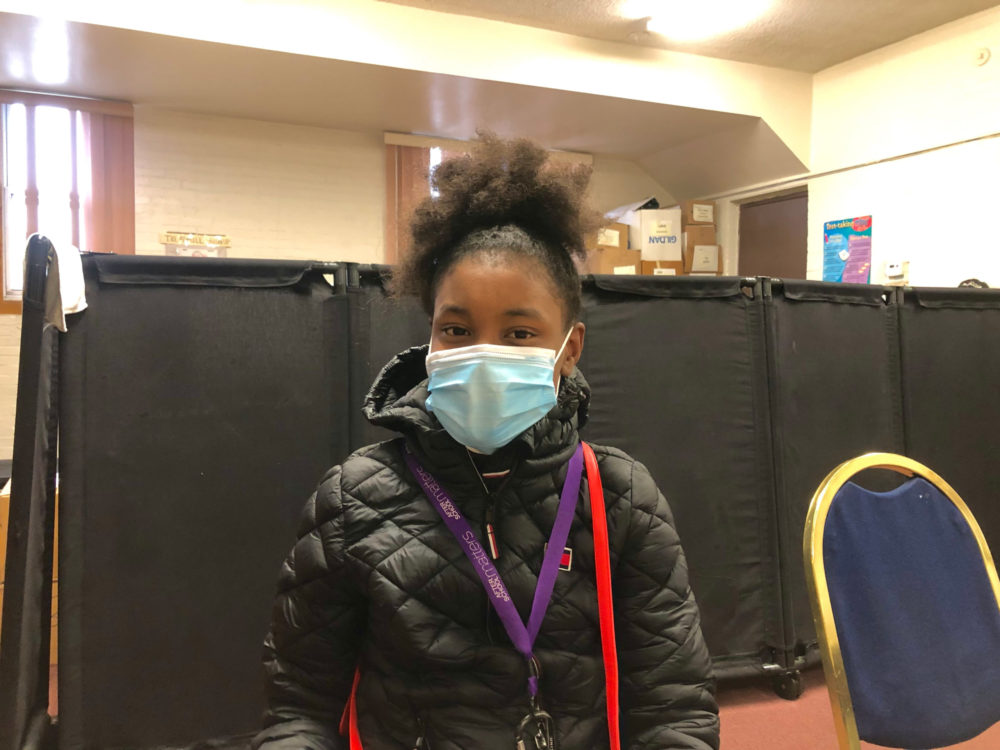

Myshayla Echols, a twelve-year-old Englewood resident, decided to get vaccinated in August for two reasons: First, “to protect myself,” and, second, her love of seafood. Although Echols was scared to get the shot, her father persuaded her with the promise of her favorite treat. “I was on the phone with my dad, and he said, ‘I’m gonna get you some seafood,’” Echols said.

After her feast of lobster tails and crayfish, the idea of a second shot wasn’t so bad. And once Echols got her shot, her twin sister was more eager to get it, too. “They’re talking to each other, having conversations with friends,” said Nashone Greer-Adams, founder of the nonprofit Something Good in Englewood.

Something Good in Englewood is one of many community organizations that are working to improve COVID-19 vaccination rates for children and youth and repair institutional and systemic health issues in particularly vulnerable parts of the city. These organizations are uniquely positioned and able to fill holes left by the City in some of the most underserved neighborhoods in Chicago.

Teens aged twelve to seventeen became eligible for the vaccine in May, and children ages five through eleven were approved for the Pfizer vaccine on October 29. By now, all minors can get vaccinated at select pharmacies, community clinics, City Colleges of Chicago, and hospitals in the city—but accessibility in the South Side has been a persistent challenge.

As of early November, twelve ZIP codes had vaccination rates below forty percent—all on the South or West Sides, according to data obtained by a public records request. In South Shore, just 32.78 percent of youths aged twelve to seventeen, or 1,101 teens, had received one dose.

Chicagoland Vaccine Partnership, a collaboration of more than 160 organizations, is leading efforts to vaccinate Chicagoans in these areas, as well as strengthen a severely disinvested public health system. It has provided funding to around sixty local organizations around Chicago through a fund of $1 million from local philanthropies to provide community-designed vaccination outreach efforts.

By investing in Black- and brown-led groups, the Vaccine Partnership believes that vaccination outreach efforts will be more effective and address the root causes of the vaccine disparity that has been widely reported. “This is not a quick fix to make sure we satisfy a dashboard,” said Max Clermont, the U.S. Public Health Accompaniment Unit’s senior project lead for Chicago. “This is really about building community capacity to respond not just with what is relevant, but respond to everything that plagues communities that have had a history of disinvestment.”

