Doing Time investigates the daily life of people navigating court and jail. We focus on Cook County, home to the country’s largest single-site jail, and the courts that order people’s release or jailing. Readers of this series will hear from insiders, formerly incarcerated people, loved ones, policy experts, and government actors to establish the forces that shape the everyday experience of doing time.

Some names have been changed to protect insiders.

You get hungry and you get desperate. You don’t care about nothing else.”

Patrick* has been incarcerated at Cook County Jail for more than a decade while awaiting trial. In that time, he has seen people go hungry and has gone hungry himself.

“I heard people tying their stomach with a line, like ripping a sheet and tying their stomach up. I done heard people putting toothpaste inside some tissue and then swallowing that,” Patrick said. “I done heard people just drinking a whole lot of water. I did that before a few times.”

At Cook County Jail, access to sufficient high quality food marks a central challenge for many incarcerated people, especially those who have been in the jail for years. Insiders have two options for food: eat the meals provided by the Cook County Department of Corrections (CCDOC) or buy food from the commissary. In interviews with the Weekly, insiders said that the food provided by CCDOC is frequently unappealing, low in nutritional value, and doesn’t keep them from going hungry, while commissary items are prohibitively expensive.

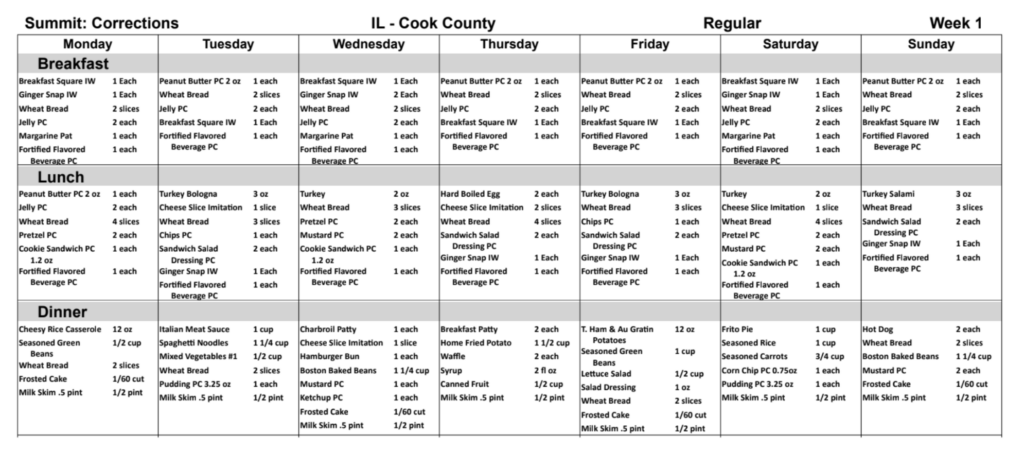

“Meals at CCDOC are designed by a dietician to ensure the required daily nutritional values are met,” reads one of just a few sentences in an Inmate Information Handbook that describe insiders’ rights and expectations regarding food. The ingredients for CCDOC meals are supplied by a vendor and then largely assembled and cooked by incarcerated kitchen workers. In addition to their standard menu, CCDOC has eleven menus it offers for detainees based on dietary restrictions, from halal to vegetarian to gluten-free.

