On Wednesday, July 12, 1995, Chicago sweltered. A heat wave rolled in and clung to the city for five days. Roads cracked open and bridges were hosed down to prevent them from locking in place under the sun. And even though infrastructure faltered, the city waited four days to declare a heat emergency, delaying the mobilization of additional workers in the fire and police departments to check on elderly citizens and get more ambulances on the roads. Mayor Richard M. Daley, staying as cool as possible and alluding to the city’s ability to manage hazardous weather events, said during a news briefing: “It’s hot. It’s very hot…. We go to extremes in Chicago. And that’s why people like Chicago. We go to extremes.” The decision to not treat this natural disaster seriously would cost the lives of hundreds of Chicagoans.

Now, twenty-five years later, Chicago faces another extreme public health crisis: the COVID-19 pandemic. And like the heat wave of 1995, COVID-19 disproportionately impacts older Black and brown Chicagoans, leaving residents and officials questioning the policies that have divided the city and weakened communities of color, all the while wondering what can be done to repair the decades-long inequity in Chicago’s public health infrastructure.

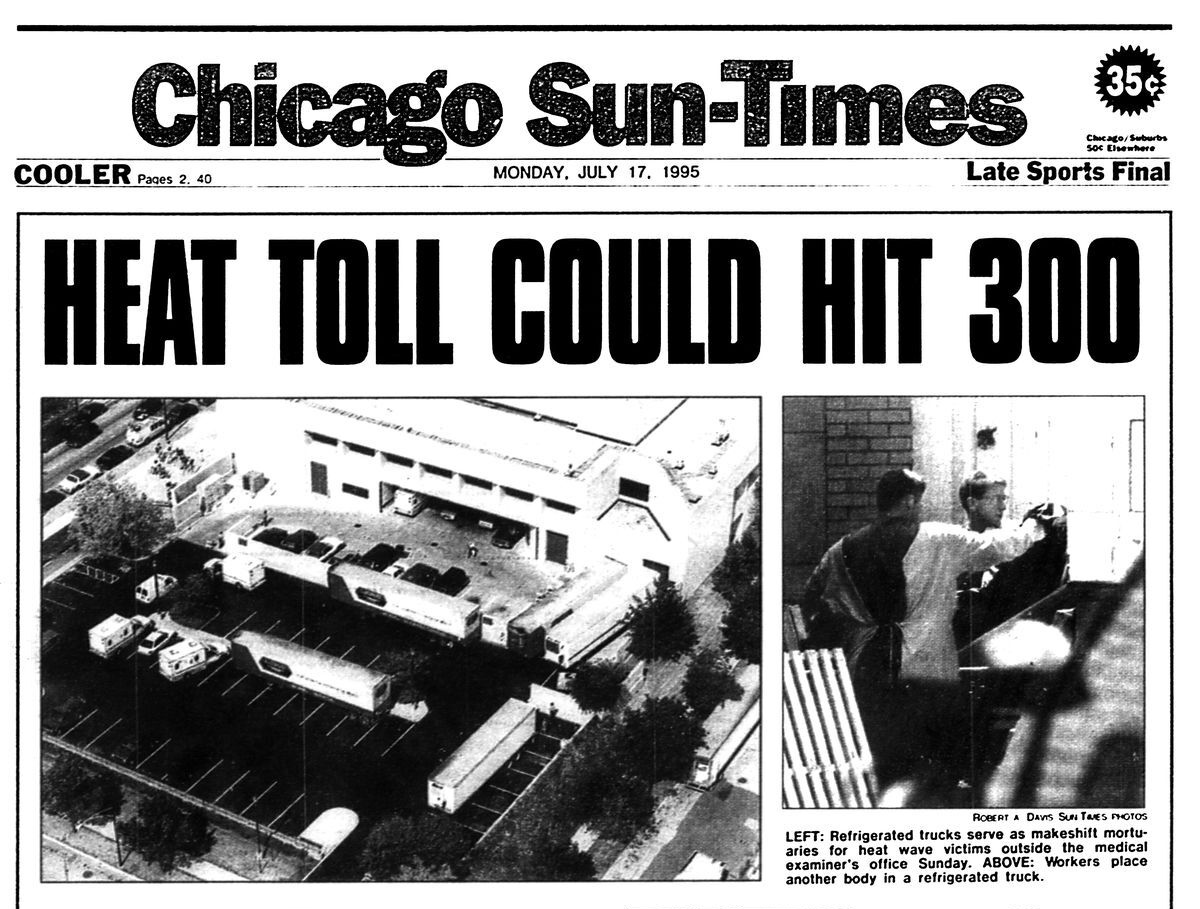

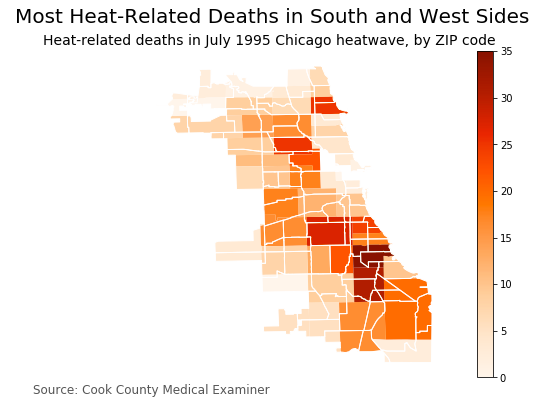

Back in 1995, 105 degree Fahrenheit days seemed like business as usual in a city known for its hot summers. But the city’s citizens began to suffer in the second week of July as the heat index reached 125 degrees F, coupled with high humidity. Thousands of fire hydrants were opened up across town as people tried to cool off, and the demand for air conditioning overloaded a strained electricity grid, hurling tens of thousands of residences into blackouts. Calls to 911 for medical assistance skyrocketed above daily norms, and emergency departments became so overwhelmed that at one point, twenty-three different hospitals, mostly on the South and Southwest Sides, stopped taking new patients from ambulances. By that weekend, the city had hired refrigerated trucks to sit outside the chief medical examiner’s office to hold the additional bodies that could not fit in the city morgue, which only had room for 200 occupants. Bridget Vaughn, a lifelong South Sider who was in her thirties during the heat wave, recounts: “The scary part of the heat wave was to every day listen to all the numbers of people dying. It was like the city really didn’t have a plan.” (Vaughn has been a South Side Weekly contributor over the years.) The final toll was 739 lives lost, dead from heat exhaustion and complications resulting from the heat wave. Those who died were mostly older and poorer Chicagoans, and Black Chicagoans were disproportionately affected.

