This story was produced by Injustice Watch, a nonprofit newsroom in Chicago that investigates issues of equity and justice in the Cook County court system. Sign up here to get their weekly newsletter.

Content warning: This story contains descriptions of people dying by suicide, homicide, and drug overdose.

The day before he died, Daniel Colon appeared in bond court via Zoom from a holding cell at 26th and California. The hearing was only a formality—his fate had already been decided—but as the judge was about to send him off, Colon spoke out of turn.

“Hold on, hold on, hold on,” he said.

“So the warrant from four years ago, I have to stay here for? Can you explain that?”

Colon ended up in bond court last February after Chicago police arrested him on the exit ramp off the Dan Ryan Expressway in Englewood where he often asked for spare change. The five officers who surrounded him that day said they were taking him in because of a warrant for missing court in 2018 for possessing five grams of heroin.

When Colon asked the cops why now, he got only cryptic answers. “Something has to be done now, all right? Nobody wanted this to happen,” the arresting officer told him, according to audio footage from the officers’ body-worn cameras.

The warning signs were already there. Colon’s wrists were so swollen, the handcuffs wouldn’t fit. Still, the cops took the twenty-eight-year-old to the 9th District police station in Bridgeport, where he spent the night in lockup, and then to the criminal courthouse the next day, where Cook County Judge David L. Kelly answered Colon’s questions almost as fast as he had asked them; the warrant was set at no bail and Colon was due back in court in four days “You’ll be able to address it with the judge at that time, sir,” Kelly said.

Colon never made it back to court.

After the hearing, Colon was taken to Cook County Jail, where he told the jail’s medical staff at intake that he was a daily heroin user and complained about cold sweats, diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach cramps—all symptoms of opioid withdrawal, which can quickly turn deadly.

Medical staff prescribed him a cocktail of seven medications and sent him to the jail’s highly touted detox housing.

Colon died less than twenty-four hours later.

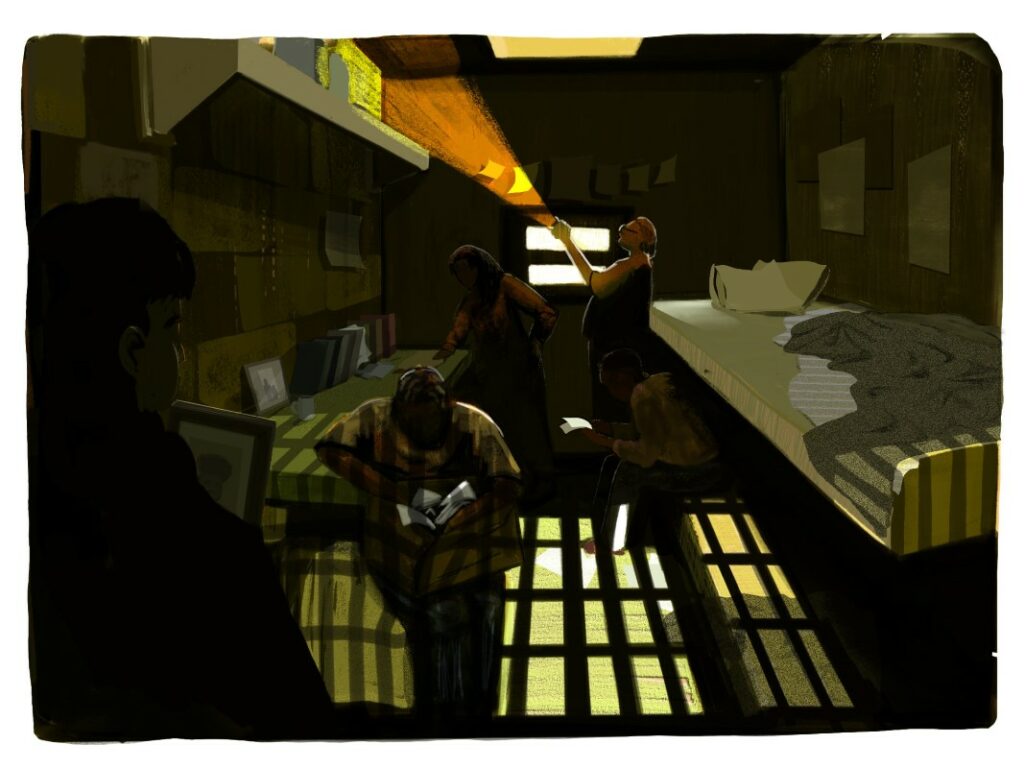

Surveillance footage reviewed by state police investigators shows Colon went to his detention pod’s shared bathroom at 12:18am after writhing in pain on his cot, and sat on the toilet for seven hours. Detainees reported hearing Colon in distress throughout the night.

