On June 26, Chicago moved into Phase Four of reopening after initiating a shelter-in-place shutdown three months earlier to limit the spread of COVID-19. At its peak in late April, there were 1,400 new confirmed cases every day, but daily new cases now number around 200. Yet reopening to phase four, during which businesses are allowed to open—albeit with a number of regulations in place to reduce COVID-19 transmission—raises concerns that the city’s number of COVID-19 cases will again rapidly increase. To limit that possibility, Chicago announced in late May that it plans to begin widespread contact tracing in August.

Contact tracing is the process of identifying and isolating people who have been exposed to a disease to minimize their likelihood of spreading it. According to Dr. Allison Arwady, the Commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH), contact tracing has thus far been limited to patients who have been in congregational settings such as correctional facilities, nursing facilities, group homes, and homeless shelters. (Some hospitals and clinics, such as Howard Brown Health Center, have been doing independent contact tracing for their patients.) An additional 100 contact tracers will begin work in August to help track cases, and the hope is to have 600 contact tracers and resource coordinators employed within the next three months. The goal for CDPH is to have contact tracers capable of reaching 4,500 new exposed contacts every day. This has worked well in other countries and there is hope it will work in Chicago.

Contact tracing, also known as contact investigation, is the root of epidemiology, the process of monitoring and preventing diseases as they affect populations. The earliest record of it dates back to the 1500s after syphilis arrived in Europe, likely brought there from the Americas by Christopher Columbus’s crew members. Its use during the last century to contain diseases such as tuberculosis, STIs, measles—and more recently ebola and Zika— was similar to the contact tracing used to combat COVID-19. In all these diseases, patients who test positive are interviewed to ascertain if any one of their contacts may be at risk of infection. Then those contacts will be called and interviewed to determine if they need to be treated or quarantined to avoid further spread. These diseases all have different modes of transmission and the recommended protocols for case investigations is different for each, but the goal is the same: to prevent people who are at increased risk of having a disease from spreading it uncontrollably.

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

In countries that have successfully reduced their COVID-19 case numbers, contact tracing played a critical role. In New Zealand, authorities began contact tracing almost immediately. Their approach was thorough: any contacts a person who tested positive had made in the fourteen days before their test were also isolated. Additionally, New Zealand—whose population is twice the size of Chicago and is spread across an area 450 times as large—also restricted travel early on during their outbreak and achieved stricter lockdowns for non-essential businesses. As of July 20, New Zealand has had 1,200 cases and twenty-two deaths compared to Chicago’s 57,000 cases and 2,727 deaths. South Korea implemented a digital contact-tracing system it originally developed in response to the MERS outbreak of 2015 that uses a combination of smartphone GPS, credit card history, travel data, and medical records to inform citizens whether they need to self-quarantine. Amazingly, in a country of 50 million people that is roughly the size of Indiana, South Korea has only had 296 deaths.

The United States is unlikely to use digital tracing for its COVID-19 outbreak, given concerns regarding individual privacy and our lack of a centralized medical system. Several COVID-19 apps have been developed to help people keep track of their contacts, but without widespread adoption, they will have little effect. Both the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) have recommended contact tracing to slow the spread of COVID-19. But whether and how to implement contact tracing is left up to the states. Illinois has received $326 million through the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act to address COVID-19-related issues.

On June 11, the mayor’s office announced that it would be allocating $56 million from the CDC and the Illinois Department of Public Health to create 600 new public health jobs, including 480 contact tracing positions, for the next two years beginning in August. As implemented, Chicago would rely on a group of contact investigators comprised of public health officials and volunteers at the CDPH to call individuals who test positive for COVID-19 and identify anyone they had been within six feet of for at least fifteen minutes within forty-eight hours of developing symptoms (or within ten days of a positive test result for asymptomatic patients). Investigators share a list of potential contacts with other tracers who work on contacting and informing them that they were at risk, requesting they quarantine for fourteen days after the contact occurred, and telling them where to get tested if they have or develop symptoms.

Coordinating the effort to get widespread contact tracing completed throughout Cook County is the Chicago Cook Workforce Partnership (CCWP). On June 30, the City tasked the CCWP with hiring contact tracers through community organizations based in high economic hardship areas.

When Lori Lightfoot first announced the contact tracing initiative on May 26, she said that she’s excited to “expand health equity” in the city. “If we train up a legion of people from these same communities where there are health disparities, by virtue of the fact that they are involved in health care, their neighbors will know that they do this work,” Lightfoot said. “We hope that one of the residual benefits is … people understand they can be engaged with the health care system on a preventative basis and not just when they’re urgently ill.” She also noted that high-paying contact tracing jobs will get more people from these communities into public health roles even after the need for COVID-19 contact tracers diminishes.

CEO Karin Norington-Reaves said the CCWP has already started working with several community-based organizations to acquire contact tracers to hit the phones by August 15, and plans on having a total of 480 tracers working in September. Training will consist of a basic contact tracing course at Malcolm X College with refreshers every six weeks on updates for contact tracing best practices, as well as public health topics from Malcom X, UIC’s School of Public Health, and the Sinai Urban Health Institute. An additional 120 resource coordinator jobs will be managed by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC), which also holds contact tracing contracts in Delaware and Maryland. Resource coordinators will help connect affected contacts with resources and support in their communities to help with issues such as testing and self-quarantine.