The Mayor’s Commission, tasked with determining what had led to so many deaths, declared the event “a unique meteorological event.” But some people disagree with this assessment. Eric Klinenberg, a social scientist born and raised in Chicago but currently at New York University, wrote in his 2002 book Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago: “Hundreds of Chicago residents died alone, behind locked doors and sealed windows, out of contact with friends, family, and neighbors, unassisted by public agencies or community groups. There’s nothing natural about that.”

In the aftermath of the heat wave, Chicago invested in policies, community education, and cooling centers designed to limit future heat-related deaths—but did nothing to change what had caused some neighborhoods to be overwhelmed by the emergency, such as weakened transportation systems, rising utility costs, shuttered hospitals, and failing commercial districts. When another heat wave hit the city in 1999, only 103 people died and it was celebrated as a victory of Chicago’s “Extreme Weather Operations Plan.” But the same demographic was hit: older Black Chicagoans living alone in apartments. Many who died were living in apartments with air conditioning units that had gone unrepaired or were no longer functioning because of power outages.

In 1999, Klinenberg published an academic paper on the heat wave, in which he wrote that “Chicago has at least learned how to handle the heat during isolated emergencies, and it is unlikely that another heat wave will prove so disastrous for the city again. Will something else?”

The COVID-19 pandemic is that something else, once again bringing to light the devastation that can occur at the intersection of public health emergencies and structural racism.

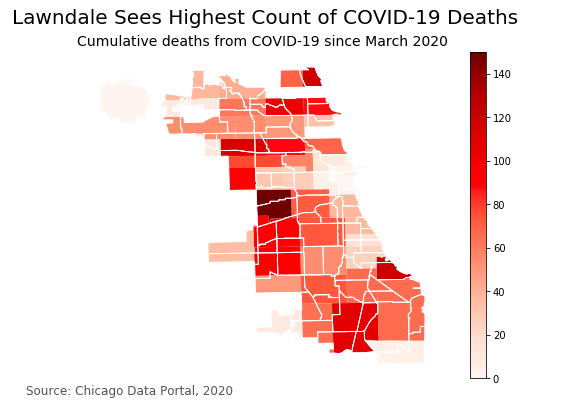

As of July 10, the total number of COVID deaths in Chicago has surpassed 2,600, with eighty-one percent of these deaths occurring among people of color. On April 20, 2020, the Mayor’s office deployed the “Racial Equity Rapid Response Team” to attempt to lessen the burden of COVID-19 in three communities of color on the South and West Sides where cases were concentrated. At that time, there had been 683 COVID-related deaths in Chicago, eighty-four percent of whom were people of color.

