Although Lee Weiner just turned eighty-one on September 7, the cadence and vivacious storytelling of his memoir, Conspiracy to Riot, would have the reader believe he were still in his late twenties organizing in Cabrini-Green and Woodlawn. Weiner was a member of the famed Chicago Eight, a group of organizers who were targeted and tried for conspiracy in federal court for their role in the unforgettable demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention on Michigan Avenue. Beyond the trial, Weiner takes us through his political journey via his upbringing in South Shore, a fateful bus ride to New Orleans, and his later life as a legitimate political strategist on the Hill in D.C. The lessons from Weiner’s past hold true today, as he reminds us that resistance, more than anything, is critical in the everlasting fight for social and economic justice.

Weiner grew up in the buzzing industrial South Shore of the 1940s and 50s. His South Shore was Jewish and entrepreneurial, with both his mother and father nursing respective family businesses. From his mother (and dinner parties with her friends), Weiner learned the previous generation’s struggles as union organizers and Communist Party members in the early 20th century. From his father, a commercial paint business-owner with heavy ties to the mob-fitted Painter’s Union, he learned about Chicago’s machine politics and how organized crime exerted more influence than common citizens.

Larger lessons about the world came from Weiner’s experiences in high school. On one occasion, he took a bus to New Orleans, and when the bus crossed over the Tennessee line all of the Black passengers he’d been speaking with got up and moved to the back. Weiner remembers seething with anger and vowing to never be so powerless again. Upon returning to Chicago, he got a job at a gas station on 63rd and Woodlawn Ave., learning street lessons from his Black coworkers back when Woodlawn was the buzzing Black neighborhood that organizers of today lament over. Weiner’s proximity to different cultures—and the naked injustices he saw firsthand—took him from “the aspiring middle-class Jewish boy track” and set him on his own path.

Throughout the 1960s, Weiner was a community organizer by trade, working in various capacities for the city’s Welfare Office and with a local community group called The United Friends, or TUF, located in Old Town. With the TUF, he embarked on some of the same efforts that community organizers support today: welfare and tenant unions, legal aid clinics, co-op food buying clubs, and affordable housing development. More demonstratively, Weiner recalls occasions where TUF emptied rats and roaches onto streets near city offices or dumped trash by the storefronts of slum landlords— derisive forms of direct advocacy that led to their fair share of run-ins with the police. These episodes seemed to be the next phases in the long fight for the same basic rights and protections, and that was the lesson to be learned in Weiner’s eyes. He came to believe it would be “the young kids who sometimes came with their mothers to the meetings, or sometimes on our group visits to the welfare offices” who would carry the torch for the next generation.

1968 and 1969 were tumultuous years, filled with reactionary politics and insurgent movements. Rife with electoral politics, Antiwar sentiment grew along with mainstream media coverage of the abysmal Vietnam War. They were years of Black death, as two of the Civil Rights movement’s most prominent leaders, Martin Luther King Jr. and Fred Hampton, were assassinated. They were years of conspiracy, with the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy shaking up the American consciousness just a few short months prior to the Democratic National Convention. Most relevantly, 1968 was the year of the emergence of one of the 20th century’s most notorious “law and order” candidates: Richard M. Nixon. All of these events would set the tone for the demonstrations at the Convention, and the ensuing trial, like sirens in the background of the courtroom.

Though Weiner was a movement organizer and an active participant in the Convention protests, his point of view when recalling the events of the late sixties is almost like that of a spectator. This perspective is fortunate for the reader, as Weiner often seems like the most observant person involved in the action. When reading Weiner’s recollection of the demonstrations, which mostly took place on Michigan Ave. and in Grant Park, one is struck by the similarities between this imagery and the events we’ve witnessed on our own streets in recent years. There is the common instance of police charging crowds and trampling protesters, picking out individuals at random to beat with clubs. There were other instances of undercover cops blending into the crowd to overhear strategic discussions between marshals and subsequently stalking them—which is how Weiner was caught and indicted. Even heavy-handed language from Mayor Richard J. Daley was present, as he’d recently chastised the police superintendent for his passivity in dealing with the riots after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. His famous demand on that historic night: to “shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand, because they’re potential murderers, and shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting.” This was the backdrop, and for one of the first times ever, television cameras caught most of the chaos in real time, just like reporters today use social media to cover protests live. Although it was all a half century ago, these parallels have an uncanny resemblance.

The trial itself brought protesters to Federal Plaza every day, just as organizers convened in Federal Plaza for protests this summer. It also brought the group of defendants, which included co-founder of the Black Panther Party Bobby Seale, some amount of celebrity. Around the nation, university students and movement groups hosted the defendants to speak on their predicament, advocate for the antiwar agenda, and shed light on what they believed the trial was really about: “To use the courts against us, to intimidate and punish, and to define away or trivialize the political purposes and goals of the demonstrations in Chicago.” This, too, speaks to the mechanisms of the state today, where a clear and persistent demand to defund the police has been laughed off and trivialized by both local and national operatives.

