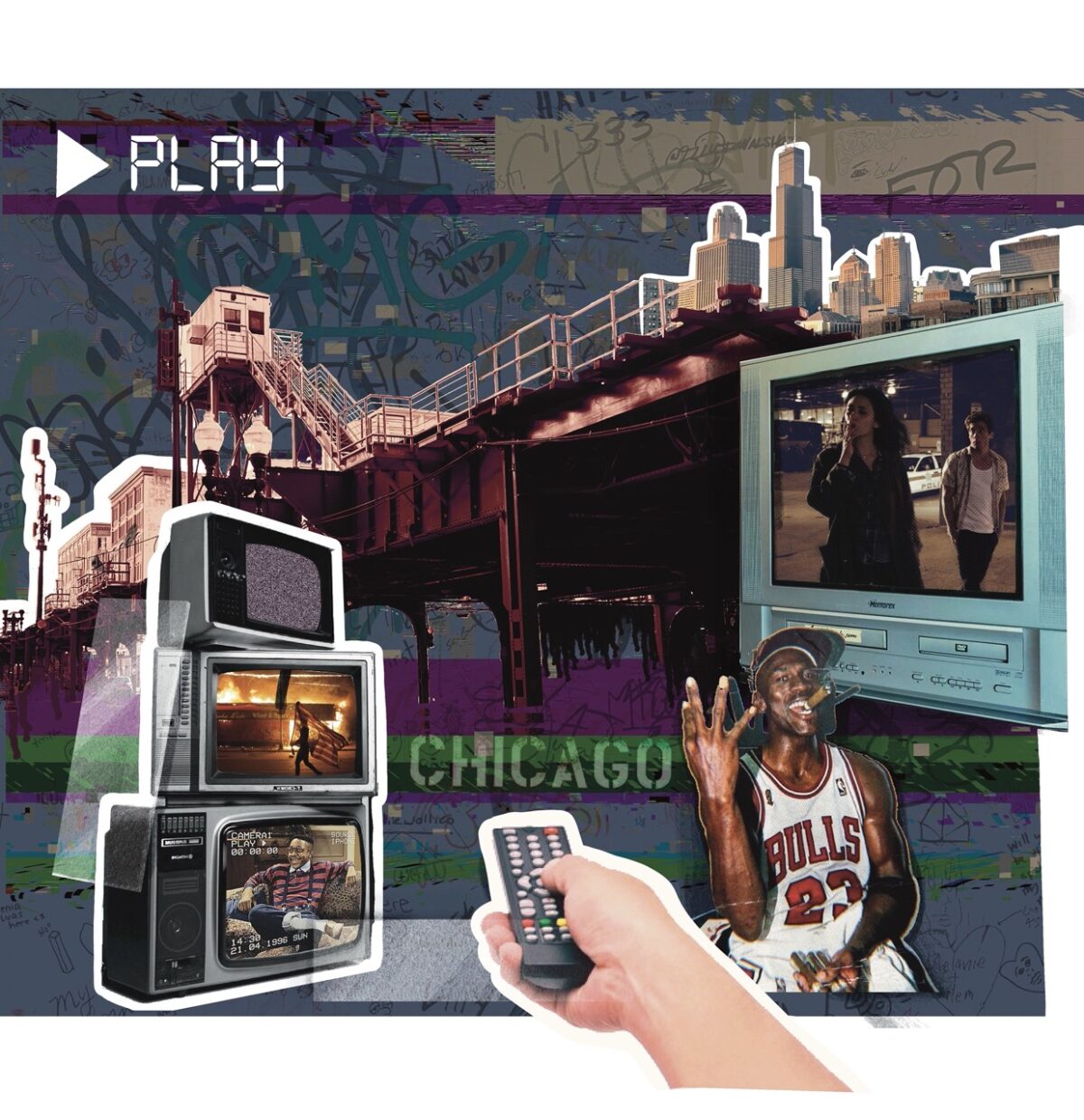

“You had a guy who was known as the GOAT of basketball history, so why would they want to portray [Chicago] as a bad city?” Jeremy asked. In the ’90s, the Bulls had a legendary run under the leadership of Micheal Jordan and Phil Jackson. Remembering the days when people celebrated championships for nearly a decade, Melanie talked about how people would drive by honking their horns and setting off fireworks. “Some people would let off gunshots,” she admitted, “but yeah, those years had such a static in the air.”

While the media was covering the Bulls’ legendary run, it was also busy portraying Chicago as a city of violence. The news media focused on the street celebrations after the Bulls victories and compared them to rioting, setting the tone on how, even in the jubilee, Chicago had a reputation to live up to. In ’91, ’92, and ’93, there was a focus on the spillover of the celebrations that was politicized by out-of-town reporters.

