The Cook County Criminal Courts system drastically failed to contain the spread of coronavirus or prevent the deaths of people in custody, according to a report released on September 16 by the Coalition to End Money Bond (CEMB)—and now the number of detainees is increasing.

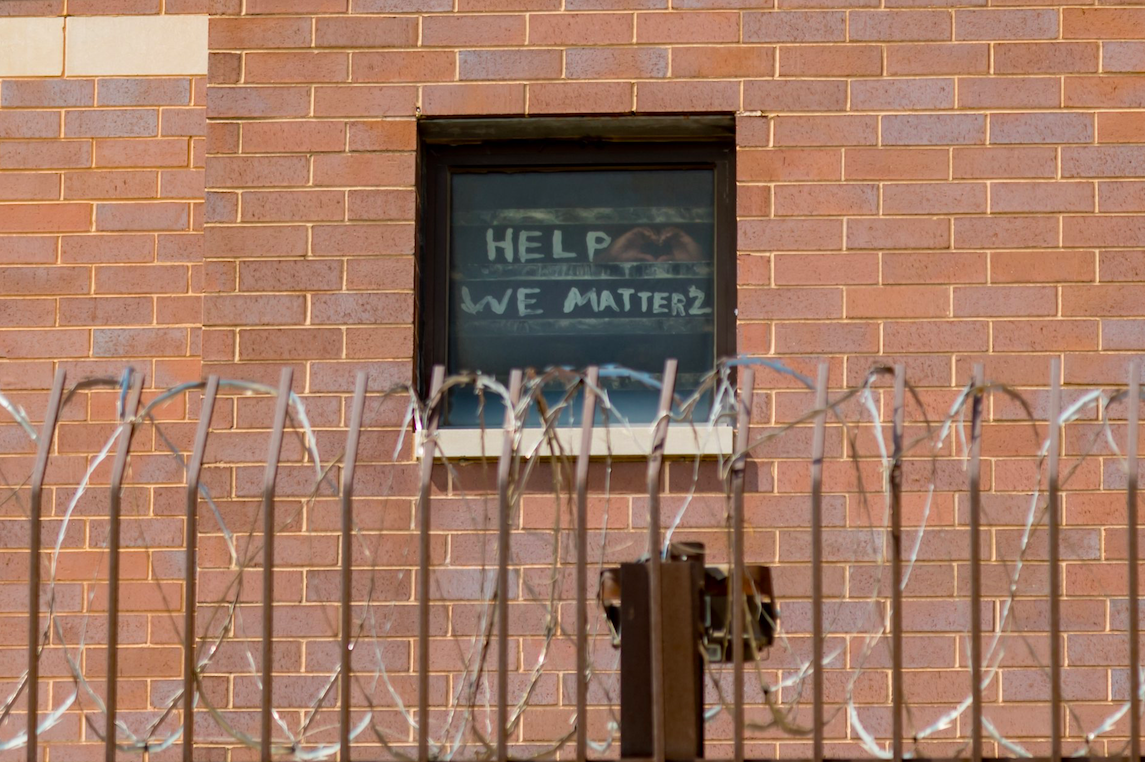

Hundreds of detainees and several guards have been infected with COVID-19 at Cook County Jail, and seven prisoners died from it between April 5 and May 4, 2020. In April, attorneys filed a class action lawsuit against Sheriff Tom Dart that called conditions at the jail a “rapidly escalating public health disaster.” Dart has defended the measures he took to curtail the spread of coronavirus and reduce the number of prisoners at the outbreak’s height.

According to the CEMB report, the number of people incarcerated in Cook County Jail is currently on track to return to pre-pandemic levels. That rebound follows a roughly twenty-seven percent reduction in detainees to a low of 4,031 people on May 9—which the report says disproportionately benefited white people. According to data the CEMB obtained from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office via a FOIA request, between March 9 and May 9 the number of white prisoners decreased by forty-two percent, compared to twenty-nine percent of Latinx prisoners and just twenty-seven percent of Black detainees.

Despite the initial reductions, by September 4 the number of people held at the jail had increased to 5,159 people, close to the level detained on March 17, three days before Governor Pritzker announced a statewide shutdown.

“Simply put, for the first time since 2015, the number of people under Cook County’s correctional control is moving in the wrong direction,” the report reads.

“I think the main takeaway [from the report] is that we really are not out of the woods yet, in terms of COVID-19 with the jail [and] in terms of the number of people who are in the jail who don’t need to be there,” said Sarah Staudt, a senior policy analyst and staff attorney at the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice who did much of the data analysis in the report.

The report outlines three main reasons that the number of people incarcerated at the jail has risen since May 2020: cases are remaining undisposed (that is, not ending in a guilty plea, trial, or dismissal) for months, judges are still setting unaffordable money bonds, and bond review hearings are not taking place.

Because of COVID-19, fewer defendants are getting a chance to proceed with their cases, according to the report. From 2017 to 2019, the Cook County Criminal Courts entered an average of 6,759 case dispositions between April 1 and June 30. This year during that same period, the Courts resolved only 463 cases.

“If we don’t move these cases, it’s not like they just go away,” Staudt said. “Eventually, we will decide as a community that this crisis is somehow over. And we’ll still have to deal with all these cases, and there will be a massive backlog.” All stakeholders in the system—including judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys—need to implement strategies to catch up, such as identifying and quickly resolving cases in which all parties have agreed to a guilty plea, she explained.