In 1995, not all South Side neighborhoods were affected equally by the heat. In fact, some majority Black neighborhoods on the South Side—Washington Heights, Morgan Park—suffered few casualties during the heat wave. Similar patterns have played out during COVID, which suggests that it isn’t just poverty or race which makes people vulnerable. Klinenberg points to city abandonment as the larger issue that explains why some die and some survive. Areas that suffered from the heat wave most had been abandoned—by city resources, private industries, and residents. Abandonment and decay made social support systems difficult to maintain. These causes for increased death during heat waves were not addressed as part of Chicago’s Extreme Weather Operations Plan. This process of addressing an issue but not its underlying causes has perpetuated health inequity in the city of Chicago and leaves the city’s populace vulnerable.

Even though COVID-19 and heat waves are more dangerous for older adults, the people who die from heat waves are not necessarily the same people who die from COVID-19. Heat waves impact older people who live alone and in buildings with non-functioning air conditioning units. COVID-19 is less likely to infect you if you’re living alone, and it doesn’t care about your thermostat. Additionally, if you experience heat stroke, getting to an emergency room where you can get intravenous fluids might be enough to prevent you from dying. If you contract COVID-19 and require hospitalization, there’s a thirty percent chance you will require some time in an actual ICU bed for additional oxygen therapy.

And yet, despite these health conditions being so different, in Chicago they have affected the same people. Even the Chicago measles outbreak of 1989, a disease of infants and young children that claimed the lives of eight, was disproportionately represented in Black and Latinx patients.

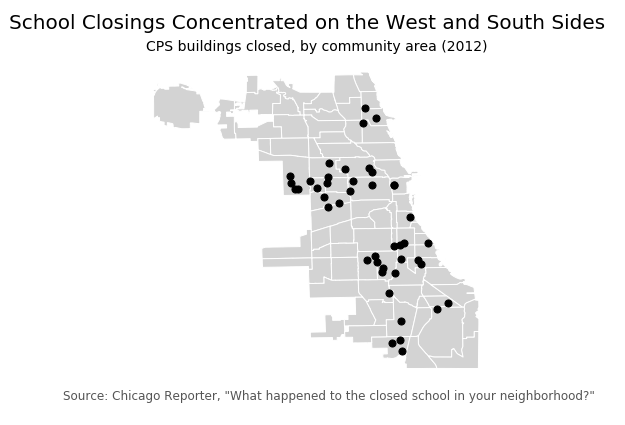

That COVID-19 is affecting the same communities that have seen a disproportionate amount of school and hospital closures, as well as economic disinvestment, is hardly surprising, because ultimately it is not about the emergency. A disinvested community will have less resources and less resilience in the face of any emergency that comes to threaten it.

During the two-and-a-half decades between the 1995 heat wave and the COVID-19 pandemic, the standard of living for many Chicagoans worsened. Healthcare, education, grocery stores, and well-paying jobs were continually driven from the South Side of Chicago. This not only affected residents’ lives, but accelerated Black flight from these communities, further depleting neighborhoods of tax revenue and community support. Between 2000 and 2014, three South Side hospitals were shut down, representing a loss of 660 inpatient beds and over 2,000 full time jobs in those areas. Even now, amidst the COVID crisis, four safety-net hospitals on Chicago’s South and West Sides—Advocate Trinity, South Shore, St. Bernard, and Mercy Hospitals—that have been annually underpaid through state Medicaid reimbursements and have a combined yearly deficit of around $76 million, are struggling to stay afloat. Their plan to recoup a billion dollars in funding and merge into a larger healthcare network was denied by the state in May 2020, in the midst of a pandemic which requires hospitals to be functioning at peak efficiency. Now their futures—and the futures of Chicagoans who depend on them for healthcare—remain uncertain.

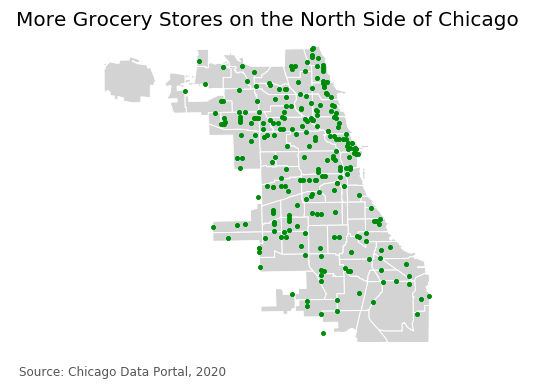

But it’s not just hospitals that have been hurt by disinvestment. Homes on the South Side have been torn down and not built back up, and public transportation options have long been inadequate. These issues lead to communities being “less livable” and less commercially viable. It’s a slow-burning disaster that, over time, has perpetuated the city’s life expectancy gap. Research has shown that Chicago has the largest life expectancy gap between zip codes of any large city in America; people who live in 60611 (Streeterville) live on average thirty years longer than people living in 60621 (Englewood).