Social demographer Michael Rosenfield conducted a study about this media coverage and its focus on select neighborhoods, analyzing the concentrated poverty, political grievances, and the national versus local narrative. One major point of the study was that a supermajority of “rioters” were Black, and the way the police handled the South and West Sides was much different than how they handled the unrest downtown and on the North Side.

The term superpredators was introduced in 1995 by political scientist John DiIulio Jr., who used it in conservative political magazine The Weekly Standard to describe the rise in violence for those who were coming of age in the ’90s. Both political parties used this term, and the catalyst event was the killing of Robert Sandifer, an eleven-year-old from Roseland who was allegedly part of the Black Disciples gang. The national media focused on violence in cities like Chicago, and continued to paint the “inner city” as a war zone. This dehumanization and sensationalism continued the trend of painting predominantly Black communities as primarily dangerous.

When Brittany’s family lived on 65th and Green, she said, “My block was a very hot block, like, we had drive-bys constantly,” which is why many parents taught their kids to avoid certain areas. This block-centric perspective for surviving the violence is how many parents coped with the reality of the era, which was constantly echoed in the evening news. Even South Siders who weren’t directly impacted by the violence existed in a world where hypervigilance was reinforced on multiple fronts.

Reminiscing over Chicago history reminded us of classic shows set in the Windy City. Melanie brought up Good Times, which was set in the infamous Cabrini Green projects, to challenge the depiction of lower-class trappings and presumptions about Black fatherhood. “I watched a lot of Good Times because my mom and brothers watched the show all the time,” she said Good Times depicted a resilient family that sought to overcome their plight in America—that is, before the show became too invested in the comedic tropes of Jimmie Walker.

With so many shows depicting South Side life, Family Matters and The Steve Harvey Show were the centerpiece sitcoms of our millennial lives. Jeremy felt this was proven in Family Matters, saying Steve Urkel “was kind of a quirky hipster who will probably invent some type of technology.”

We all brought up Family Matters, a show that aired on ABC and CBS from 1989 to ’98 about a middle class family in Chicago, where Steve Urkel famously graced the screen with his whimsical antics and mad-scientist-level genius. “I enjoyed that they showed a Black family that wasn’t just the Cosby Show, in a light where they were middle class, they lived in a beautiful house, they had a nice family, and it was funny,” Melanie said.

“I grew up with Family Matters where you go to watch Urkel grow up as a young man in Chicago, but Carl Winslow is a cop,” Jeremy said. “Urkel’s not into basketball, he’s not into sports, that’s kind of more Eddie Winslow’s thing.”

Millennials came of age in the 2000s, and two major events for Chicagoans were the election of President Barack Obama and the rise of drill music. Obama’s election put a national focus on Chicago, which Melanie described as creating “electricity” throughout the City. But drill music created a depiction of gang violence that reanimated the narrative of Chicago as a dangerous city.

The news media and entertainment media complemented each other in reinforcing the narrative of Chicago violence. Drill music is the evolution of gangsta rap pioneered by Bump J in the early 2000s and brought to the mainstream with the explosion of Chief Keef and the release of his debut album in 2012. It paired with Chicago’s reputation in the news media, which “gave Chicago a modern gangster persona, to everyone else, but we all knew what was happening,” Melanie said. “I don’t think that it’s for everybody, [given] all the violence, but some of those kids are just telling a story about their lives that they wouldn’t be able to tell in any other way.”

The fact that drill was instantly exported around the world showcased Chicago, no matter how you viewed its impact, and could connect with a wide range of people. Brittany confirmed this with an experience she had working at Lollapalooza in 2022. “They started to play Faneto by Chief Keef, and Lollapalooza is just a ton of white people and some people of color, but mostly young white kids from the suburbs and the North Side, and they went crazy,” she laughed, while adding “Faneto was their anthem and I thought that was our anthem.”

Jeremy, who had moved to Texas and California near the end of the 2010s, recalled often being asked, after telling people he was from Chicago, “‘Oh my god! Is that city as bad as I’ve heard?’ and I always had the follow-up questions of, ‘How bad did you hear? What do you think it is?’” He added, “they would always say ‘I heard it’s dangerous there, you could get killed just standing at the bus stop.’”

Though he wasn’t fully aware of who was creating this narrative, Jeremy said he often questioned these folks further with “‘What type of image are you hearing? Who told you that? Because that’s not what a person from Chicago would tell you.’”

As our conversations approached more modern media, certain shows had to be mentioned, specifically the One Chicago franchise shows about emergency responders that air on NBC. Melanie worked on Chicago PD for two years, as well as Chicago Fire, and said she felt that the One Chicago Franchise shows have become a staple in the city.