The Vaccine Partnership aims to empower residents by involving communities and hosting events like vaccination drives and youth programming. The collaborative works to mobilize community knowledge. “Your expertise in your community or your expertise doing community engagement, or around violence or working with seniors or parents and families… that is exactly the expertise we need,” Clermont said.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s Protect Chicago 77 Initiative also seeks to involve community organizations. The initiative has been an effort to vaccinate seventy-seven percent of the city’s population aged twelve and up by the end of the year.

Citywide, 75.3 percent of Chicagoans aged twelve and up have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, according to the city portal on November 4. However, these rates vary widely within the close to sixty different ZIP codes in Chicago.

The City hosts vaccine drives and strives to educate residents in underserved community areas, working with regional and community-based organizations already receiving funding through a separate City initiative, as well as health care providers, business partners, and faith leaders, a spokesperson told the Weekly.

Some residents needed other motivations to get the shot. According to organizers from Something Good in Englewood, incentives such as Six Flags tickets, provided by the State of Illinois, have proved especially successful with young people.

But some community leaders said they haven’t seen much City outreach in their neighborhoods. “We don’t see any City of Chicago presence in the South Side concerning vaccination,” said Justin Morgan, director of operations for Something Good in Englewood.

Although the vaccination initiative explicitly targets efforts in neighborhoods with lagging vaccination rates, it hasn’t exactly leveled the playing field. Vaccination rates are continuously increasing citywide, but some South Side neighborhoods still lag behind neighborhoods on the North Side.

Something Good in Englewood is one of the roughly sixty recipients of funds from the Vaccine Partnership. Englewood, in ZIP code 60621, recently had the second-lowest youth vaccination rate in the city, with just 30.03 percent of children twelve to seventeen fully inoculated with two shots.

Something Good in Englewood is a “one-stop shop” for an array of mental and physical health and finance services. The charity hosts monthly pop-up events, teaches community members financial literacy with partner Greenlight, offers job fairs, and provides onsite mental health services—all in addition to providing COVID-19 testing and vaccinations.

Morgan said making the vaccine as accessible as possible is very important, especially when appealing to young people. At one recent COVID-19 vaccination drive, Morgan said that the vaccination bus was two hours late. Many waiting for the bus to arrive eventually just walked off. “We persuaded a lot of our residents to get vaccinated and they were sitting there, and they were like, ‘I guess this is a sign we’re not gonna get vaccinated.’… it was absolutely terrible,” said Morgan.

Trust is a key element in the operations of these community organizations. Part of this trust is understanding that each individual has different needs and motivations. “We understand this community because we are of this community,” said Adams.

Something Good in Englewood also door-knocks and canvases for vaccination efforts. “We need more feet on the ground spreading the right information. There’s so much misinformation out here about the vaccine,” said Adams.

Melanely Cortez, nineteen, of Back of the Yards, got the vaccine after a family member in Mexico died of COVID-19. “I was scared at first,” she said, noting the side effects of the vaccine. However, now she feels glad she got it, despite worries of new variants.

Devonta Boston is the founder of TGI Movement, a nonprofit that creates an “oasis” for area youth. When working with teens, Boston said he tries to be relaxed in his approach toward the vaccine. “I try not to push it,” Boston said. “It’s there if you want it.”

The Oasis is a place for young people to “reclaim the hood.” The organization gives youth a space to showcase talents and nurture passions. Like Something Good in Englewood, TGI Movement brings the city-run vaccination bus to events. This has helped people get vaccinated, Boston said.

At a September back-to-school event, Boston said around ten people got vaccinated. “There’s so many reasons not to get it,” Boston said. “They need a reason to come…You gotta make it worth their while.”

Looking forward, as vaccines become available to even younger age groups, Clermont said Vaccine Partnership’s approach may need to change even more. “The strategies we employed for adults are not going to be the same for [children],” he said.

Some of the biggest challenges in vaccination efforts lie not in the vaccine or COVID-19, but in larger, more structural issues, organizers said. Community organizations in Chicago are tackling two pandemics as they strive to improve vaccination rates in South Side neighborhoods.

Gun violence and other structural disinvestment were issues in the community long before COVID-19. “We’ve been in a pandemic before there was a pandemic in Englewood,” said Morgan.

No matter the age group, changing who gets a seat at the table to address bigger-picture inequities in Chicago is key. “The real work is not going to be done in some braintrust operations center downtown, Clermont said. “It’s gonna be done on the local level.”

Josephine Stratman is a reporter and student at DePaul University. She has previously worked for the New York Daily News and City Bureau Documenters, and currently works at two campus publications. This is her first piece for the Weekly.