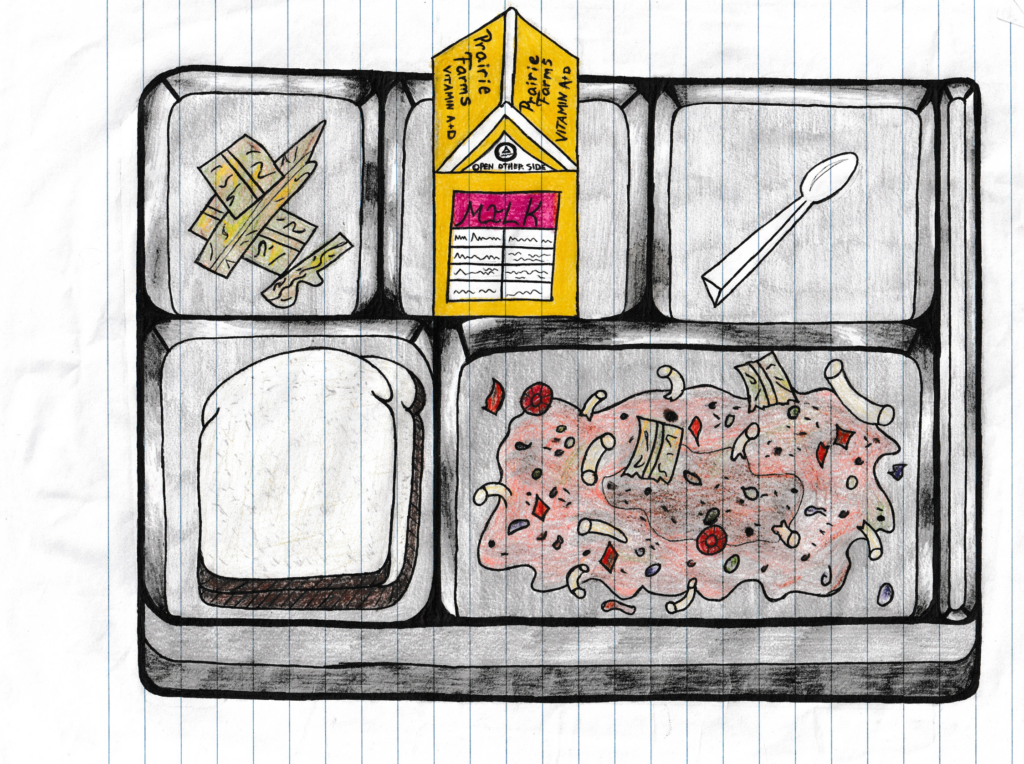

“They give us a whole lot of bread. We get like, twelve slices of bread a day,” said Charles*, who’s been incarcerated since 2019. “A slop at night. Sometimes we get lucky and get a hamburger patty.”

A sample CCDOC menu from November 2024, obtained by the Weekly via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, illustrates Charles’ point. Across the week’s twenty-one meals, split across breakfast, lunch, and dinner each day, there are almost no servings of fresh fruit and vegetables. The Weekly estimates that almost a fourth of the calories come from wheat bread alone.

According to CCDOC’s vendor contract, the daily calorie counts of their provided meals fall between 2,300 and 2,500. Recommended calorie intake depends on the person, but the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Dietary Guidelines for Americans notes that nineteen-to thirty-year-old men, who make up a majority of the jail’s population, need 2,400–3,000 calories per day.

Calories only tell part of the story. Across the week, insiders got around eight cups of vegetables or fruit, but less than four of those cups have the potential to be fresh fruit or vegetables. The USDA recommends at least thirty-five cups of fresh fruits and vegetables every week.

Dr. Sera Young is an applied nutritional anthropologist who studies undernutrition in global, low-resource environments. When looking at the menu, she described being “particularly concerned about fiber and just the calorie density itself. And it’s not counterbalanced by the possibility of physical exertion, which has got to be leading only to more feelings of frustration and violence.”

People with money sent by family and friends have a second option: the commissary. Some supplement or entirely replace their meals with commissary items.

Both because commissary items are expensive and commissary spending is restricted, it can be impractical for many incarcerated people to adequately supplement their diet. Based on the commissary list from 2023 (the most recent year audited by the Cook County Inspector General), items like a pouch of chicken and pouch of chili cost $6.49 and $4.39, respectively.

“What they’ll do is they’ll make the food real nasty, and then they’ll make the price so high on the commissary,” said Anthony*, who has been incarcerated pretrial for fourteen years. He also noted that insiders cannot spend more than $100 in commissary in a week. “So I order ten bags of chips, […] give two, three of them away. That’s $20. You only get to spend 100 bucks, give or take. Now, if you thought you were gonna buy meals to make, good luck with that.”

In an email, a Cook County Sheriff’s Office (CCSO) spokesperson wrote that the current weekly limit on commissary spending is $125, and is in place to prevent food hoarding and extortion.

Responsibility for the choice and quality of food served at the Jail falls under the CCSO, which administers CCDOC and the preparation and distribution of the food, and the Cook County Board of Commissioners, which allocates the budget and approves contracts with suppliers.

Since 2020, the County has contracted with CBM Premier–Summit Food Service Joint Venture, a South Dakota company that provides food for correctional facilities across the country. Summit has been subject to numerous complaints across the country, including insufficient portions and lack of fresh produce. The seventeen-member County Board approved a three-year contract with the company in 2022 for nearly $42.7 million. In May of this year, the Board voted to extend the contract by one year for $13.6 million, to a total of $56.3 million. In an email, a CCSO spokesperson wrote that just under $45 million of that had been spent by October 2025.