Under state law, detainees are required to be monitored at least every thirty minutes. The officers on duty told investigators they checked on him five times during the night and he declined their offers for medical treatment, but surveillance footage showed no officers entered the bathroom between 3:30 and 6:45am.

Shortly after 7am, a guard enters the bathroom, and then walks out. Within seconds, Colon crawls out of the stall and ends up on his back facing a surveillance camera. No one noticed for thirty-five minutes, until another detainee alerted guards to Colon’s condition. It takes another four minutes for medical staff to arrive at the scene.

By then, it was too late. Colon was cold to the touch.

More than a year after his death, Colon’s family cried as they learned the details of his death for the first time from an Injustice Watch reporter.

“No one deserves to die like that,” said his younger sister, Jamie Colon. “I mean, they basically abandoned him! He was only there for a day!”

A yearlong Injustice Watch investigation into deaths at the Cook County Jail reveals the lack of supervision contributing to Colon’s death is not unique.

Eighteen people died while incarcerated at the jail in 2023, the most deaths at the jail since 2013, when the daily population was twice as high. It marked the jail’s highest mortality rate since at least 1995, according to an Injustice Watch analysis of public records and historical jail death figures compiled by University of Illinois researchers.

A review of thousands of pages of internal jail records, police investigations, and autopsy reports found inadequate supervision and medical care preceded at least half of those deaths, almost all of which have gone unpunished.

There was the twenty-six-year-old with an undiagnosed brain tumor whose repeated complaints about severe headaches were ignored; the twenty-eight-year-old whom officers failed to check on for more than an hour only to end up brutally murdered by his cellmate; and the thirty-three-year-old found hanging in his cell while the understaffed jail’s medical wing personnel failed to check on detainees every half-hour as required.

Sheriff Tom Dart—who’s overseen the jail for close to two decades—failed to properly inform state regulators and the deceased’s family members of the troubling circumstances behind the deaths in his custody, despite Illinois law requiring his office to provide them with those answers.

Dart declined to speak with Injustice Watch. Instead, he directed his communications staff to provide responses to questions sent over the past three months.

Dart’s top spokesperson acknowledged it was “not acceptable that staff failed to intervene after seeing Mr. Colon in the bathroom for hours” but declined to discuss specifics in his case and many others, citing ongoing internal investigations.

He defended Dart’s record of oversight and transparency, saying each death goes through several internal reviews and external probes conducted by state police and county prosecutors. When policy violations are identified, officers and other staff members are punished and reminded to follow the rules, Dart’s spokesperson said.

“No one is hiding anything, and to imply otherwise is disingenuous,” he said.

Dart’s spokesperson said the “primary driver” for the record spike in deaths was a sudden influx of paper laced with fentanyl and other drugs that was smuggled into the jail in the first half of last year.

Indeed, drug overdose was the cause of death for eight detainees in 2023, followed by six from natural causes (including Colon), three homicides, and one suicide, according to records from the Cook County medical examiner.

Deaths and overdoses at the jail plummeted after Dart severely restricted access to paper last April, going so far as to block defense attorneys from bringing paper into the jail. As of this week, there had been no deaths at the jail in 2024, his spokesperson said. The jail’s average daily population has also dropped significantly following the abolition of cash bail in Illinois.

But even in some overdose deaths, Injustice Watch found potential policy violations and lack of oversight that may have dangerously increased the jail’s reaction time to offer medical assistance, and advocates and experts say Injustice Watch’s findings point to longstanding problems at the jail that run deeper than drug-laced paper.

Inadequate supervision and medical care at the jail were at the heart of a 2010 court-ordered consent decree in which Dart was forced to accept federal monitoring after a scathing U.S. Department of Justice investigation found “unconstitutional living conditions” at the then-overcrowded jail. A federal judge lifted the consent decree in 2017 after the county hired hundreds of new officers, increased training, and installed thousands of surveillance cameras—the first time the jail was free from federal oversight in more than four decades, a point of pride in Dart’s tenure.

But the repeated instances of inadequate supervision Injustice Watch found in its review of last year’s deaths illustrate the need for renewed outside oversight of the jail, said Michele Deitch, a leading national expert on correctional oversight and director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin.

Deitch reviewed Injustice Watch’s findings and said Cook County officials should create an independent oversight body to permanently monitor the jail, investigate deaths in custody, catch issues before they become trends, and provide the public and the families of detainees with regular updates about what goes on inside.

