And She Will is a brief, difficult volume. Only twenty-seven pages, it documents author Kwyn Townsend Riley’s “heal[ing] of self inflicted and reactionary wounds” after trauma. In early 2018, within weeks of each other, Riley gave birth to a stillborn son, her fiance ended their engagement, and she attempted suicide. Her second collection of poems explores her explosions of emotion in the time after these events, charting her grief and her journey toward self-compassion.

Known by the handle “Kwynology,” Riley coordinates a monthly open mic at The Breathing Room in Back of the Yards. She lives in Roseland, works as an organizer for BYP100, and has travelled internationally to speak and perform her spoken word poetry. Her first book And She Wrote was self-published in 2017.

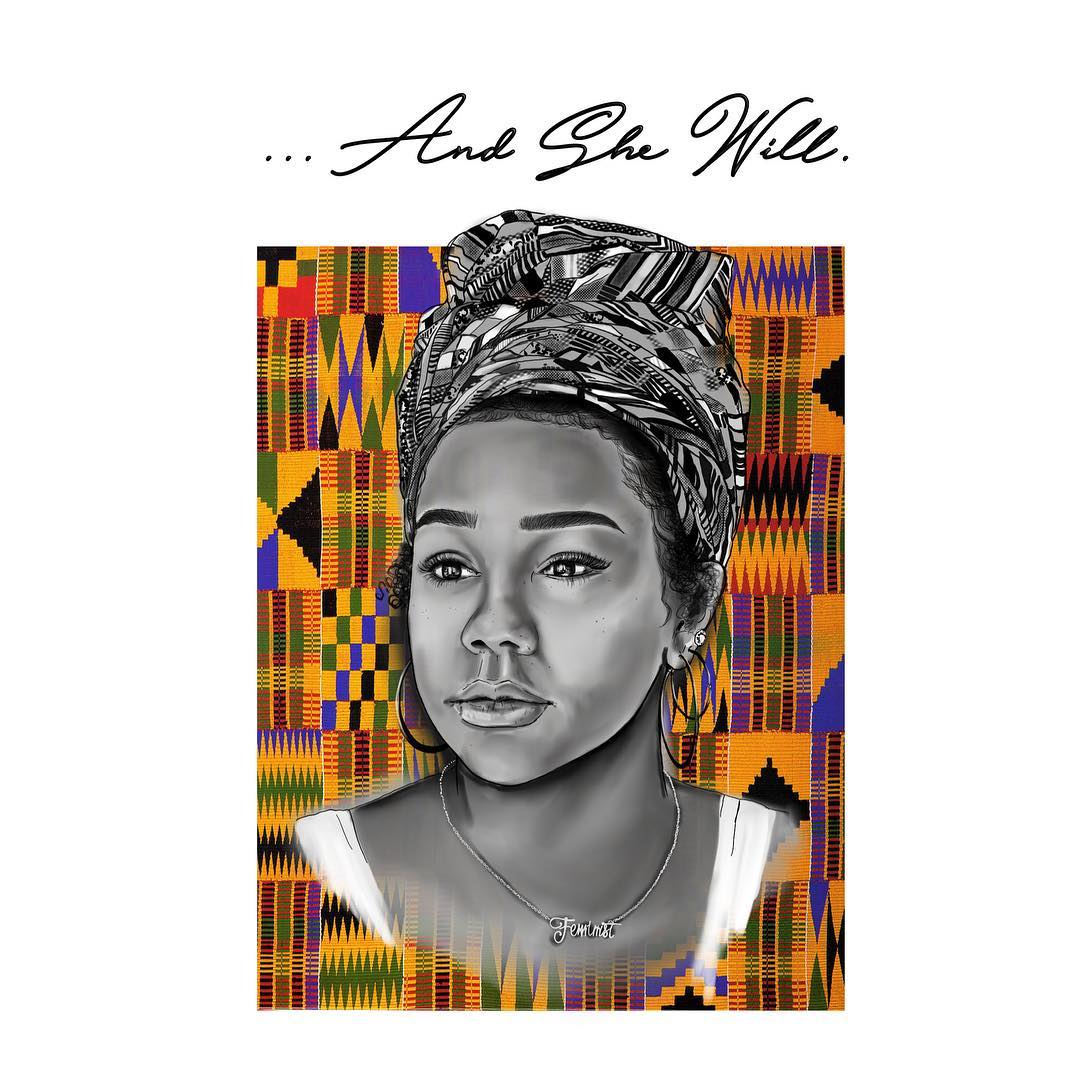

and She Will consists of thirty-two numbered poems, the majority of which occupy their own page, most accompanied by an illustration from Manda Pandie, a Chicago-based artist. Riley said that some of her poems are drawn from diary entries, and the confessional mode is evident throughout the collection. Riley doesn’t clip her words; her pain is bloody and she is full of rage. Many poems feel as though they are breathed out all at once, a single thought pulled out from a larger stream of consciousness. Capitalization wavers, punctuation fluctuates, and misspellings appear throughout the book. While initially distracting, these stylistic elements show Riley’s state of mind and transmit an emotional urgency—the words feel as if they are pouring out of Riley’s hand.

Riley searches for meaning in the death of her son, whom she often refers to as her “Sun,”—and many of the poems address God directly: begging for a reason, cursing her loss: “How could I trust a being/that destroyed my/precious someone?” She reflects on her religious upbringing, trying to reconcile it with her current reality. Toward the end of her poetry series, Riley reaches acceptance, admitting, “You are still good/God/I believe in you.”

Riley also writes about her ex-fiancé, mourning their relationship while acknowledging its imperfections (“You never needed me./I was just what you noticed that night./Our relationship was nothing but a night.”)—and, ambiguously, possible abuse (“my fiance cancelled the wedding./I grabbed a belt. The one he usually used”). As with other threads, she reaches acceptance, embracing how painful it is: “I think this was the best decision. And I know it hurt both of us.”

In several poems, Riley connects her own pain and journey toward healing with the treatment of Black women by society and their own families. Riley writes “blk womyn/will bend bone/Curl our fists/Move mountains with our tounge.” She proclaims “We are powerfully sensitive, and brilliantly weak.” Her spelling of “womyn” is purposeful; in an email she said it’s because “we don’t need a man.” Her use of “blk” is imbued with the same thought, as “blk people do not LACK,” she says. “Blk is more hard, more street and I fuck with it.”

As the book ends, Riley acknowledges she is still processing what has happened (“Sometimes the seduction of suicide whispers in my ears”). Yet, she finishes on a hopeful note, underscoring the role of self-expression in recovery. The last poem proclaims, “The Devil did not win today/For I wrote.”

Kwyn Riley, and She Wrote. $20. Self-published. 27 pages.

Jasmine Mithani is an editor at the Weekly. She most recently wrote a review of National Youth Poet Laureate Patricia Frazier’s debut book of poems.

This is a very intense read. I love Kwynology for sharing her journey.