Warren*, who spent time at the jail before and after 2020, said the food used to be better. “They used to give us a little honey bun on the breakfast trays. They used to give us danishes, pop tarts, stuff like that,” Warren said. “They really hustling us.”

Summit Food Service LLC is the vendor for commissary and sells directly to insiders. According to a 2017 press release, Summit, which is part of catering business Elior Group, acquired CBM in 2017, though the CCSO spokesperson wrote the food and commissary contracts were with separate entities. Summit did not respond to questions.

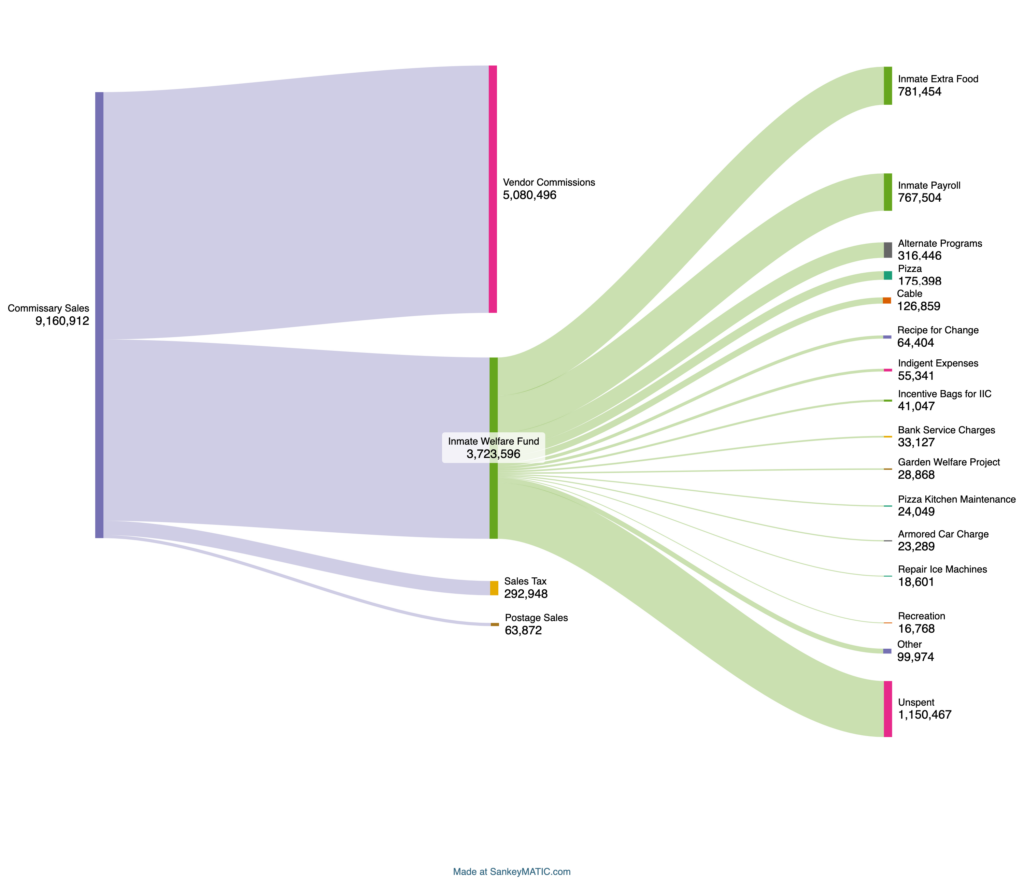

The County tacks on a commission of between 41-44 percent to each commissary item in order to generate revenue that goes into an ‘Inmate Welfare Fund,’ which covers resources ranging from food service repairs to sign language interpretation. From December 2022 to November 2023, the Jail made $9.1 million in commissary sales, of which over $5 million went to Summit and $3.7 million went to the fund. Of that, only $2.6 million was spent that fiscal year.

When the commissary vendor contract was put to a vote by the Board of Commissioners in June 2020, Commissioner Kevin Morrison (15th District) noted that while he is “never opposed to any revenue generating items that come before this board,” he pointed out that it’s difficult for incarcerated people to generate the income to pay for commissary and asked whether the county had considered “for the sale of these items to just be at wholesale instead of the county generating revenue off these items.” In response, Jane Gubser, executive director of programs at the CCSO, called commissary a “privilege” that enables incarcerated people to enact their “preferences,” naming food and reading glasses as examples.