“Deaths in custody go to the heart of whether or not we’re keeping people in jail safe,” Deitch said. Independent jail oversight bodies—which exist in cities including Los Angeles, Seattle, and New York City —are best suited to “hold the agency accountable when they’re not living up to our values, expectations, or constitutional requirements,” she said.

In response, Dart’s spokesperson said, “Civilian oversight is no panacea for preventing jail deaths.”

In a statement, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle said the eighteen deaths at the jail last year were “incredibly concerning,” but stopped short of calling for greater oversight.

Supervision issues reemerge in jail deaths

To compile this report, Injustice Watch obtained thousands of documents through dozens of public records requests to Dart’s office, the medical examiner, the Illinois Department of Corrections, and the Illinois State Police’s Public Integrity Task Force, which investigated fourteen of the eighteen deaths at the jail last year.

Obtaining even basic information like the names of those who died at the jail required a records request, as Dart doesn’t publish a list of people who die in his custody, unlike sheriffs in other large cities including Los Angeles and Phoenix. Dart’s office and other county agencies heavily redacted some of the records they provided and refused to produce other records altogether, including shift logs and surveillance footage of Colon’s final hours, saying releasing them would interfere with an ongoing investigation.

Injustice Watch compiled key information about each person who died at the jail—such as the unit where they died, the cause of death, the time of death, and how long they had been incarcerated—to determine if the staff’s response followed Dart’s internal policies and promises for reform outlined in the court-ordered consent decree of 2010.

What emerged from the review were many lapses.

Most notably, records showed Dart’s office is still using the controversial practice of having a single officer supervise two tiers on the same shift, known as “cross-watching.”

As part of the federal consent decree, Dart promised he would “work to eliminate the practice” after the Justice Department said it had led to “multiple preventable deaths.” But the jail’s former court-appointed monitor, Susan McCampbell, acknowledged Dart is no longer required to abide by the agreement. “No jurisdiction is required to keep policies/procedures/practices in place when the consent agreement is no longer in effect,” she wrote in an email.

Injustice Watch found cross-watching played a significant role in the death of Michael O’Connor last year.

The thirty-three-year-old was found hanging in his cell on Christmas more than an hour after he was last seen alive by one of only twenty-four officers assigned to supervise nearly 800 detainees diagnosed with physical and mental health issues, records show.

Jail staff had a difficult time finding enough officers to work on Christmas, Dart’s spokesperson said.

That explanation wasn’t enough for O’Connor’s mother. “They left my son to die, and no one was there to stop it,” Valentina O’Connor said.

Asked for records showing how often detainees were cross-watched last year, attorneys in Dart’s office said no one kept track of those figures—a lack of oversight in stark contrast to Dart's oft-proclaimed penchant for data.

But records show at least three other detainees aside from O’Connor died on days in which their tier was being cross-watched for at least one shift.

Dart’s spokesperson acknowledged cross-watching should be “avoided as much as possible” but defended its practice as both legal and common in “many correctional facilities around the country.”

Even when tiers were properly staffed, records show three deceased detainees were in need of medical assistance or were already dead for an hour or longer before officers realized it.

Besides Colon and O’Connor, twenty-eight-year-old Marvell Reasonover wasn’t checked for at least an hour before officers found him bludgeoned to death in the jail’s maximum security division last March by his cellmate, who records show had assaulted another detainee just days before.

Dart’s spokesperson said the sheriff’s office “understands not only the legal requirement to perform thirty-minute checks, but also the importance of these checks to protect the health and the safety of individuals in custody.”

According to the spokesperson, Dart’s jail supervisors brought disciplinary charges against nearly 100 officers last year for failing to perform their legally required thirty-minute checks.

Still, guards failed to perform their thirty-minute checks in 12 percent of shifts reviewed last year by the Jail and Detention Standards Unit of the Illinois Department of Corrections, which monitors all county jails statewide.

Dart’s spokesperson said those statistics showed an 88 percent compliance rate last year and also pointed to the jail’s state-of-the-art, 3,500-camera video surveillance system—operated by a team of full-time officers “watching live security feeds during overnight shifts”—as further proof of the jail’s adequate supervision.

But he also noted that live video monitoring ends at 5:30am and said the primary focus was on ensuring tier guards were performing the required thirty-minute checks.

“There is no current expectation that every single incident or development in a living unit be actively monitored via video in real time,” Dart’s spokesperson said.

None of the officers who were supposed to be supervising O’Connor, Reasonover, or Colon have yet to face disciplinary action in those cases, records show.

Union officials for Teamsters Local 700, which represents the more than 2,000 correctional officers who work at the jail, did not return messages seeking comment.