What is true today was also true yesterday: there is ample room for accountability on the part of police forces and governments. The defendants and the general public saw the trial as a sham, an elaborate ruse by the federal government to publicly punish dissent—but what the government failed to take seriously is the fact that many people had seen what happened in Grant Park live and on camera, just like they were seeing the events of the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. There was nothing the government could do to sway public opinion since the truth had already been exposed, and fairer narratives were being formed; ones where “the police and government shared more of the responsibility for what happened due to their deliberate and illegitimate use of force to punish dissent.” The truth energized the movement, and the defendants drew nationwide support in what was just one event in the most eventful decade of the fight for civil liberties.

In his conclusion, Weiner tells us that “there is no more self-respecting, fulfilling life to try to lead” than one that is political. Though the work will drag us through the full spectrum of emotions, the wins, whether big or small, can be the most transcendent, joyous moments of our lives. The vigor and solidarity involved are all feelings that make the work infectious—and keep it ongoing. Conspiracy to Riot chronicles the moments from Lee Weiner’s life that forged him as someone willing to jump atop cars with a bullhorn, be a helping hand for families in Woodlawn and Cabrini-Green, fend off police officers to de-arrest comrades, and inspire a generation of movement organizers to continue fighting for a more equitable America. The stories in this memoir could serve as a mirror for some, and a starting point for others.

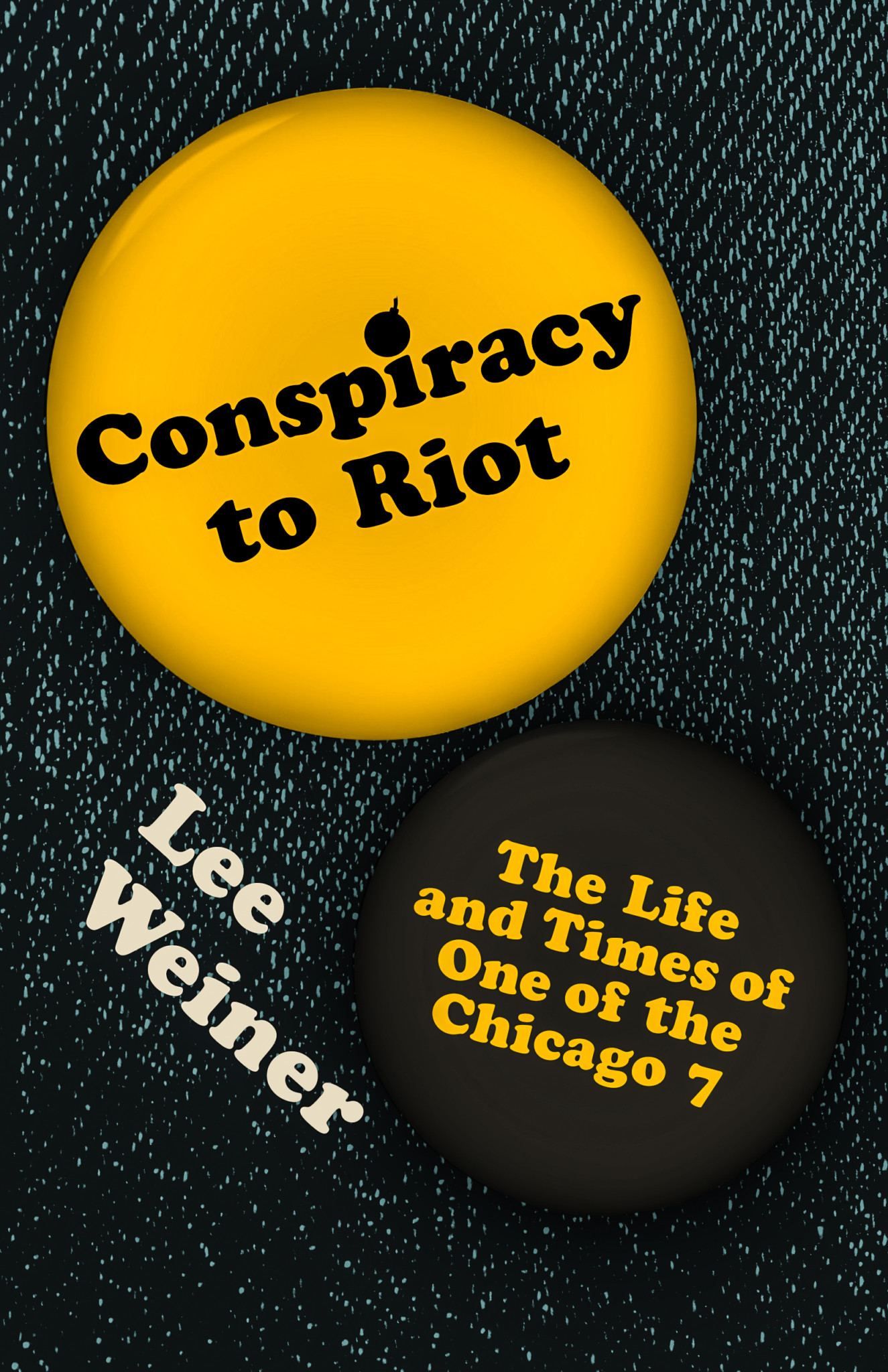

Lee Weiner, Conspiracy to Riot: The Life and Times of One of the Chicago 7. $26. Belt Publishing. 165 pages

Malik Jackson is a South Shore resident and recent graduate from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he majored in Urban Studies. He last wrote a review of Carlo Rotella’s The World Is Always Coming to an End for the Weekly.