Though lack of access to quality food can be difficult regardless of time spent inside, people incarcerated for multiple years speak to the diet wearing on them over time. Vincent* has been incarcerated since February of 2024 and spoke to health concerns he has about the diet. “For breakfast today, we got two slices of the bread. There was an old butter packet in it, and one little packet of peanut butter and two little packets of jelly,” he said. “If you don’t have sugar diabetes, and you stay here, you might have sugar diabetes, because everything is sugar, sugar, sugar. We don’t get no fruits and vegetables.”

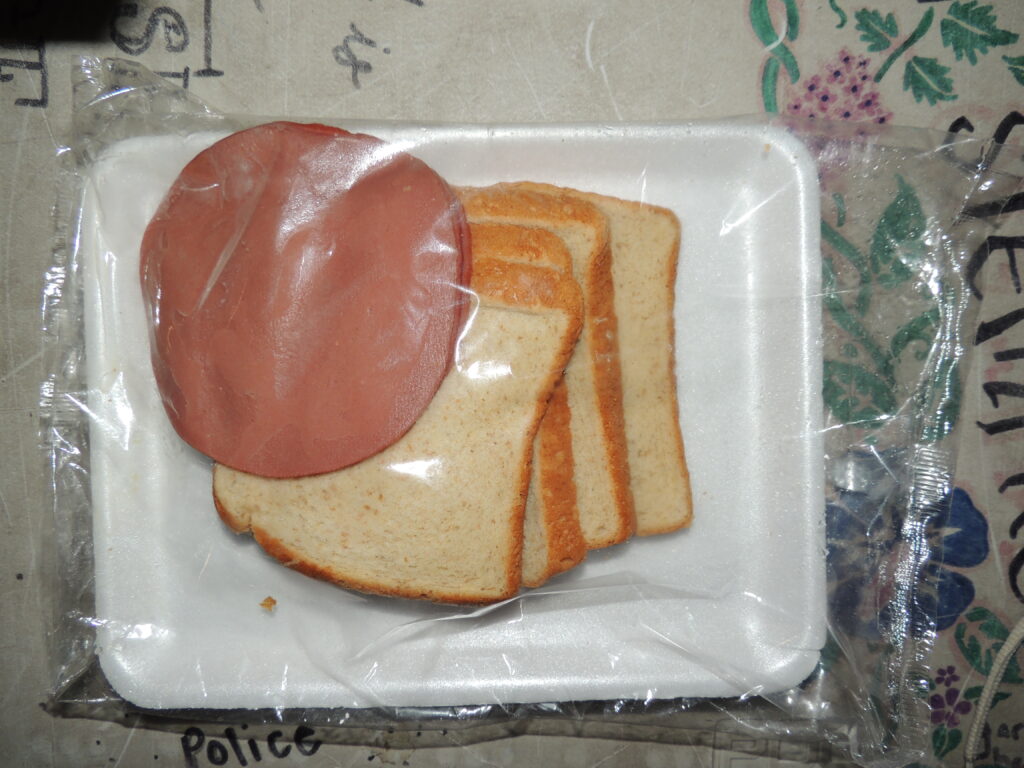

Beyond the nutritional issues with the CCDOC provided meals, insiders describe the food quality itself being poor. When asked the texture of the lunch meat served up to five times per week, Anthony answered simply: “Pig ears.”

Vincent explained that people inside find ways to make the food more edible. A person he shared a cell with hung the lunch meat in his cell, “and in two days, it turned into what looks like beef jerky.”

“People get creative though. They make it happen,” Patrick said. “They find a way to make it taste better and put it together, yes, and wolf it down as best as possible.”

As insiders struggle with the quality and nutritional value of the food, some of them go hungry—from not wanting to eat the food, or even despite eating it. Food insecurity can lead to tensions and conflict in the jail.

“They start stealing. Start stealing, start robbing people and shit. Tying people up and shit,” Patrick said.

“A two-year-old can eat [the tray] by itself and still be hungry,” Warren said. “So that resolves us to go eat our commissary. With other people who ain’t got that, they go in the garbage and stuff like that.” When he sees people resorting to the garbage, “I’ll just tell them, like, you ain’t got to do that. Man, you can have my tray.”

Harley Pomper is a PhD student in social work at the University of Chicago. They organize across jail walls to report on carceral injustices and political repression.