However, while contact tracing is an important means of curtailing the spread of COVID-19—especially because people can spread the illness even when they have no symptoms—it won’t stop the pandemic on its own. Ayo Olagoke, a community health scientist at UIC’s School of Public Health, said “combating this pandemic requires integrated measures, including cohesive leadership, strong communication, physical distancing policies, and preventive measures like hygiene and wearing face masks. Contact tracing on its own will not be effective, it requires a joint effort.” She also noted that in order for contact tracing to be effective, Chicago needs to have easily accessible testing facilities. “The longer we delay testing, the more it weakens the effectiveness of contact tracing.”

In addition to Chicago’s order directing arriving travelers to self-quarantine for fourteen days, the creation of a larger contact-tracing network is part of a large effort to help keep Chicago’s COVID-19 cases down even as spikes are seen throughout the country. So, at the risk of occasionally hearing from unwanted telemarketers, make sure you pick up your phone in the coming months.

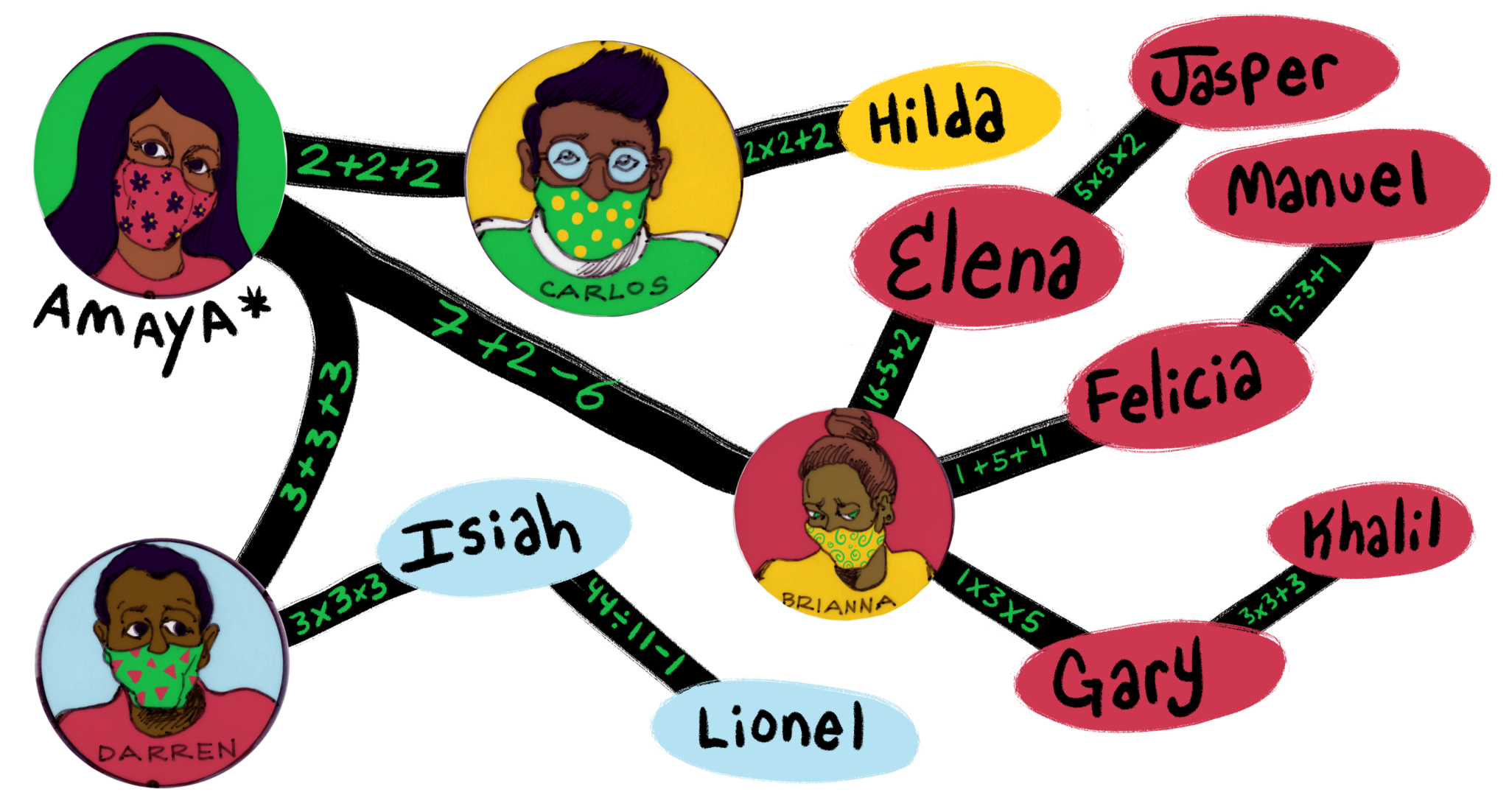

Want to test your contact-tracing skills? Try your hand at the Weekly’s contact-tracing game!

Elora Apantaku is a medical doctor and writer. This is her first piece for the Weekly.