Injustice Watch has sued the Cook County medical examiner for the release of surveillance video related to Colon’s and Reasonover’s deaths under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act. Those cases are still pending in Cook County Circuit Court.

Detainees’ families left scrambling for answers

Injustice Watch found examples of inadequate medical care and delayed responses to medical emergencies in the lead up to at least four deaths at the jail in 2023.

Only the deceased’s next of kin is able to request and access those records. Injustice Watch helped two mothers navigate the bureaucratic process to obtain their sons’ medical records.

In one of those cases, records show Makavelle Sampson, twenty-fix, had complained about severe headaches days before he died of an overdose in September. An autopsy later found Sampson had a two-inch-thick brain tumor that went undetected in the six years he was incarcerated pre-trial at the jail. A county pathologist said the tumor was a significant contributing factor in his death.

Sampson’s mother said her son would complain about his headaches almost every time they talked on the phone. “I just kept telling him to put in requests for medical. … It hurts to know he wasn’t helped,” Nakisha Sampson said.

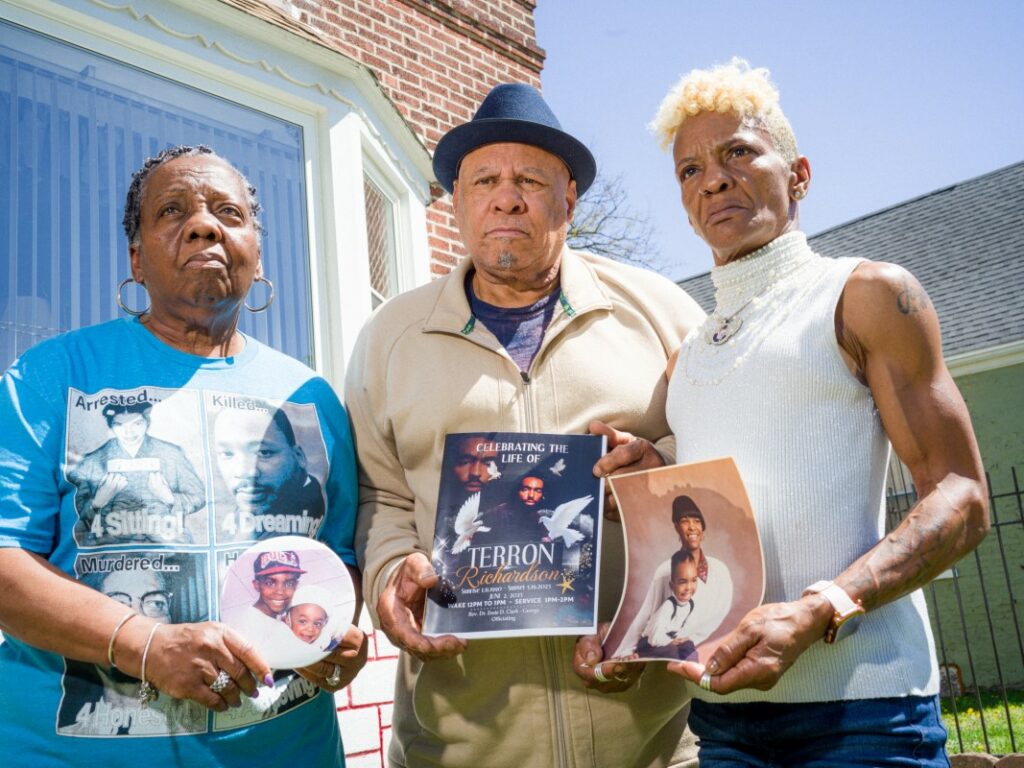

In the other case, records show Terron Richardson, thirty-three, had a history of refusing to take his prescribed medications before dying from a seizure in May 2023. However, on the day he died at the jail’s hospital, an officer tried to alert medical staff of his condition, but the medical staff member “simply walks away,” according to an internal investigation.

A spokesperson for Cermak Health Services, the division of Cook County Health that renders medical services in the jail, said the involved medical staff member no longer works for the county.

The jail’s medical director, Dr. Priscilla Ware, declined an interview request.

Three officers assigned to Richardson’s unit—Lt. Albert Stubenvoll and deputies Bruno F. Roti and Xavier Collier—faced disciplinary charges over his death, records show.

Investigators found Roti failed to appropriately respond to a medical emergency and falsified work-related records. He was recommended for termination, but retired before the case was completed, Dart’s spokesperson said.

Jail supervisors recommended a forty-five-day suspension for Stubenvoll and a 120-day suspension for Collier, but they haven’t served their suspensions yet, and neither have been relieved of their police powers in the meantime, Dart’s spokesperson said.

