Over the last two weekends of July, the City held three public engagement forums for the 2023 budget. The forums were meant to give participants an opportunity to help inform the City’s budget planning through small roundtable conversations with leaders in local government. Yet numerous problems, from low turnout to a protest that halted the third forum, raise questions about how meaningful public feedback on the budget can be.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s administration has sought public engagement on the budget each year since she was elected. In the first two years, the City held a series of in-person and virtual town halls. Participation soared. Attendees had the opportunity to provide public comment and submit questions for City personnel to answer.

Last year, the administration shifted its strategy and partnered with the University of Illinois Chicago’s Great Cities Institute to further hone budget engagement. There were three forums open to all members of the public, plus three more for invited community leaders. Though the public forums featured more intimate discussions with officials than in the past, participation plummeted.

Each of the forums this year began with an introduction to the budget, including a video about past initiatives and current priorities. The video explained that the 2022 budget is approximately $16.7 billion and funds the City’s thirty-five departments.

“These are more than just numbers,” Budget Director Susie Park said at the first forum, which took place on July 21 at Kennedy-King College in Englewood. “They represent real lifelines, programming resources and money that will reach our residents.”

Participants had an hour to speak with high-ranking City personnel, including commissioners and deputy commissioners. The hour was split into segments to cover four topics: Community safety, affordable housing, public health, and community developments. The City personnel rotated to different participants’ tables for each segment.

3rd Ward Alderperson Pat Dowell, chairperson of the City Council’s budget committee, encouraged all members of the public to speak their minds. “No idea is wacky,” she said.

In addition to the roundtable discussions, participants were asked to complete a survey on the four topics. That survey was available online in English and Spanish through August 7 for residents who were not able to attend a forum.

According to Jacob Nudelman, a Deputy Director of the Office of Budget and Management (OBM), the forums are a two-way street. He said he hopes the forums help participants learn about City programs and services. But he emphasized the importance of resident input. Information from the forums and the survey will be incorporated into the City’s annual Budget Engagement Report, which he said is “extremely helpful” in creating the budget.

Nudelman pointed to an appropriation of $1.3 million in this year’s Fire Department budget for a mobile integrated healthcare program as an example of resident input having a direct impact on a line item in the city’s multibillion-dollar budget. That program provides healthcare services to underserved areas and helps direct people to the best places for further care.

More generally, though, the Office pointed to its 2022 Responsive Initiatives report as an overview of how residents’ broader priorities were integrated into the city budget.

It seems Lightfoot’s administration has used public input as a guide but not as a strict directive.

For example, the City received more than 38,000 responses to its budget survey in 2020, and seventy-seven percent suggested the City divert funds away from the police department to fill shortfalls in other areas. Those responses came amidst an outcry from advocates to defund the police in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

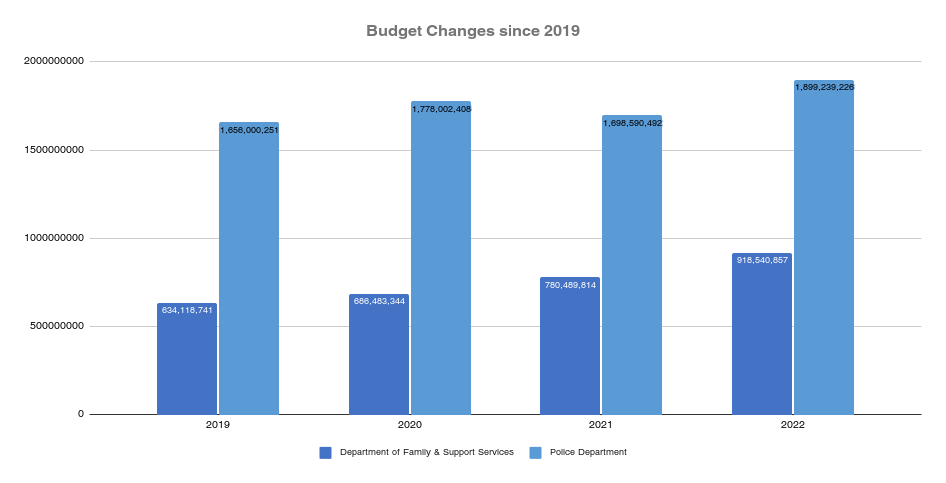

Lightfoot has not slashed the police budget—it has grown—but she has prioritized funding other areas of the budget at a higher rate. Since 2020, the City has increased the Department of Family and Support Services budget by thirty-four percent. The city has increased the Police Department budget by seven percent.

The City struggled with low turnout at this year’s forums, limiting the completeness and diversity of the public’s feedback. About 150 people attended the first forum, but most of them appeared to be City personnel. Of the approximately forty tables at the event, most were vacant.

At the second forum, which took place on July 23 at Malcolm X College on the Near West Side, participation was similarly low.

Martina Hone, the City’s chief engagement officer, acknowledged that she had been hoping for better turnout. She even asked participants to contact her office with feedback on how to improve engagement. “I would love help cracking this nut,” she said. “This was on Eventbrite. It was on all of our social media channels. We reached out to all of the aldermen. It was in our newsletter. But we don’t have a budget to buy TV ads like Pepsi does. We don’t use your tax dollars that way.”