Cook County has also seen a growth in the use of electronic monitoring (EM) since the onset of the pandemic, according to the report. EM allows people to be away from the life-threatening conditions of the jail and get to a place where social distancing is possible. But the restrictions that come with EM often bring financial burdens and can cause medical-related predicaments as well: if someone on EM has an emergency and wishes to seek medical assistance, they will only be deemed as not violating the terms of their EM if they call an ambulance to get to the hospital. If someone on EM goes to the pharmacy, for example, they can be considered in violation of their EM and be sent back to jail.

“We really want to make sure that, whenever we get through this, whatever this is, that that expansion does not become a new normal, that we have people incarcerated in their homes across the county,” said Matt McLoughlin, director of programs at Chicago Community Bond Fund (CCBF), a coalition member.

Cook County Jail’s brief period of decarceration at the start of the pandemic, followed by a rebound in its population, mirrors the general trends of jail populations around the country. “Most [jails] were able to get their populations down pretty significantly between March and May,” said Wanda Bertram, a communications strategist at the Prison Policy Initiative. “But then you fast-forward to September, and almost all jails have seen their populations rise again.”

A spokesperson from the Sheriff’s office declined to comment on the report, and said the office has not had any input on who is held at the jail.

The report also highlights how community organizations have been working non-stop since early March to raise awareness about the dangers of COVID-19 in Cook County Jail and to implement decarceration measures.

The CEMB was formed in May 2016 with the goal of keeping people from being detained simply because they are unable to afford a monetary bond. It currently counts more than a dozen member organizations, including legal advocacy organizations such as the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice, and community-based groups like A Just Harvest and The People’s Lobby.

On March 13, more than one hundred advocacy, community, and legal organizations released an open letter calling for the decarceration of Cook County Jail in order to protect the health of all Cook County residents. On April 7, CEMB members and other individuals participated in a solidarity car caravan outside of Cook County Jail to call for the mass release of people in detention.

In May and June, the CEMB trained more than one hundred community volunteers who were recruited by Coalition members such as the Chicago Community Bond Fund, Southsiders Organized for Unity and Liberation, Community Renewal Society, The People’s Lobby, and A Just Harvest, according to McLoughlin. Those community members collectively attended and took notes on the more than 850 bond hearings that took place in Cook County’s courts over Zoom and were broadcast over YouTube from May 18 to June 6.

CCBF originally intended to organize a courtwatching initiative that would have taken a two-week “snapshot” of the court system, since court-watching is incredibly labor intensive, McLoughlin said. However, the support for the effort was so overwhelming that CCBF decided to continue the program.

Ultimately, CCBF halted the effort after uprisings in the wake of George Floyd’s death began in late May, as many volunteers were engaged in supporting the protests. McLoughlin also said “we know that the outside political climate impacts what happens in bond court every day,” and continuing the courtwatching effort during a politicized time was unlikely to have returned useful data.

The data that the court-watching effort collected reveals a few troubling trends. When judges set a bond requiring a money payment, the bond was unaffordable a majority of the time, according to the report. Volunteers witnessed 338 D-bonds, which require a person to pay ten percent of the total in order to be released, being set. Of these, 178—or fifty-three percent—were unaffordable. (Court watchers deemed a bond unaffordable when it was set at an amount a person appearing in bond court said they could not pay.)

Furthermore, Black people were disproportionately impacted by the court’s policies: eighty percent of the people who appeared in Central Bond Court while the court-watching effort was in session were Black.

According to data obtained from the Sheriff’s Office by Coalition members, of the nearly 3,000 people detained at the jail on August 31, about seventy-eight percent never had their bonds reviewed.

Asked what progress on the situation would look like to the Coalition, Staudt immediately brought up the necessity of reducing the number of people in jail on unaffordable money bonds.

“That is like the lowest-hanging of lowest-hanging fruit,” said Staudt. Chief Judge Timothy Evans, Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx, and Cook County Public Defender Amy Campanelli have all expressed support for the change. “This should be a no-brainer.”

In 2017, Evans issued General Order 18.8A, which mandates that anyone unable to post monetary bail must be given a bond review hearing no later than seven days from when the bond was originally set.

“As far as we know, that isn’t happening and even if it did restart recently, there are people who never got a seven-day review,” Staudt said.

“The size of somebody’s bank account should never determine whether or not they’re placed in a cage,” McLoughlin said. “And it most certainly should never determine whether or not somebody’s life is put at risk.”

He also pointed to the Pretrial Fairness Act, a proposed bill in the Illinois General Assembly sponsored by Senator Robert Peters and Representative Justin Slaughter that would not only end the use of money bail, but also increase courts’ transparency and accountability and enact a slew of common-sense pretrial reforms.

Bertram agreed that the pandemic-time elimination of bond review hearings in Cook County was not a welcome development.

“There’s no reason to eliminate steps that guarantee basic fairness,” Bertram said. She brought up California’s temporary zero dollar money bail policy for certain offenses during coronavirus as an example on the national stage that “could pave the way for permanent and beneficial policymaking.”

“This is a crisis that is not subsiding,” Bertram added. “There’s really no reason from a public health standpoint for courts and prosecutors and police to be letting up on the efforts that they made to keep [jail] populations down.”

Staudt concurred. “We have to get people out of jail before we are faced again with a crisis,” she said. “The last time people died, and I do not want to see our stakeholders wait for another person to die to realize this [is a] crisis.”

Lucia Geng is a student on leave from the University of Chicago who can be followed on Twitter @luciageng. This is her first piece for the Weekly.

People need to be let out of that hell whole as many as possible. The place is a death trap. Most have paid their time by waiting for a trial.