Chicago physician and epidemiologist Dr. David Ansell investigates this problem in his book The Death Gap. According to Ansell, people make assumptions about why the gap is so large, blaming gun violence as the driver for the life expectancy difference, when the real causes of early death in poor neighborhoods are heart disease, exacerbated by poverty, stress from poor housing standards, unfair policing, low wage jobs, lack of access to healthy food, and inaccessible healthcare due to the large numbers of uninsured and underinsured Chicagoans living on the South Side. Addressing just one of these issues is not enough to make a meaningful impact. All of these inequities—known together as “structural violence”—must be addressed and challenged to ensure that people are no longer caught up in the laws, policies, procedures, and norms that make them easy targets for the next crisis.

Health inequities—the preventable disparities in health outcomes between different groups of people—touch every sphere of life, and are consequently impossible to address through a single policy channel. Health inequity has always been a pressing issue in Chicago, but there are multiple community organizations—and even groups within city government—dedicating themselves to equalizing the huge health gaps that are affecting citizens. In November 2018, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle revealed a five-year road map for Cook County that was built on pillars of equity, naming the government’s historical role in creating and maintaining racial inequities. And during the inaugural Racial Equity Week in September 2019, Preckwinkle opened with a speech calling for specific initiatives around equity in transportation, healthcare access, and broadband internet access.

Dennis Deer, a Cook County Commissioner and clinical psychologist, introduced a unanimously passed ordinance one year ago, in July 2019, titled “Declaring Racism and Racial Inequality a Public Health Crisis in Cook County.” At a recent online convening discussing the heat wave and COVID-19, he said he wanted to make sure that racial justice isn’t just talked about and then forgotten, and that Cook County commits to considering legislative outcomes with a racial equity lens moving forward. The ordinance calls for increased diversity in the office under the Board President, educational training for staff about how racism affects individuals, and advocates for relevant policies that improve health in communities of color and initiatives that advance social justice. Commissioner Deer wanted to make sure that the city does more than just “talking the talk.” But only time will tell what the current government will accomplish.

As part of the report from her transition team, Mayor Lightfoot received recommendations on how to address racial equity in her first 100 days in office, like publicly setting benchmarks that need to be met to demonstrate measurable improvement. A year later, she has managed to accomplish only a few of those goals, such as creating the Office of Equity and Racial Justice and hiring Candace Moore as the Chief Equity Officer.

However, a number of community organizations have taken it upon themselves to minimize the life expectancy gap. Founded in 2013, by Robbin Carroll, I Grow Chicago was started to address the negative impacts of violence and trauma in the community of Greater Englewood. Over time, their goals have become more holistic, realizing that to make change you have to look at the entire picture. They now address social determinants of health to improve the lives of their community. During COVID, they have been bringing groceries and supplies to neighbors, running tutoring classes for kids stuck at home, donating laptops to children who need to complete remote classes, and hosting free COVID testing. So far, they have donated thousands of masks, gloves, and thermometers. Zelda Mayer, I Grow Chicago’s director of development, said that she hopes that one day their services will not be required, a day when “residents of Chicago no longer need deliveries of clean drinking water or food, a world where all our neighbors have safe housing, good schools, fulfilling work, and loving communities.” In order to move to that future, Mayer said structural racism needs to be addressed by the city.

“We must all acknowledge, confront, and dismantle racism in all areas of life,” she said. “As part of this work, our city agencies must look at our resource structures and how accessible they are. I Grow Chicago, and other small nonprofits, [are] not the end-all be-all solution. We are working towards a world beyond nonprofits filling in the gap created by unjust distribution of resources in our government.”

The push to provide basic goods and services to individuals within the city has extended beyond traditional nonprofits into mutual aid groups supporting communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and, more recently, in reaction to the uprisings over the murder of George Floyd and police brutality. The compounding of issues has left everyday Chicagoans helping each other, filling the gaps left by inequities never meaningfully addressed by the city.

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

Bridget Vaughn remembers watching television during the 1995 heat wave: “It was disproportionately African American people that we saw dying, and that always makes me angry, that we are always the ones who are affected. That has always been frustrating to me.” At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Vaughn was impressed by the way the city moved quickly to turn McCormick Place and the United Center into emergency field hospitals. But quick, emergency responses do nothing to address chronic crises like food deserts and inaccessible healthcare. “The systemic racism in Chicago has been there since its founding,” she said. “And it’s rearing its ugly head the older and older and older it gets. And it pisses me off.”

The city has shown that it can improve the way it responds to extreme crises. With the spotlight on racial equity around the country and leaders of its government calling for equity driven approaches, maybe during future crises, deaths in Chicago will not fall so predictably along the lines of race.

Elora Apantaku is a medical doctor and writer. This is her first piece for the Weekly.

Charmaine Runes is a fact-checker for the Weekly and a graduate student at the University of Chicago’s Computational Analysis and Public Policy program. She codes for the people.