I opened Anayansi Ricketts’s Zen Garden: Transformations on a frigid January day, when the wind chill pushed the temperature to the single digits. But as I dove into the poetry collection, I was quickly transported from the frozen asphalt outside my apartment to a sunnier Chicago, surrounded by colorful flora and the smell of fresh mulch.

An artist and environmentalist, Ricketts is the founder of Urban Echo, which she describes as “an environmental consulting, design and art movement working to connect people to their righteous creative selves.” She also teaches art workshops at places like the Chicago Public Library and the Silver Room in Hyde Park.

Recently, she purchased a vacant lot in South Shore and began the work of transforming it into a garden. She’s christened it South Shore Botanical, and plans to seed it with native Chicago vegetation. “I bought the lot because I wanted to bring some beauty into the world and to teach people about native plants and how they can be used,” Ricketts said in an email.

Released in 2019, the self-published book is a record of nature and neighbors, and was included recently in an exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art titled “Nature and Social Justice in Twenty-First Century Cities.” “It chronicles transformation and growth, and how people can come together informally to create change,”Ricketts wrote in a statement accompanying the exhibit. “It is also a showing of positivity on the South Side. There is so much good happening here, and it is so overlooked.”

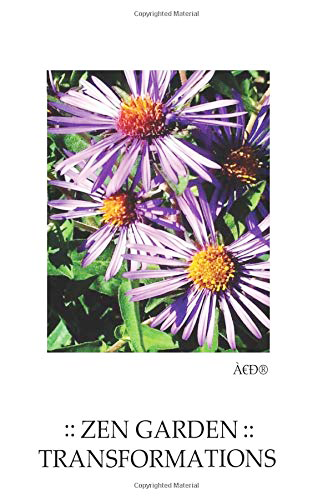

Zen Garden: Transformations chronicles Ricketts’s conversations with neighbors and passersby while she tends to the garden. Her observations of behavior are hopeful, alternating between contemplation and humor. Each poem is a few lines on the page, blank verse, paired with a photograph of the garden taken by Ricketts. The photographs, while not printed at the highest quality, are lush and dripping with rich color; flipping through the pages, the eye is instantly drawn to bright oranges and purples. There are also photographs of walls and cracked concrete, inviting the reader to see the beauty in these images too.

The poems aren’t organized in an obvious order. The book opens with Ricketts watching “young, black boys” play in the garden and progresses to a poem documenting the moment when she bought the lot (“the land turned over to a neighbor/as a way towards betterment”). Time is fluid; the poems are a diary of the seasons, equally noting days “too hot for man or beast or plant” and when “winds that chill blast away all evidence of summer.” Ricketts makes special note of the creatures living in the garden—my favorite poem references “two butterflies making whoopee”—acknowledging both the disruption her gardening makes and the new homes it provides.

Nearly all of the poems are written in the first person, sharing Ricketts’s conversations and inner monologues while she pulls weeds and repurposes found cardboard as mulch. The care she feels for the garden flows through the page, when she “had to use my superpowers to stop/a litter bug” and “my special brand of crazy tells me:/it makes perfect sense to mow a double lot/with a push mower.” Her voice is realistic, unafraid to talk about the difficulties of creating the garden, but always full of wonder and hope.

I have a black thumb, and these poems made me want to run outside and dig my fingers in some dirt. My daily interactions with nature are mostly limited to looking at the currently barren trees out my window, and I find myself yearning for a deeper connection. Ricketts’s writing conjures images of both my childhood home and a recent bike ride through Ping Tom Park, and inspires me to explore more of the city in search of the small beauties she so carefully describes.

At the end of the book, Ricketts thanks “everyone who has helped bring light into/darkness,” including readers who have donated their money or labor to the garden. (Proceeds from book sales directly fund the garden, with $630 having been raised to date.) The book’s penultimate image is a self-portrait of Ricketts’s shadow, the only glimpse we see of her in these photos.

Anayansi Ricketts. Zen Garden: Transformations. Self-published, 2019. Available on Amazon.com.

Jasmine Mithani is an editor at the Weekly.