“I feel like those shows can be more of a soap opera and I do feel like some of those shows can also not necessarily be about the city, but those shows have provided a ton of jobs for people and all three of those shows film ten months out of the year,” she said.

In regards to whether The Chi, a Showtime drama that depicts life in a fictional neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, represents Chicago authentically or not, Brittany said, “I feel like it depicted Chicago well, then on top that the fact I knew so many people involved in it with guest spots and stuff, so it was Chicago because it was being filmed here… and the way it visually depicted stuff felt very Chicago.”

She had this to say about why she didn’t stick with the show. “Seeing familiar streets and whatnot is always cool, but the drama of it all, and the story they were telling, I am very much at a place in my life where I am very tired of watching Black trauma.”

Shameless, another Showtime adaptation of a British television series that depicted life on the South Side of Chicago, had a different take on the city. “Even though it was about a white family, it was still very relatable because they were a mess, as we are typically given a middle-class blue collar family,” Brittany said. “So to have this family that was lower class, or in poverty, that is an absolute mess, was really interesting to me because it felt more reflective of real life.”

Shameless, The One Chicago franchise, and The Chi present Chicago as a melodrama playing into the news media narrative of what life in Chicago is while having flaws that locals can’t ignore. Shameless is one of the most popular shows about Chicago and fostered empathy for its predominantly white cast, but it’s hard to accept that this family is actually living in a South Side neighborhood.

One Chicago’s shows are an engine for those working in the entertainment industry, but do little to counter the narrative due to their framework being an institutional point of view of the city that reinforces the idea that, outside of the professional environment, there is not much more than death and violence waiting.

The Chi, actually created by a Chicago native, started off weaving plots that sensationalize the violence of living in the Black community, yet its dependence on melodrama kept the story lines in the same vein as soap operas that need the city to be a dangerous place.

In 2023, South Side, a sitcom that premiered on Comedy Central before moving to HBO Max, was canceled after three seasons. All the interviewees praised the show, pointing to the authenticity of its Englewood and South Side Chicago representation, the fun and zaniness of its sketch comedy influence, and the relatable characters. The show demonstrated how South Siders hustle, how archetypes are given lines that not only humanize their positions in life but subvert expectation, and that it used comedy to showcase what is a favorite depiction of the community where I was born.

“What South Side shows are two brothers from the South Side of Chicago trying to make it,” said Jeremy. “And it’s not shy about it, which I find different from shows like Steve Harvey and Good Times.”

Jeremy then talked about the sketch comedy history of Chicago and how even Kel Mitchell’s character from Good Burger could fit in the show’s environment, pointing to “the fact that they bring that same Key and Peele comedy style back” as a quality of the show to be admired.

Brittany talked about the subversion of character archetypes and the fact that something positive was found in every character. Officer Turner, a character on the show, “was so great to me because I love that she was a cop and she was also just a regular Black woman that you would probably meet somewhere,” Brittany said. “And the fact they kept giving her different wigs on the regular warmed my heart with joy,” and made her seem more real.

“She was a reflection of so many different types of women from Chicago, but her attitude was quintessential South Side; she went to Morgan Park, you know she grew up in the hood somewhere, probably on 79th street, and she probably became a cop because she was in the program as a teenager and stuck with it because she makes good money and uses it to go to a Beyonce concert.”

For Melanie, South Side was unique because it was a union job and her first time getting mentioned in the credits. She talked about how grueling it was working fourteen-hour days, especially on the first season when the budget was smaller, but this allowed her to get to know and appreciate the cast of actors and writers.

This closeness of the team was also seen on the writing side, as she talked about how it was around thirteen writers who just happened to also be mostly on the screen and were adept at making the ridiculous scenes.

“Chicago is a city of improv and comedy,” Melanie said. “So many people from SNL, especially from the ’80s and ’90s, came from here [and] went to Second City… the people from Chicago are funny as hell and I think South Side did a good job showing that.”

Cordell Longstreath is a veteran, writer, community advocate and activist, and teacher. He last contributed to the Weekly’s Englewood section of Best of the South Side 2022.

This article really makes one think. I’ve never thought about how Chicago is presented to outsiders. But, the issues mentioned here are true. I’ve lived in Chicago for over 20 years; and relatives and friends, who live in other states, see Chicago as just a dangerous place. They are constantly telling me to “stay safe”. I love Chicago. Yes, there is crime and violence, but that exists everywhere. Lack of equal opportunity causes most crime (other than the crimes committed by the upper/privileged sector — those who are not held accountable, who are above the law). That’s a proven fact. Thank you for this article because it has opened my eyes in so many ways.