In a later email to the Weekly, a spokesperson for the Office of Budget and Management reiterated that there was no budget for promoting the forums, but that the City did targeted outreach via digital billboards, radio and TV interviews in English and Spanish, and emails to all City employees and departments.

Some participants at the first forum were also unhappy with how the engagement process itself was designed.

Lakeview resident Anna Wertheim complained that long forums are a bad format for hearing from vulnerable people. She suggested that the City more proactively seek out residents to give feedback. “If you don’t have money, time and resources to be here,” Wertheim said, “then your voice is probably one that needs to be heard.”

Asha Ransby-Sporn, a Woodlawn resident and community organizer for the Treatment Not Trauma campaign, said the City’s survey was poorly designed for capturing thorough feedback. The survey asked participants to choose only one service in each topic area that was most important. Respondents could not rank services, and printed versions of the survey had limited space for elaboration.

She also said City leaders were “just bragging” or defending their work against criticism. At one moment she clashed with Tiffany Patton-Burnside, the Senior Director of Crisis Services at the Chicago Department of Public Health.

Ransby-Sporn questioned the City’s goal of funding more mental health crisis intervention training for police. She cited data from the City’s co-responder pilot program wherein the Fire Department, paramedics, and behavioral health workers respond to a portion of mental health-related 911 calls. Police also respond to some calls as part of the pilot, but program data from the past eleven months indicate that not a single call has required the use of force. For that reason, Ransby-Sporn questioned why the City would not instead invest in a different type of program that both expands the number of non-police first responders and reopens mental health clinics.

Patton-Burnside acknowledged the criticism but pushed back. She said police training is necessary to prepare for situations that could be too dangerous for community health workers. Polite but tense, the two argued over the likelihood of dangerous mental health events.

Budget engagement took a turn at the third forum, which was held on July 30 in Uptown at Harry S. Truman College. Advocates with the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, One Northside, and the Bring Chicago Home movement spearheaded a demonstration midway through.

Some seventy-five people stood up in unison. They chanted and demanded to meet with Lightfoot, who was attending the forum. Lightfoot did not address the protesters.

The demonstration was peaceful, and the protesters obliged when police ushered them out of the room after a half hour.

“58K need a place to stay” was the protestors’ most frequent chant, a reference to the Coalition’s estimate that 58,273 Chicagoans were experiencing homelessness as of 2019. The City’s estimate for that year was only 5,290.

Though the estimates are dramatically different, data from the Coalition and the City both show that homelessness in Chicago has declined by about thirty-three percent since 2015.

Still, the Coalition demanded more action from the city. Myron Byrd, a grassroots leader for the Coalition, refuted the City’s homelessness estimate and criticized Lightfoot. “She’s turned our back on us,” he told the crowd.

The Coalition has advocated for a tax increase on sales of properties exceeding $1 million in value to create a designated revenue stream for homelessness programs and services. The change would yield about $158 million in revenue per year, according to an analysis from Crain’s Chicago Business. Last month, seventeen alderpersons sponsored a resolution to create a public referendum on the tax increase.

Lightfoot has previously supported increasing the property tax to boost overall revenues, but she opposed using the change to create a dedicated funding source to combat homelessness, as reported by the Sun-Times.

Lightfoot waited until the demonstration dispersed to address the crowd. “Those people are entitled to exercise their first amendment rights,” she said of the protesters. “But we wanted to make sure that people had an opportunity to hear, to learn and to engage.”

There were approximately 225 people in attendance at the event’s start and perhaps half that number after the demonstration. Hone, the chief engagement officer, assured participants that their input would still be captured despite the disruption.

Participants at this forum seemed to have a more positive experience than residents at the first two forums, even with the interruption. Many felt heard.

Uptown residents Liz Soehngen and Laura Friedrick both said they appreciated having a chance to speak directly with City personnel. “They were really passionate about what they are doing,” Soehngen said. “They wanted to hear about problems, and they wanted to hear about ideas for solutions.”

As Lightfoot enters the final budget cycle of her current term, her track record on cultivating community engagement around the budget is mixed.

Her administration had initial success attracting resident input, but participation has waned. And while her budget office touts broad investments based on community feedback, some community organizations are angry that she has ignored their calls for specific solutions.

Lightfoot sounded perfectly comfortable with her administration’s approach to engagement when she spoke to the remaining crowd at the end of the forum. “Doing the people’s work is not easy. Sometimes they appreciate us, sometimes they do not,” she said.

In an email to the Weekly, a spokesperson for OBM said, “Initial feedback from participants and City leaders who participated in this year’s Forums indicates that the content and format was viewed as valuable and educational.”

The spokesperson added that “residents who attend[ed]…[were] able to meet fellow Chicagoans from different neighborhoods and learn from each other about their priorities and experiences…. This expands peoples’ viewpoint and allows them to better understand the separate sets of struggles we all face.”

Lightfoot will present her recommended 2023 budget to City Council in September or October. The council is expected to approve a budget by the end of 2022.

Correction, August 22, 2022: A previous version of this story misspelled Ransby-Sporn’s name. Their quotes were also updated to reflect support for a non-police response model. We regret the error.

Grant Schwab is a government bureaucrat turned journalist. He has a Master’s degree in public policy and previously worked as a state budget analyst in North Carolina. You can follow him on Twitter @GrantSchwab.