Richardson’s mother, Sharron Wesley, told Injustice Watch she was never informed about the internal investigation into her son’s death, which was closed three months ago.

“That was my baby, and they won’t tell me what the hell happened to him,” she said.

Lack of transparency with the families of the deceased is a common thread in all cases, Injustice Watch found.

The families of six detainees who died all said they were left with basic questions about what happened to their loved ones in Dart’s custody, despite a state law requiring the sheriff to appoint one of his staff members to serve as a liaison for each family and provide them with answers.

Nina Singleton, thirty-five, was visibly unwell in the mental health unit the night before she died from an overdose—so much so she needed help from three detainees to get to her bed, records show. She was dead by medical call the next morning.

Her mother, Nicole Brown, said a member of Dart’s office told her that her daughter had died but never followed up.

“I tried to contact him afterwards trying to see what was going on … and he apologized for no one getting back to me, but that was it,” she said.

Dart’s spokesperson acknowledged the sheriff’s office should be doing more to keep families informed. “Clearly, if family members feel that they are in the dark, there is more that we can do,” he said.

Jail deaths show oversight is faltering, expert says

Families of the deceased are not the only ones missing critical information about deaths under Dart’s watch.

State law requires sheriffs to file reports about deaths in their custody within thirty days to state regulators with basic information, including the decedent’s name, age, and “a brief description of causes, contributing factors and the circumstances surrounding the death.”

Injustice Watch obtained all of the reports submitted to the state’s Jail and Detention Standards Unit by Dart’s office since the start of his first term in December 2006. The reports have grown thinner in recent years, and failed to include required information about the circumstances behind the deaths in each of the eighteen cases from 2023.

In the section labeled “summary of specific details of occurrence” for the report about Colon’s death, for example, Dart’s office only reported his time of death, and failed to include any of the grisly details—details known to jail officials the day Colon died.

Omitting key details about detainees’ deaths defeats the purpose of the reports, which are meant to improve oversight and inform state officials and the public about conditions in the jail, said Jennifer Vollen-Katz, executive director of the John Howard Association of Illinois, an independent watchdog group that monitors the state’s prisons and, in the past, also monitored Cook County Jail.

“Reports that do not contain the statutorily required information thwart this effort and undermine efforts to keep people in custody safe,” Vollen-Katz said.

Dart’s staff provided no explanation for the inadequate reports to state officials, but said that any omissions were inadvertent and that his office is “incredibly transparent with stakeholders regarding deaths in custody.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for the Illinois Department of Corrections said members of the Jail and Detention Standards Unit are “actively reviewing” the incomplete death reports submitted by Dart’s office “and working with them to improve reporting.”

All deaths in custody also trigger an investigation with the sheriff’s own Office of Professional Review, which handles disciplinary cases against guards and other staff.

Aside from the three officers disciplined for Richardson’s death, only one other officer has received any punishment over deaths in custody last year so far, while half of the investigations remain open, even for deaths from nearly 500 days ago, records show.

Dart’s senior level staff also conducts internal reviews for each in-custody death to identify broader policy violations and issue recommendations.

In early April, when Injustice Watch requested copies of the internal probes, Dart’s staff had finished reviewing only six of the eighteen deaths from last year. His spokesperson said eight more have been completed since then.

The corrective changes stemming from the six reviews provided to Injustice Watch mostly involved reminding staff to follow basic protocols. For example, in the weeks and months after Colon died, guards were reminded via emails and at roll call to check the whole bathroom area during their thirty-minute security checks and to call for medical attention when detainees are in distress. The reminders included no mention of Colon or the lapses that preceded his death, records show.

Most of last year’s deaths were also investigated by the state police at the request of the sheriff’s office and forwarded to county prosecutors. But the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office has so far not filed criminal charges against anyone involved in the deaths, meaning the police investigations end up shelved and rarely see the light of day.

Ultimately, the investigations and death reviews are better at identifying individual policy violations than systemic issues that percolate from the top down, said Deitch, the correctional oversight expert at the University of Texas at Austin.

“If each and every case is looked at just on its own, then you’re never going to notice patterns,” she said.

When asked if he would welcome independent oversight of the jail, Dart’s spokesperson said his boss is already “held accountable daily by a host of government agencies, elected officials, and the citizens who elect him and other office holders.”

Yet none of those efforts have so far resulted in anyone being held accountable in Colon’s death. A year and a half later, his sister has low expectations.

“I don’t think they’ll do right by my brother.”

Dan Hinkel, David Jackson, and Eva Putnam contributed to this report.

This article first appeared on Injustice Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

It’s time for Dart to go.